- Click here to see the entire list.

- Certain selections and commentary below (functions best on desktop/tablet, due to length).

- Categories include:

Introduction

Chicago is an incredible place – one of the finest cities in the country. Though, like many current and former residents, my feelings are often up and down. The kind and generous people, awe-inspiring architecture, relative affordability, incredible cultural scene, historic sites, and amazing restaurants are tempered by political corruption, escalating violence, and institutional shortcomings city, county, and state-wide.

But Chicago is the first major city I visited on my own, terrified of the aggressive drivers and densely packed sidewalks. I married my wife in a civil ceremony at the garish Thomson Center before we both went to work for the day. And it was at the Chicago Cultural Center that I attended my inaugural map fair, exposed for the first time to the wondrous world of antique maps. There was no question that the city should be the focus of my first catalog; itself an experiment that I hope to learn from and build upon in the future.

I’ve amassed nearly 300 items in all, spread across nine different categories. Clicking on each title header will take you to a separate page with its respective material. Selected highlights are provided, directly linked to the product page. All items are offered subject to prior sale. Many thanks to Haywood, my family, and my mentors, George and Mary Ritzlin, for their invaluable help and support. Please drop me a line if you have any questions or if you find factual inaccuracies in the descriptions – they are bound to occur.

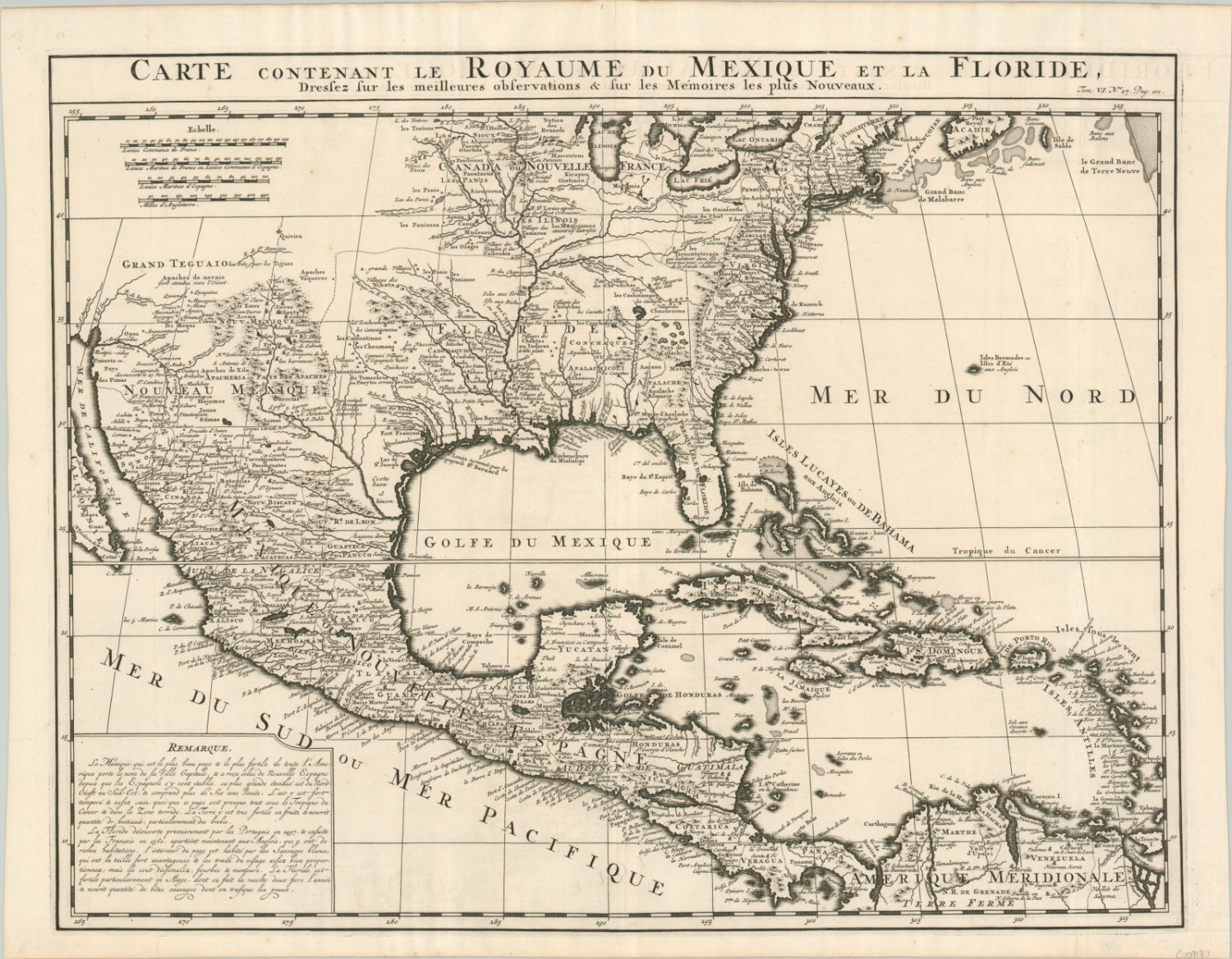

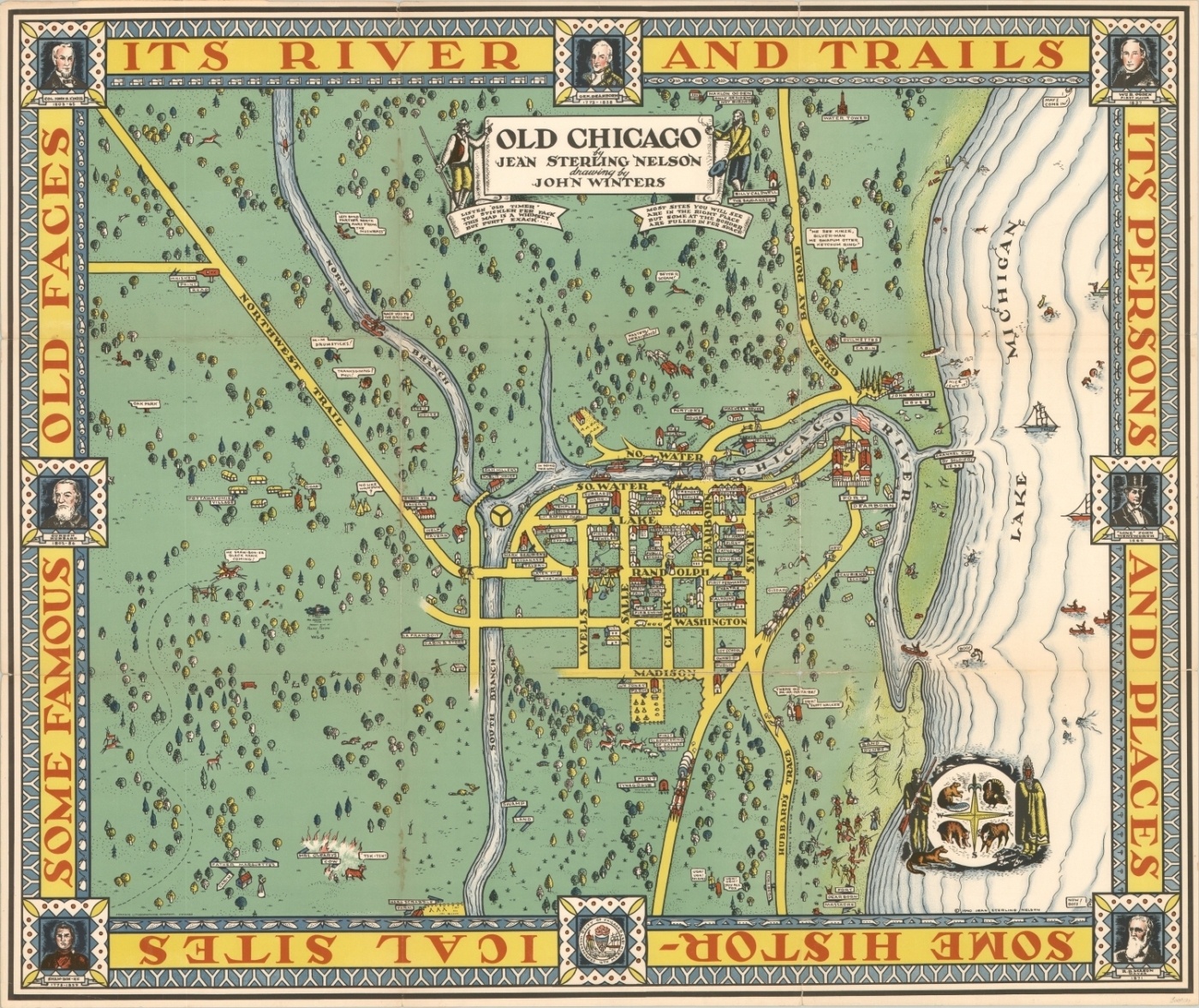

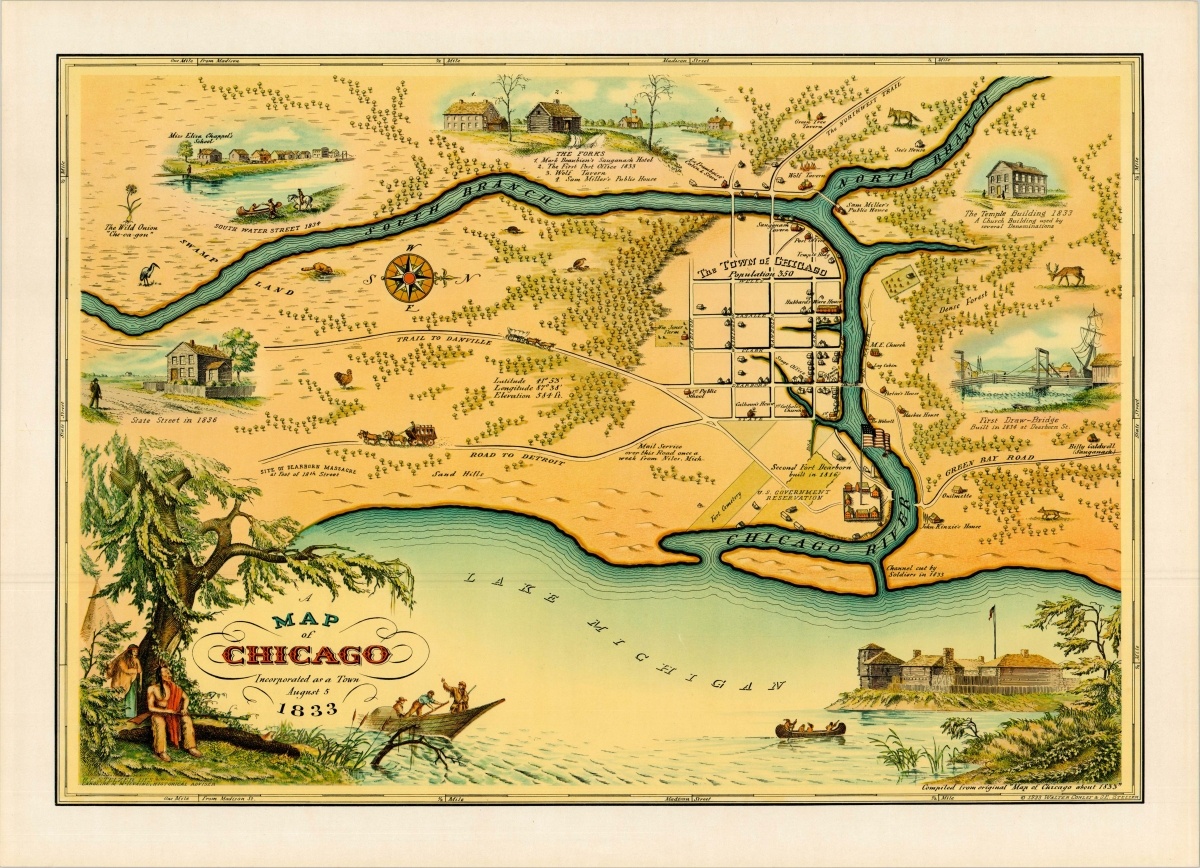

ThE Early Days

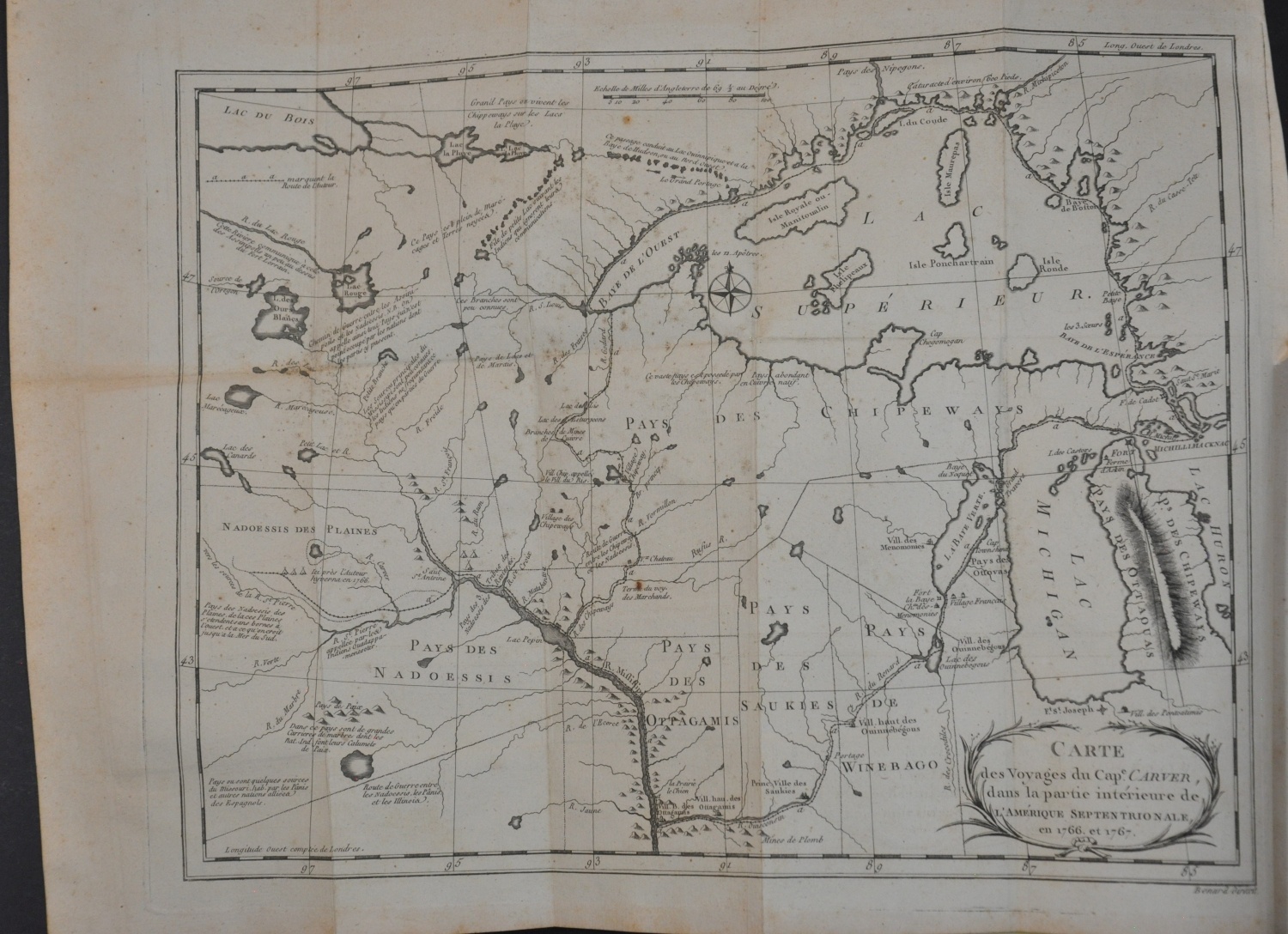

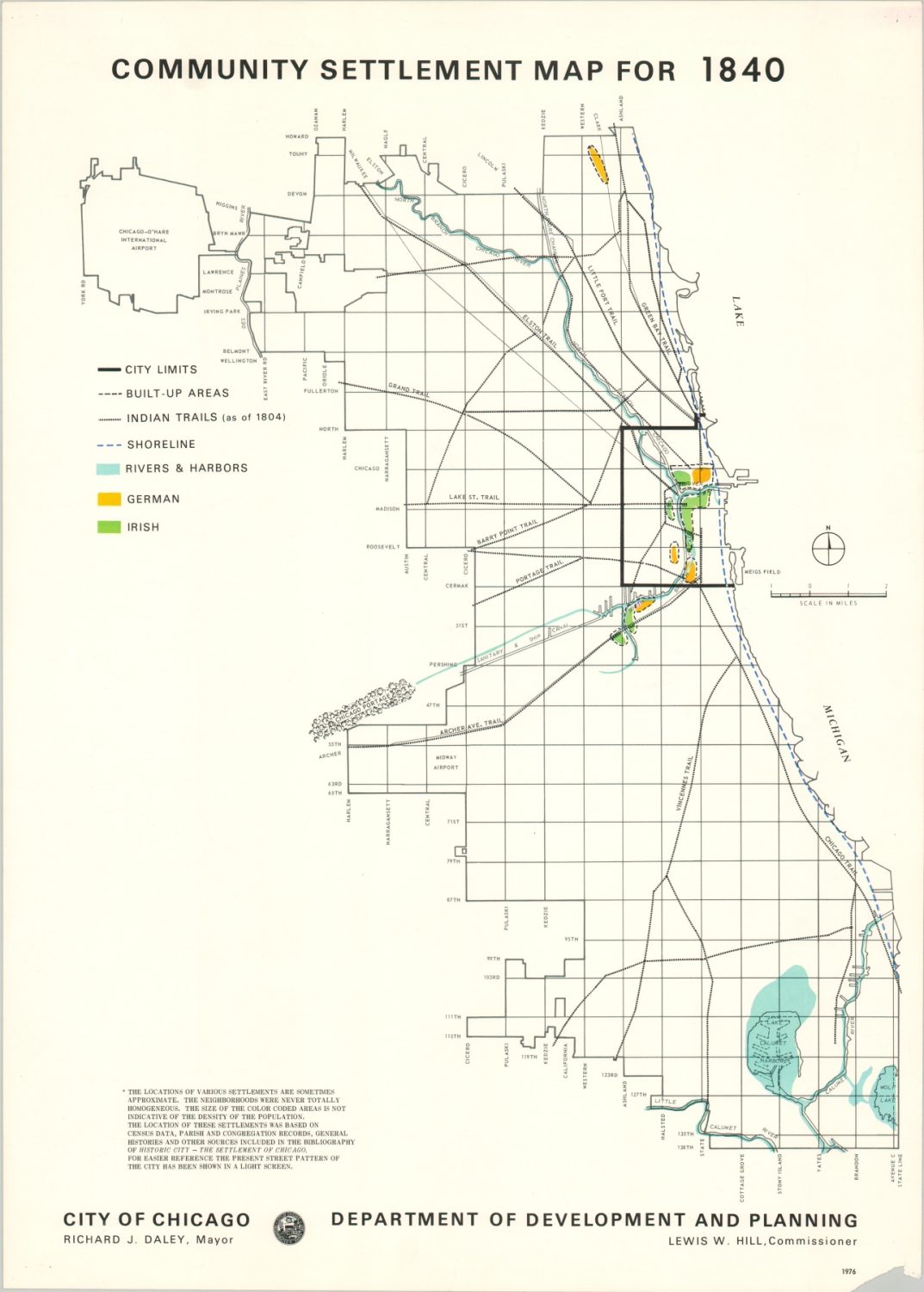

Though capturing their impact in cartographic form can be difficult, indigenous communities are at the heart of early Chicago. Native American trails and temporary tribal meeting grounds along the river formed a framework outline of the city long before the earliest European settlers trod on the native prairie grasses. Trade between native people and early explorers (Marquette, Joliet, La Salle, etc.) resulted in an exchange of goods, ideas, and geographic information that would have a powerful impact on both communities. It is from the Algonquin language that Chicago gets its name – likely originating from the word for a smelly plant, wild onion or garlic, that lined the banks of the river.

Five separate treaties effectively forced out the thousands of Native Americans that lived in the region that would become Chicago and its suburbs. The first, the Treaty of Grenville (1795), included the mouth of the Chicago River and the portage to the Des Plaines River. These sites were well beyond the scope of European control at the time but their inclusion in the peace document represented an early recognition of their strategic significance. Subsequent agreements relevant to the region were coerced from local tribes in 18““16, 1821, 1829, and 1833 – the year Chicago was incorporated as a town.

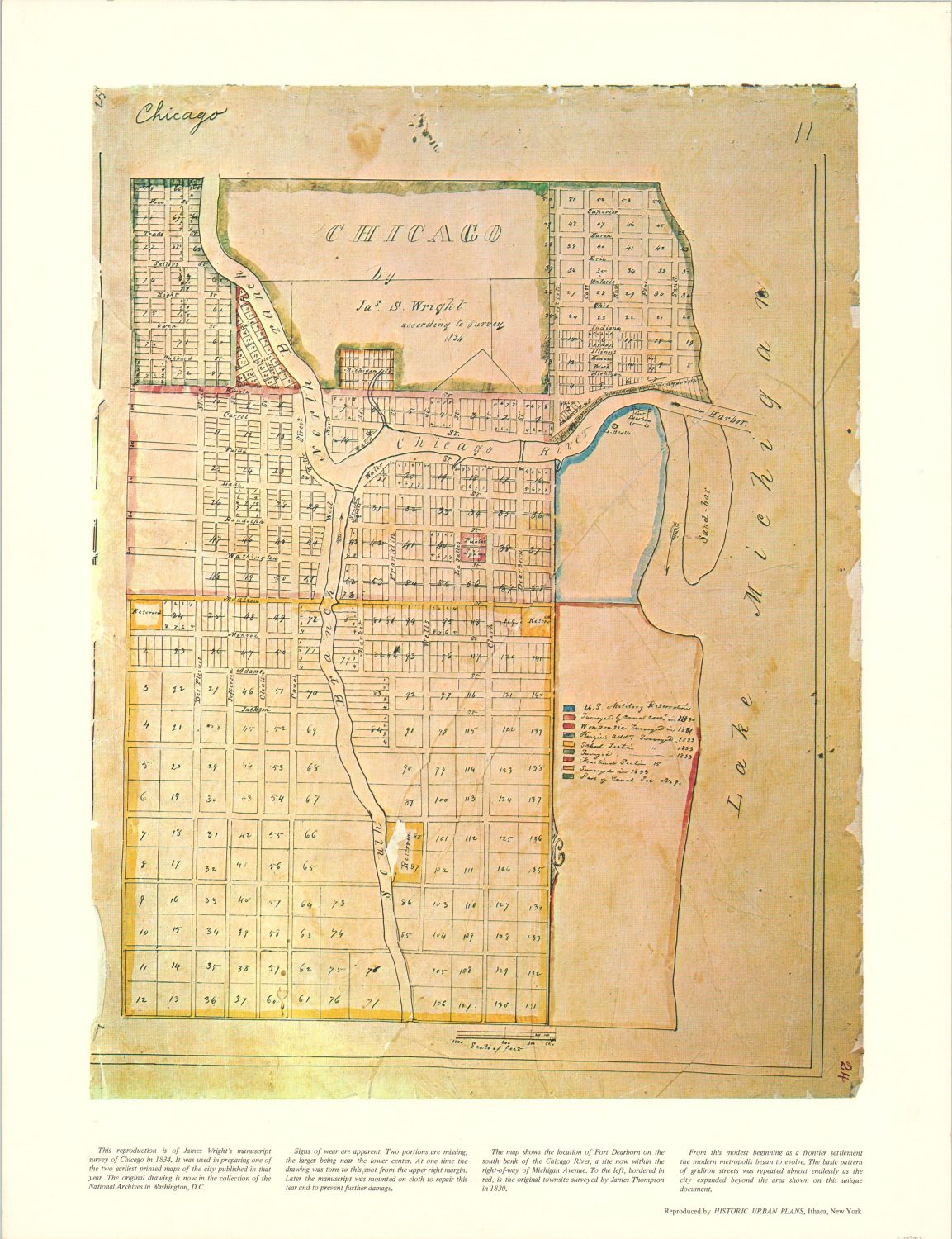

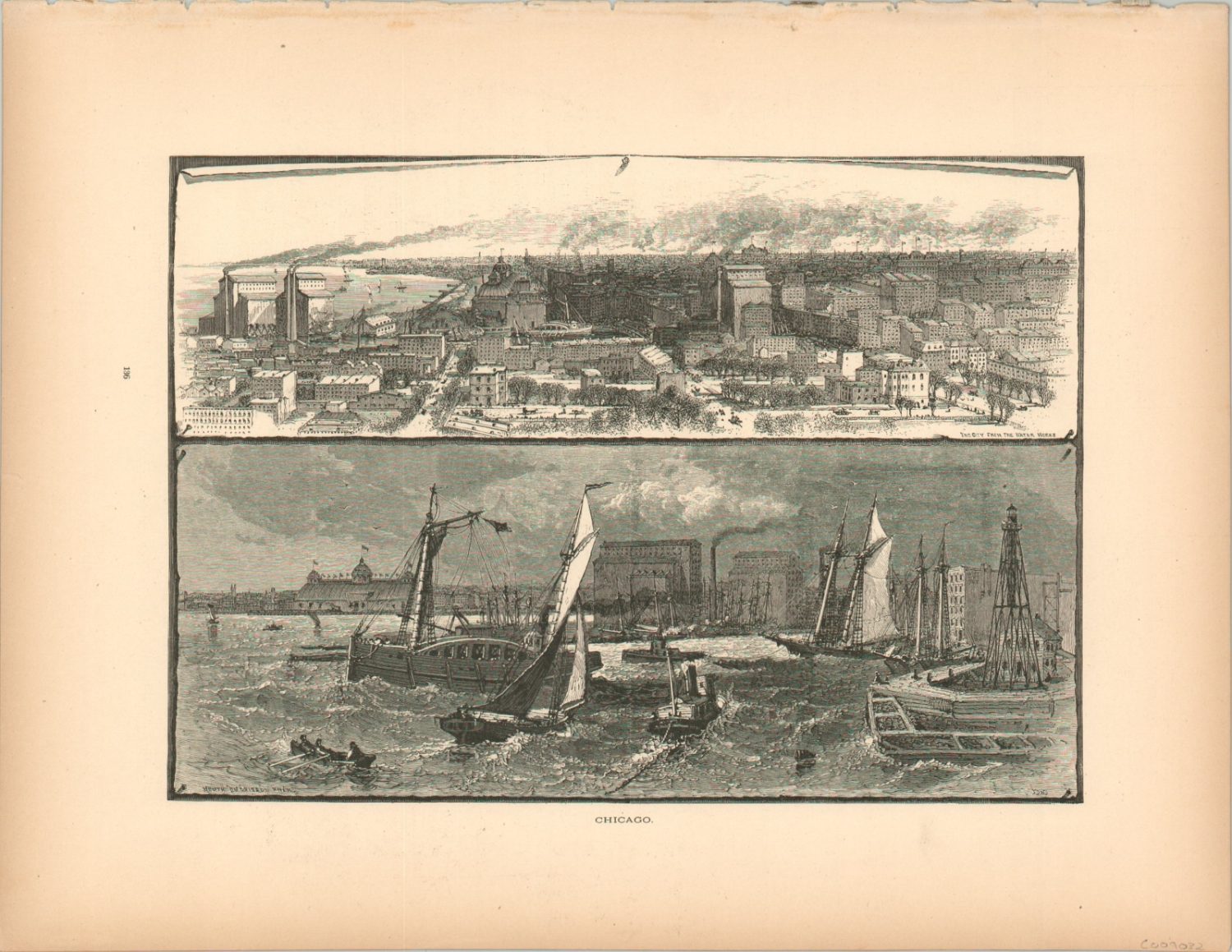

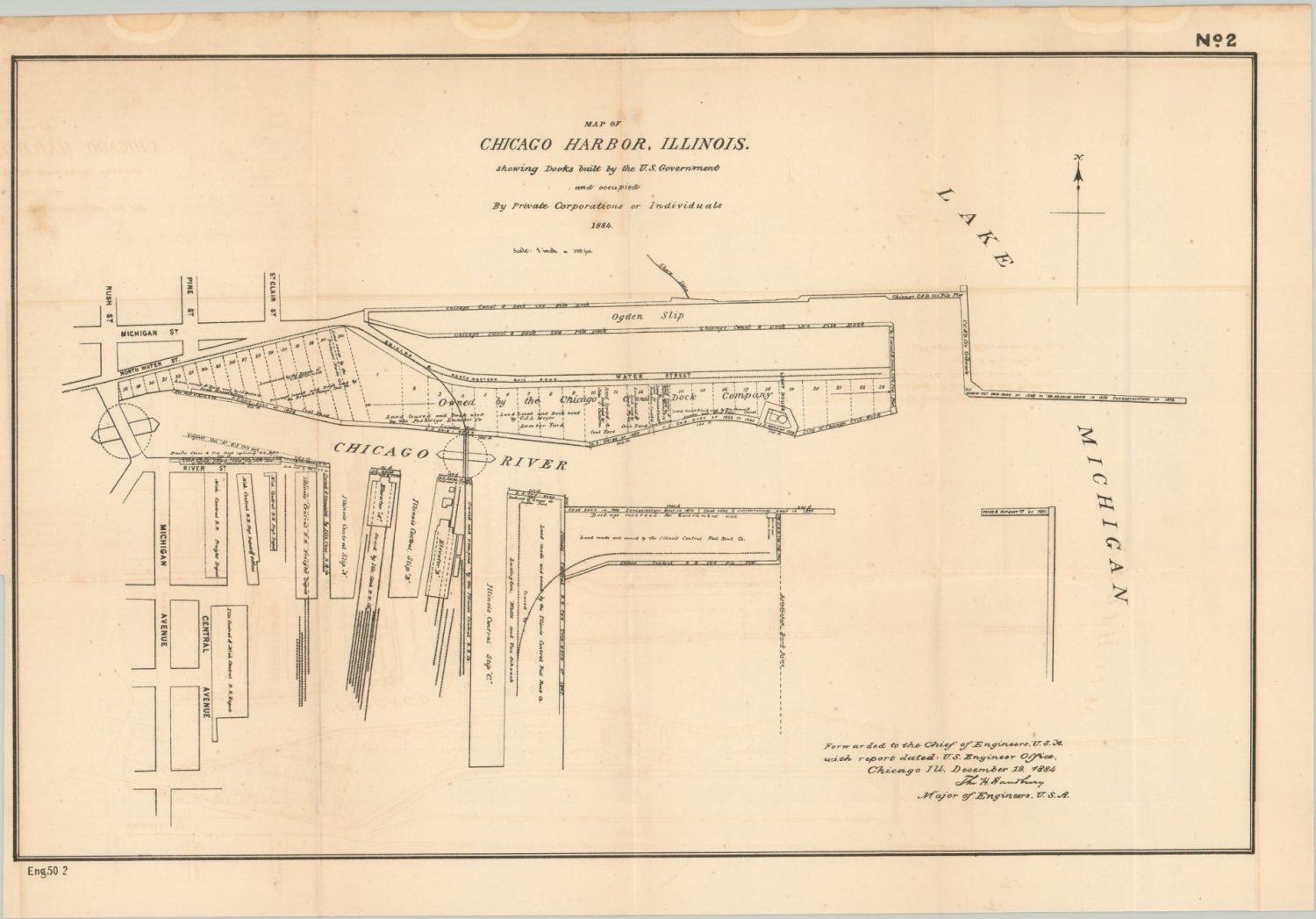

The fledgling community grew quickly, spurred by infrastructure projects like both Fort Dearborns (1803, rebuilt in 1816), the Erie Canal (1825), and the Illinois & Michigan Canal (1848). The first permanent trading post was established in 1779 by Jean Baptiste Point du Sable and commercial activity, focused primarily along the river, would continue to expand in subsequent decades despite setbacks like financial panics, disease, and war. A culture of economic opportunity, established in the real estate and commodities markets, combined with expanding technologies in transportation and construction cemented Chicago’s status as the premier destination in the West.

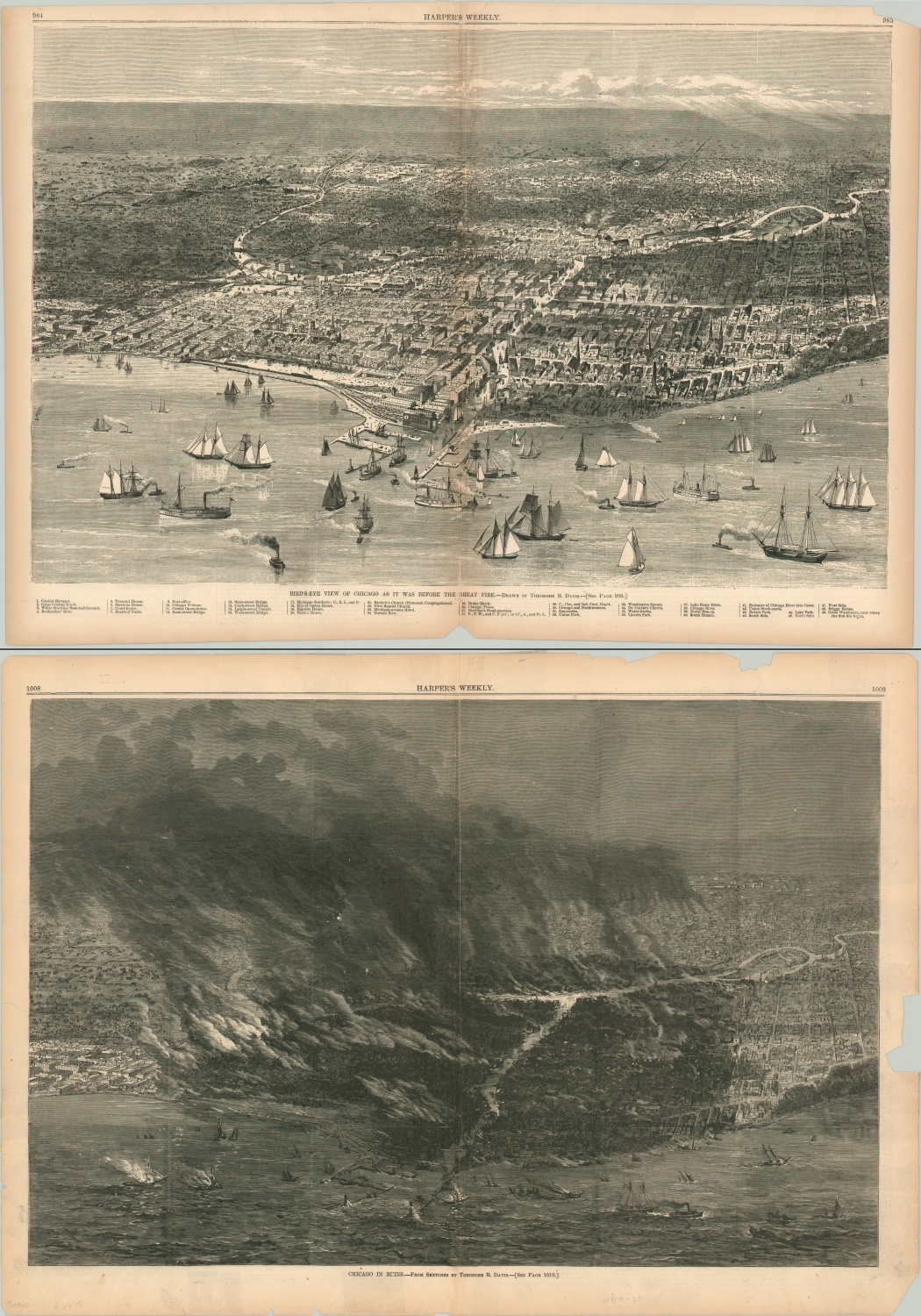

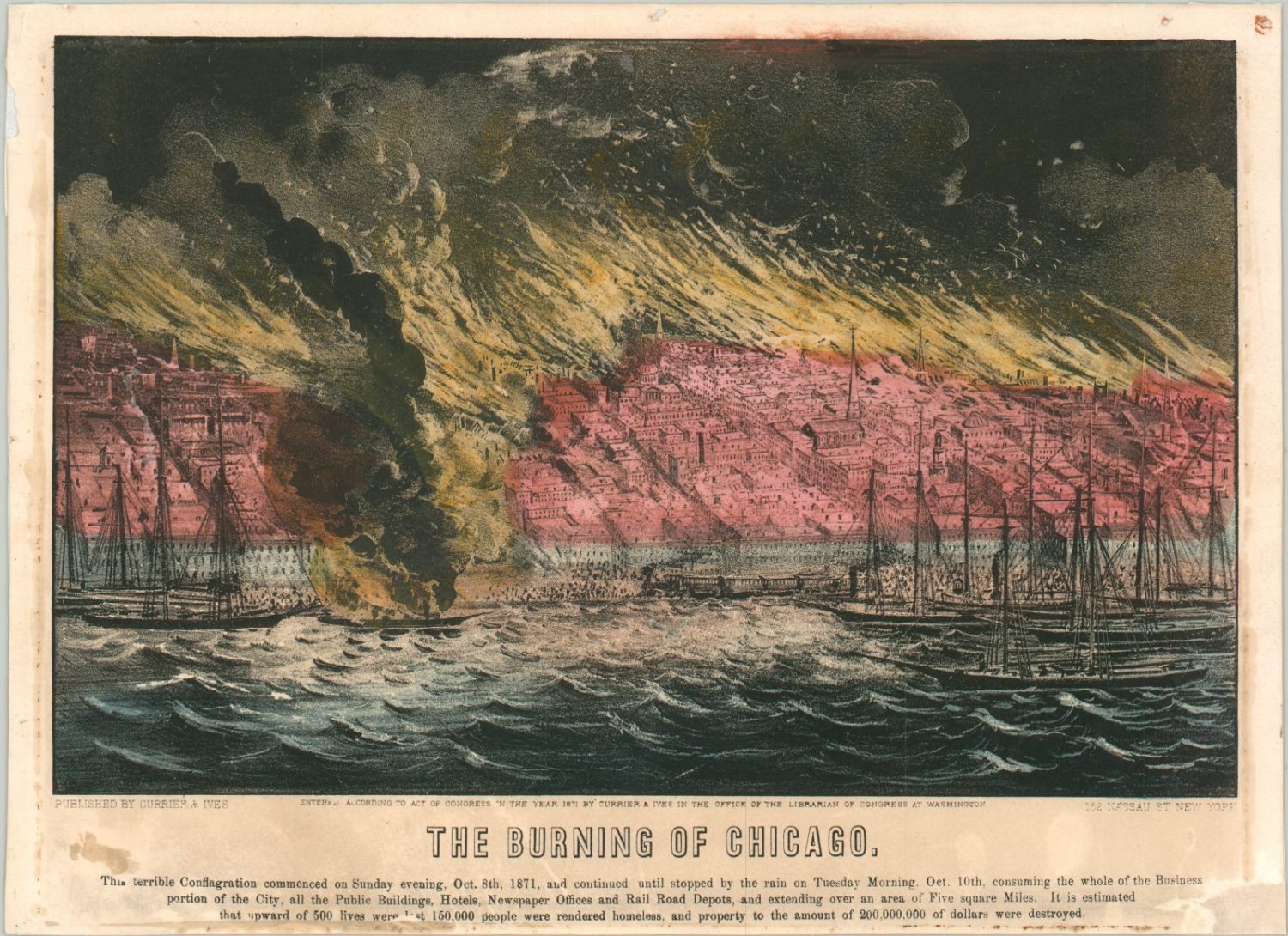

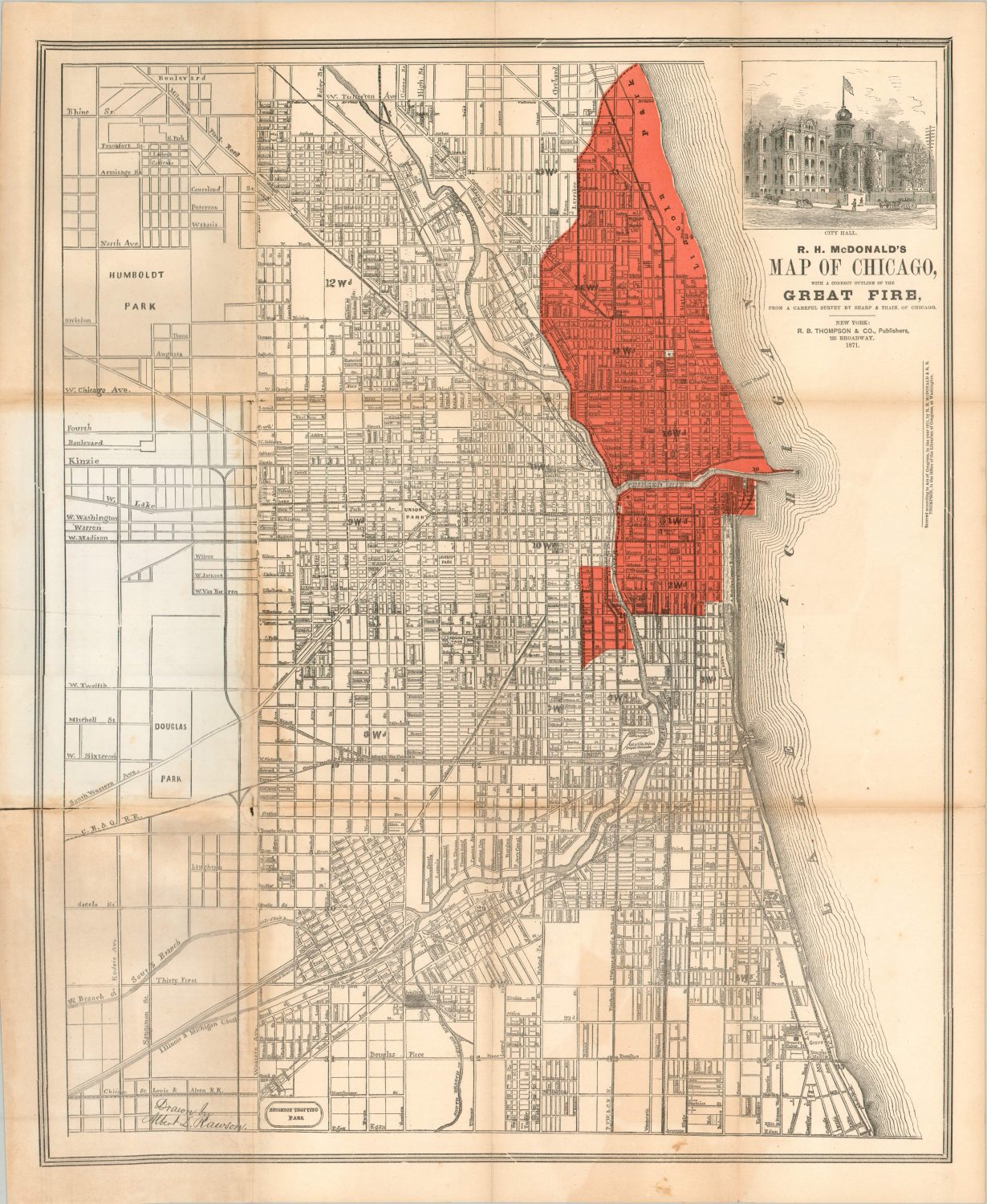

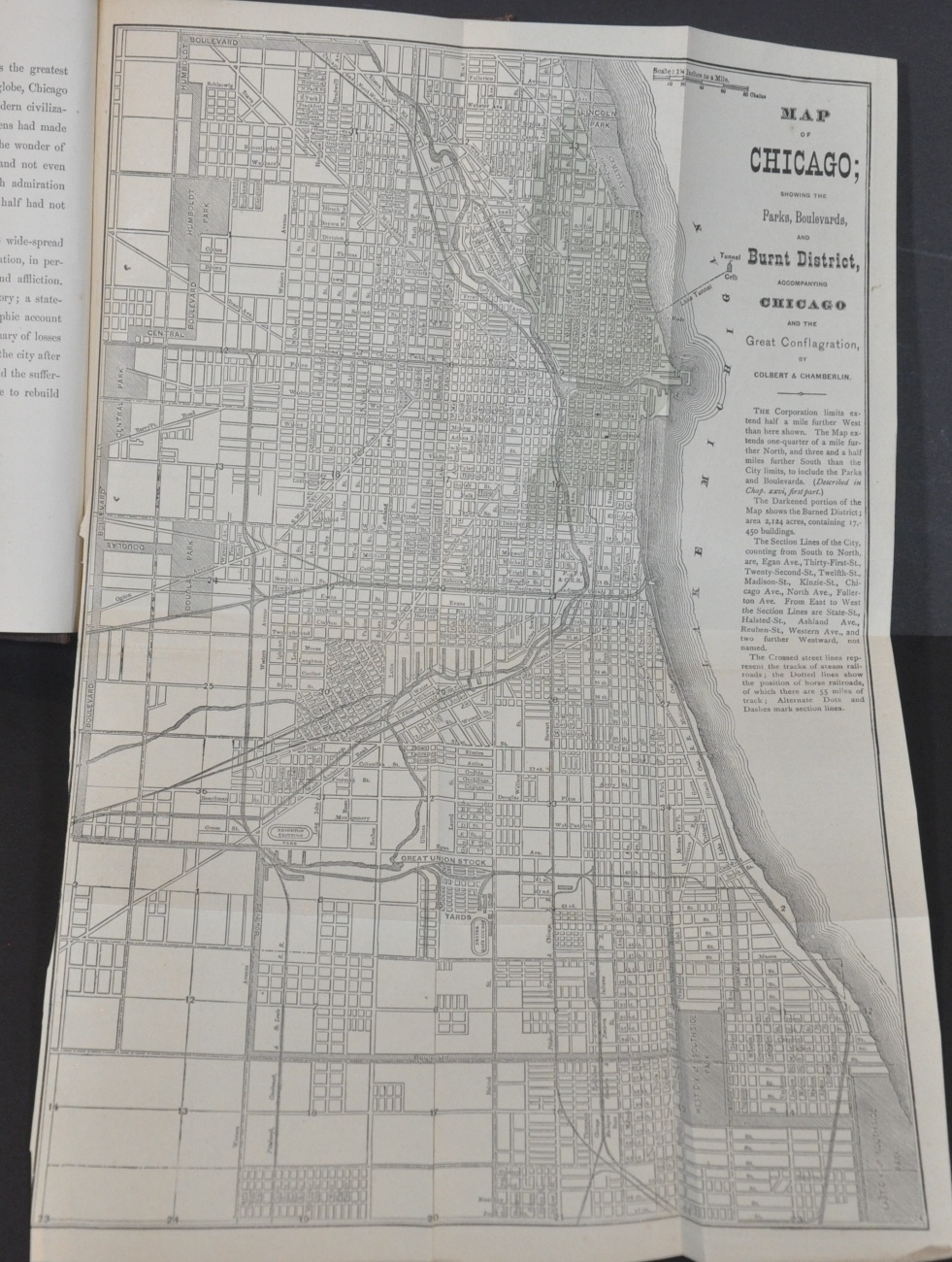

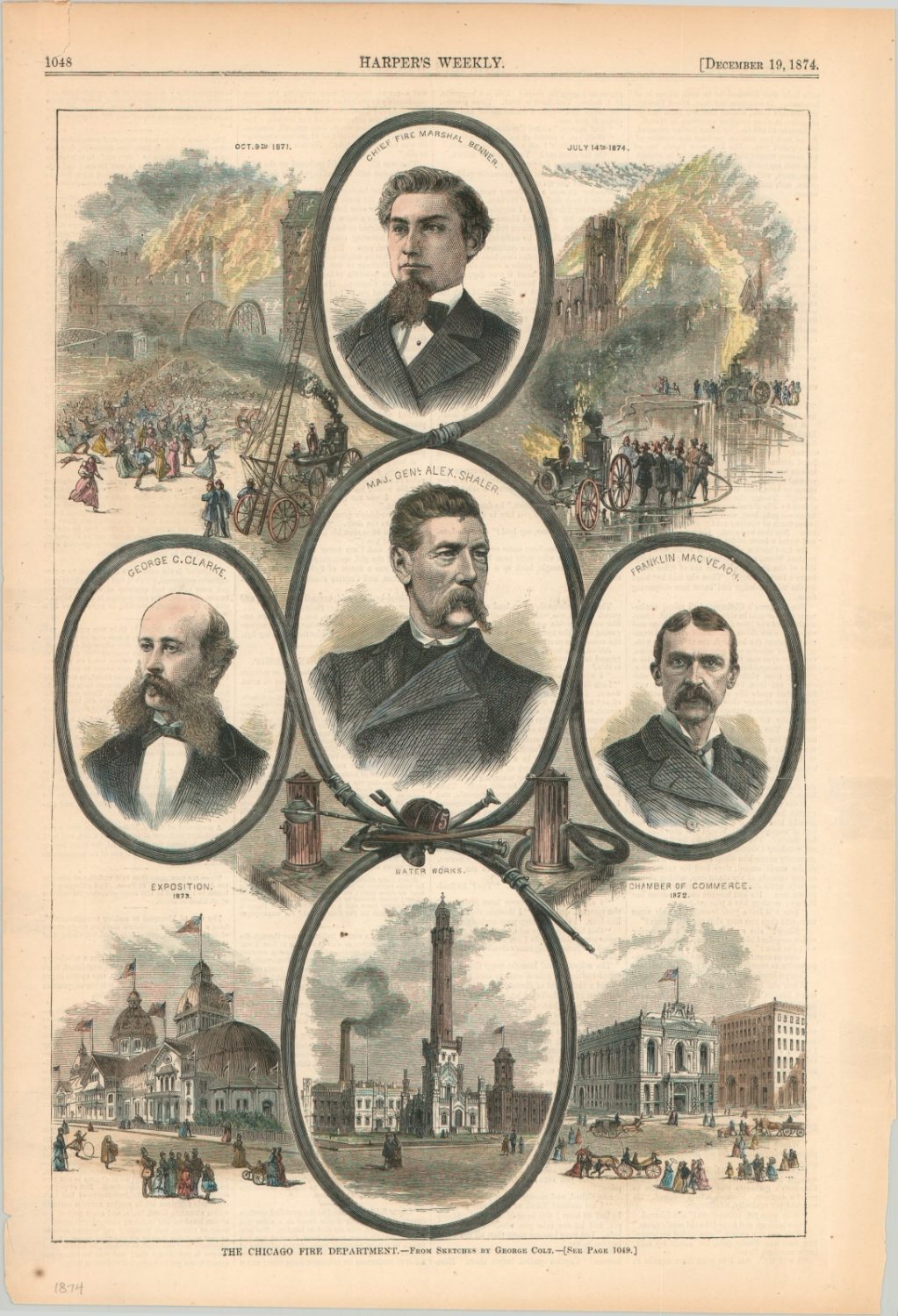

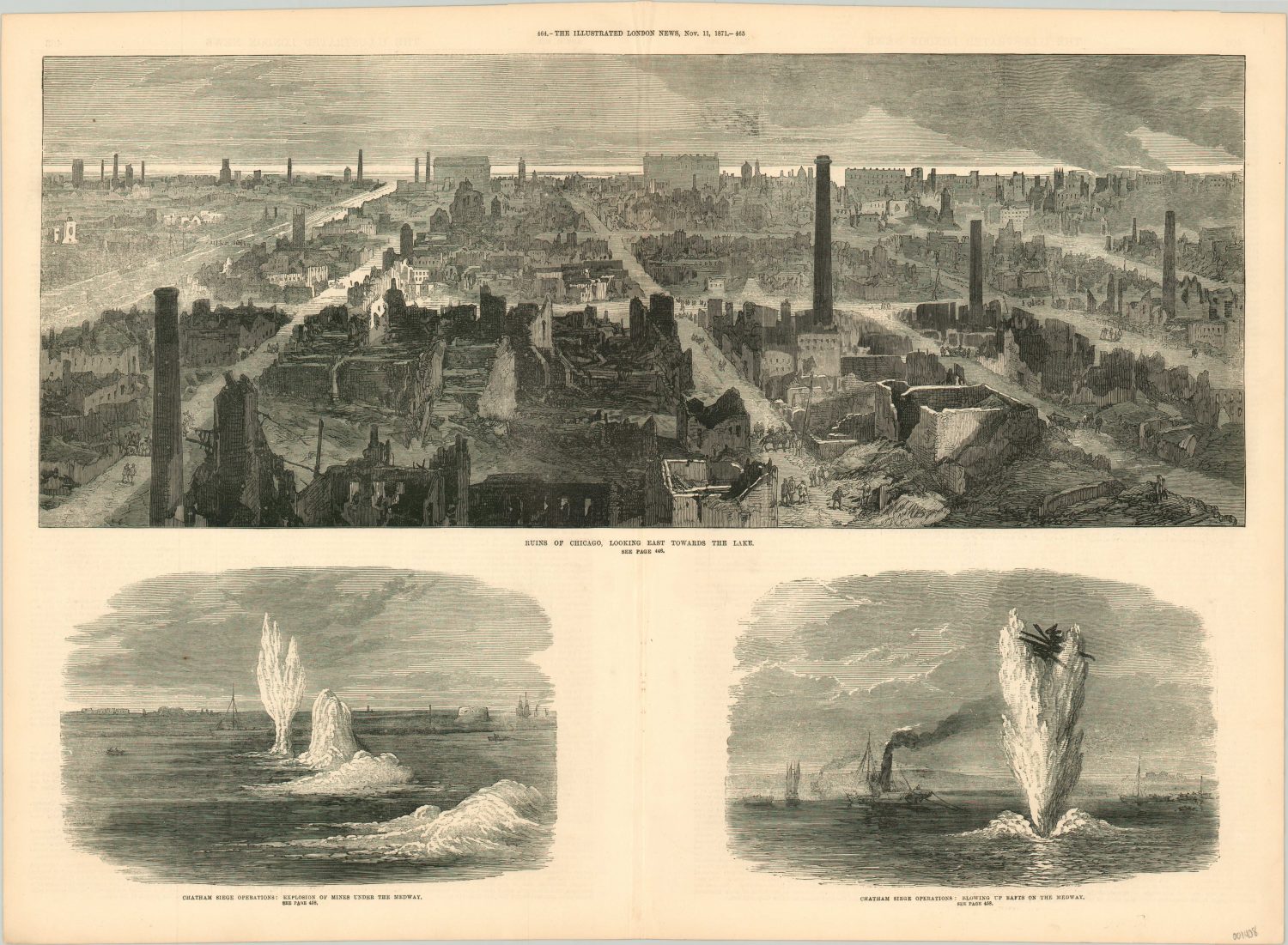

The Great Chicago Fire

It is only with a historical perspective that a city could commemorate one of its worst disasters with a star on the official flag. But it is clear to anyone with a passing knowledge of Chicago’s history that the tale is told along pre and post-Fire lines – like a localized version of B.C. and A.D. The destruction of much of the city’s commercial district was a catalyst for further growth; bigger and better than ever before. But the human suffering was real (200+ dead, 90,000+ homeless) and disproportionately affected the poorer classes.

On the evening of October 8, 1871, a fire started on DeKoven Street, near 12th and Halsted on Chicago’s Near South Side. Though the culprit is often claimed to be a cow owned by Catherine O’Leary, who lived nearby, the true cause of the spark is unknown. But due to a parched summer, windy weather conditions, an abundance of available fuel, and inadequate firefighting capabilities, a number of smaller fires grew into an enormous conflagration over the course of the following day. Refugees fled in droves, looking for safety on the prairies, beaches, and cemeteries with what few belongings they could carry.

By the time the blaze sputtered out in the early morning hours of October 10, over 17,000 buildings in the business section and North Side had been consumed. Nearly 3.5 square miles – approximately 1/3rd of the city – were destroyed. But the legend goes that rebuilding began the next day, with John McKnight’s fruit and cider stand available to refresh those sifting through the rubble. Donations poured in from around the globe, distributed locally by the Chicago Relief & Aid Society. Railroad tracks, lumber yards, and wharves remained largely untouched. Within a few weeks, thousands of temporary structures dotted the formerly burned-out district and tons of debris had been pushed into Lake Michigan. In fact, Chicago’s rapid rise proceeded at such a pace that few lessons were learned, and another large fire erupted in 1874!

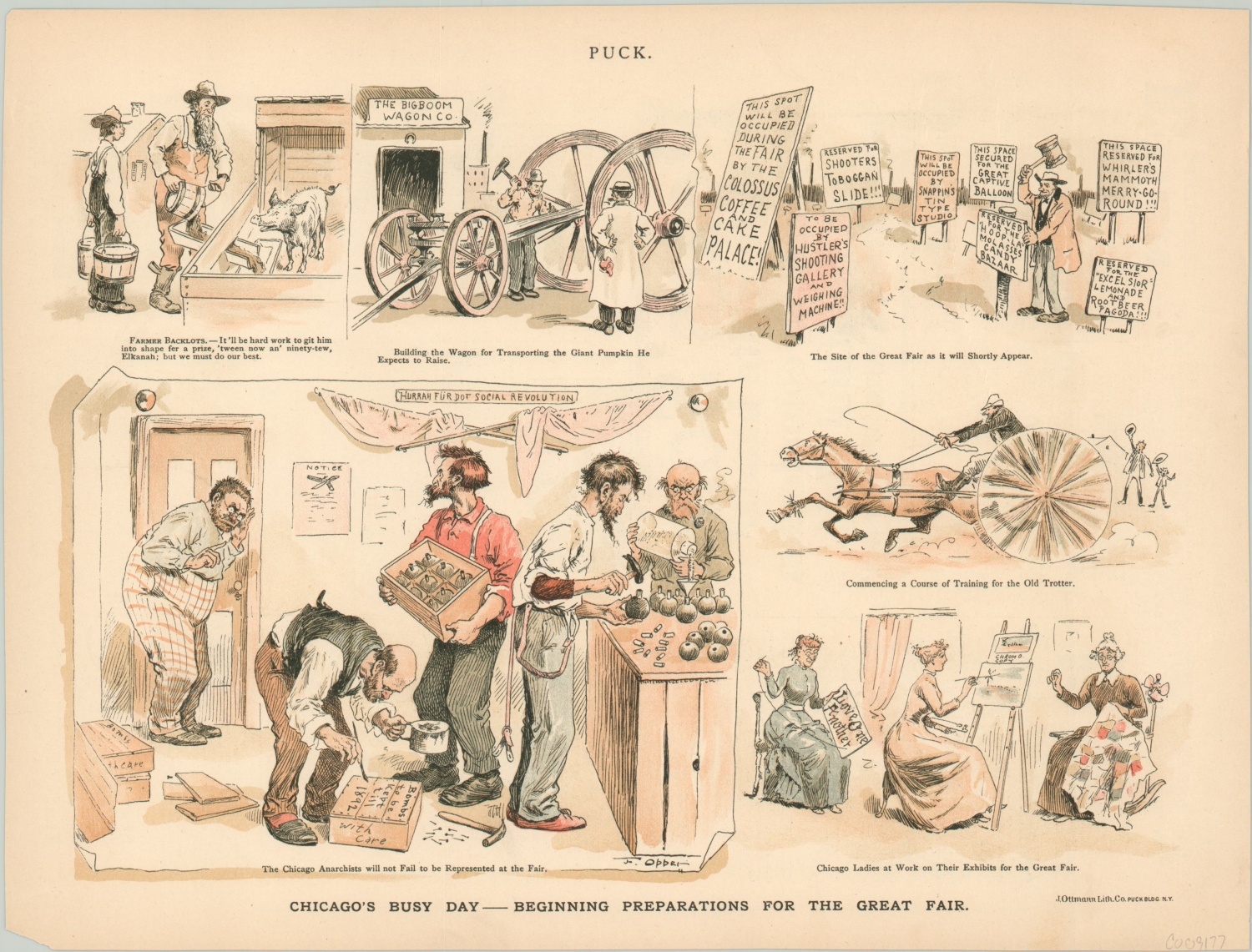

The Columbian Exposition

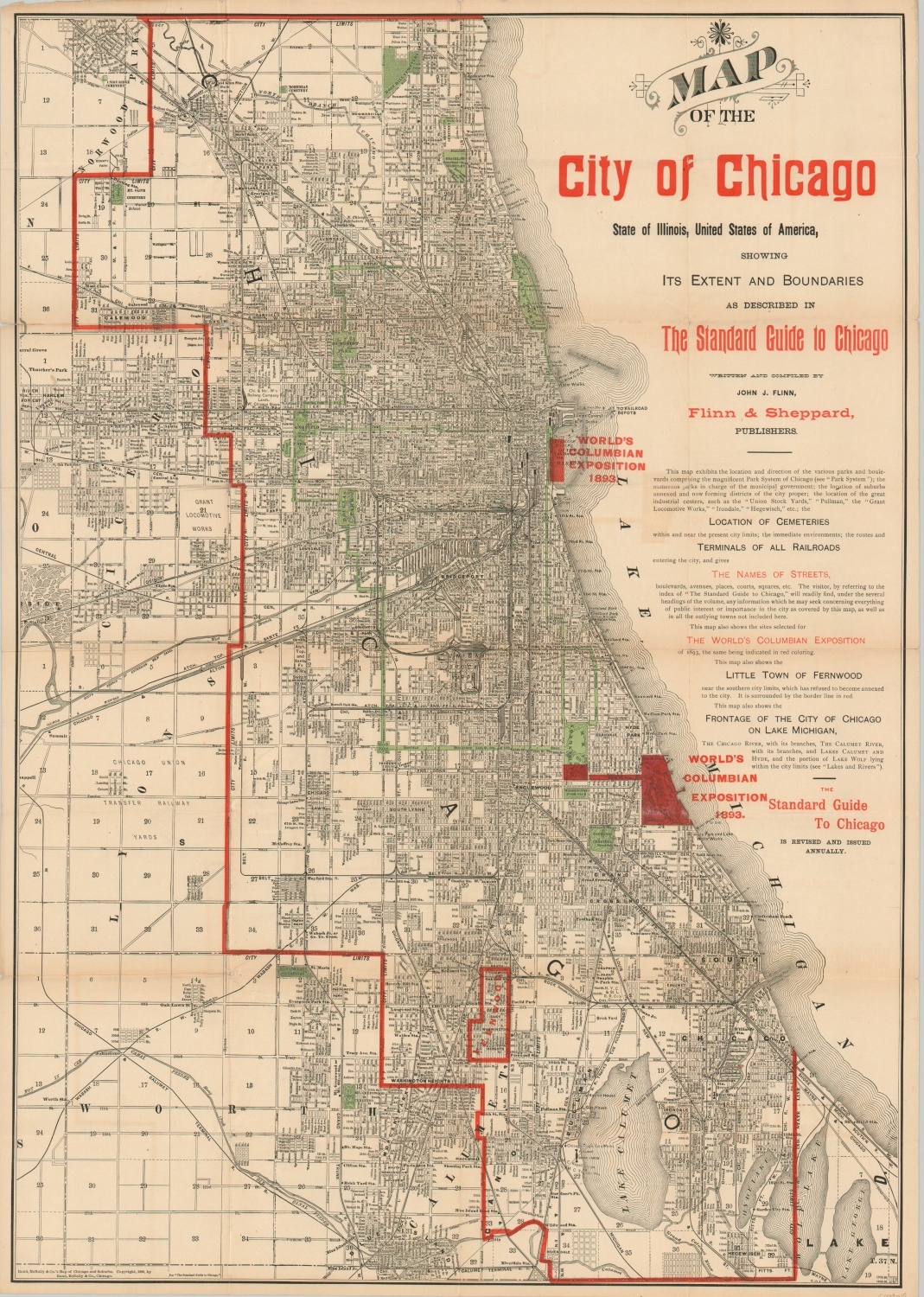

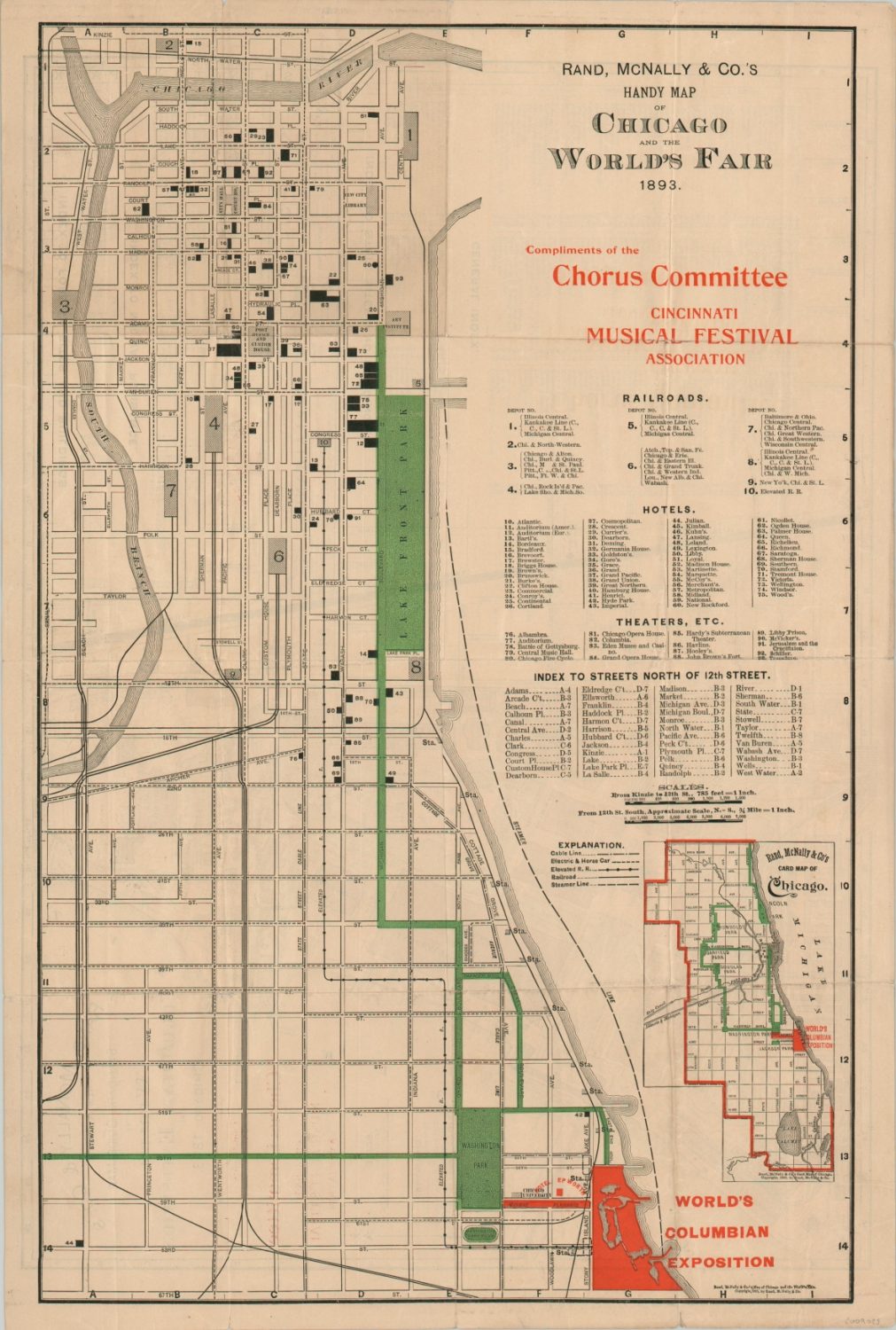

Civic leaders in several prominent cities across the globe considered holding a World’s Fair to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the New World. Chicago’s financiers, led by iconic names like Charles Yerkes, Marshall Field, and Cyrus McCormick, pledged more money than their competitors (the closest was New York), and Congress assigned the honor of official host in 1890 – less than 20 years after the fire.

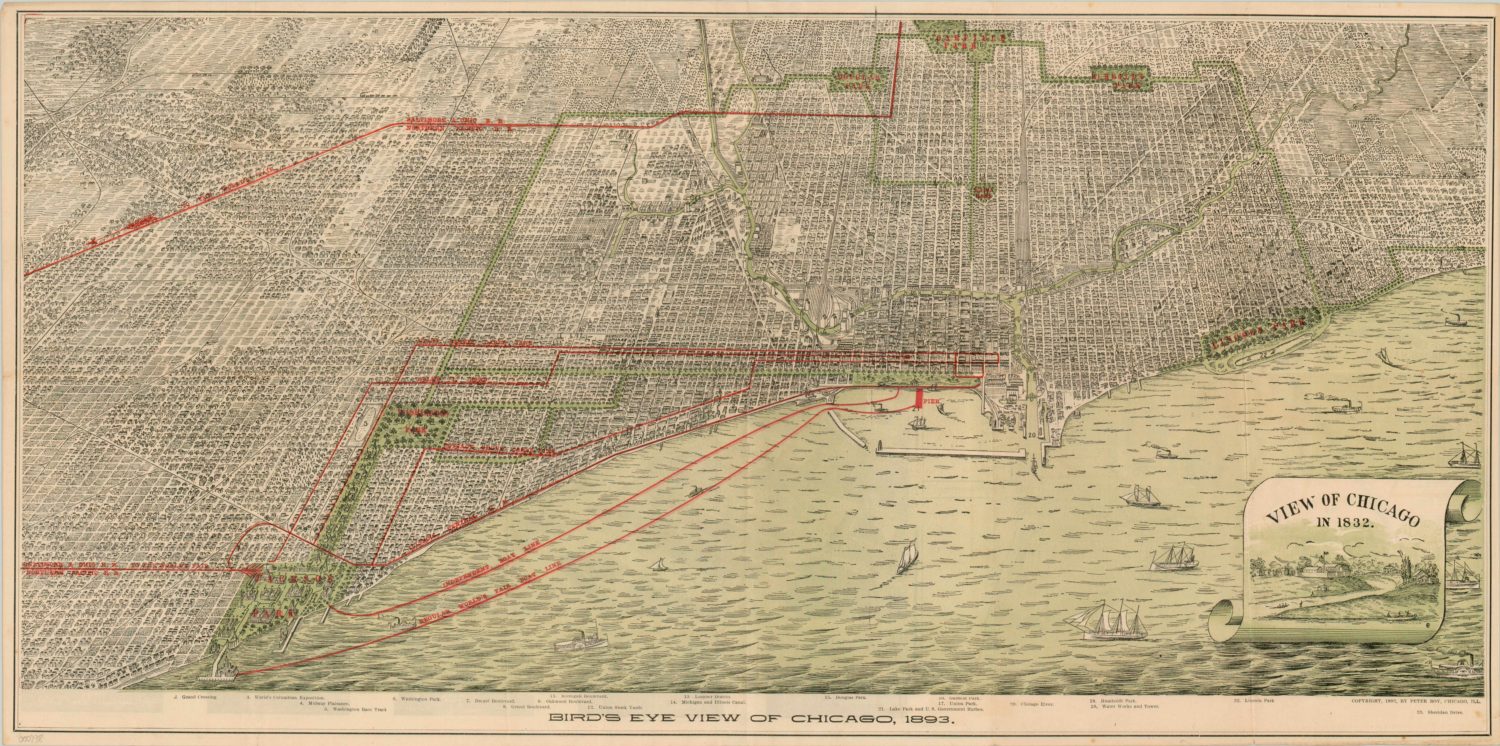

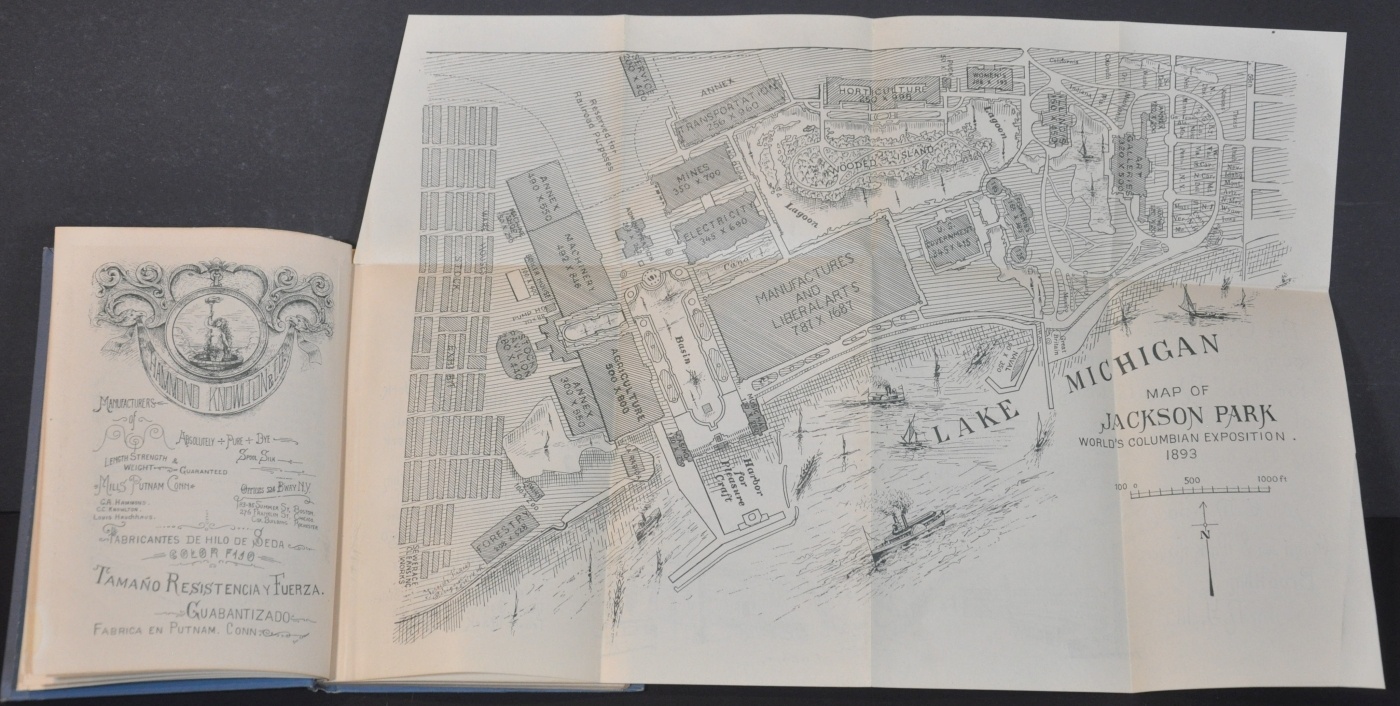

The Columbian Exposition was held at Jackson Park between May 1 and October 30, 1893. During that period, the fair averaged over 150,00 visitors per day from all over the world. Daniel Burham, the chief planner, oversaw the construction of a fantastic ‘White City’ with buildings modeled after classical architecture displaying a glittering plaster facade. Elaborate fountains and statues were interspersed between the main structures, casino, industrial exhibits, state buildings, and wooded lagoon. Electric lighting provided dazzling illumination at night.

The adjacent Midway Plaisance also had its share of wonders, though they contrasted sharply with the Neo-Classical design of Burham’s White City. Here one could see circus performers and belly dancers, ride the gigantic Ferris Wheel, and walk through a display of global architecture populated with native people- crudely approximating a trip through ‘civilization.’ Shopping, entertainment, and exotic concessions lasted well into early morning hours and did not require a ticket to the main gates.

Though few of the original structures from the Midway Plaisance and the White City survived, the legacy of the Columbian Exposition is tangible. The momentous event solidified Chicago as America’s ‘Second City’. Worldwide exposure to commercial opportunities helped expand a favorable business environment. It encouraged the development and ridership of the ‘L’ with a new line to Jackson Park. Much of the street grid and park system, including the wooded lagoon, can still be visited today. The Fine Arts Palace was rebuilt permanently in limestone and became the Museum of Science and Industry. Even the term ‘Midway’ became a common name for a place of amusement. Perhaps more ominously, the fair provided an early look at the consumerism of the 20th century, with hordes of inexpensive goods and souvenirs produced for sale.

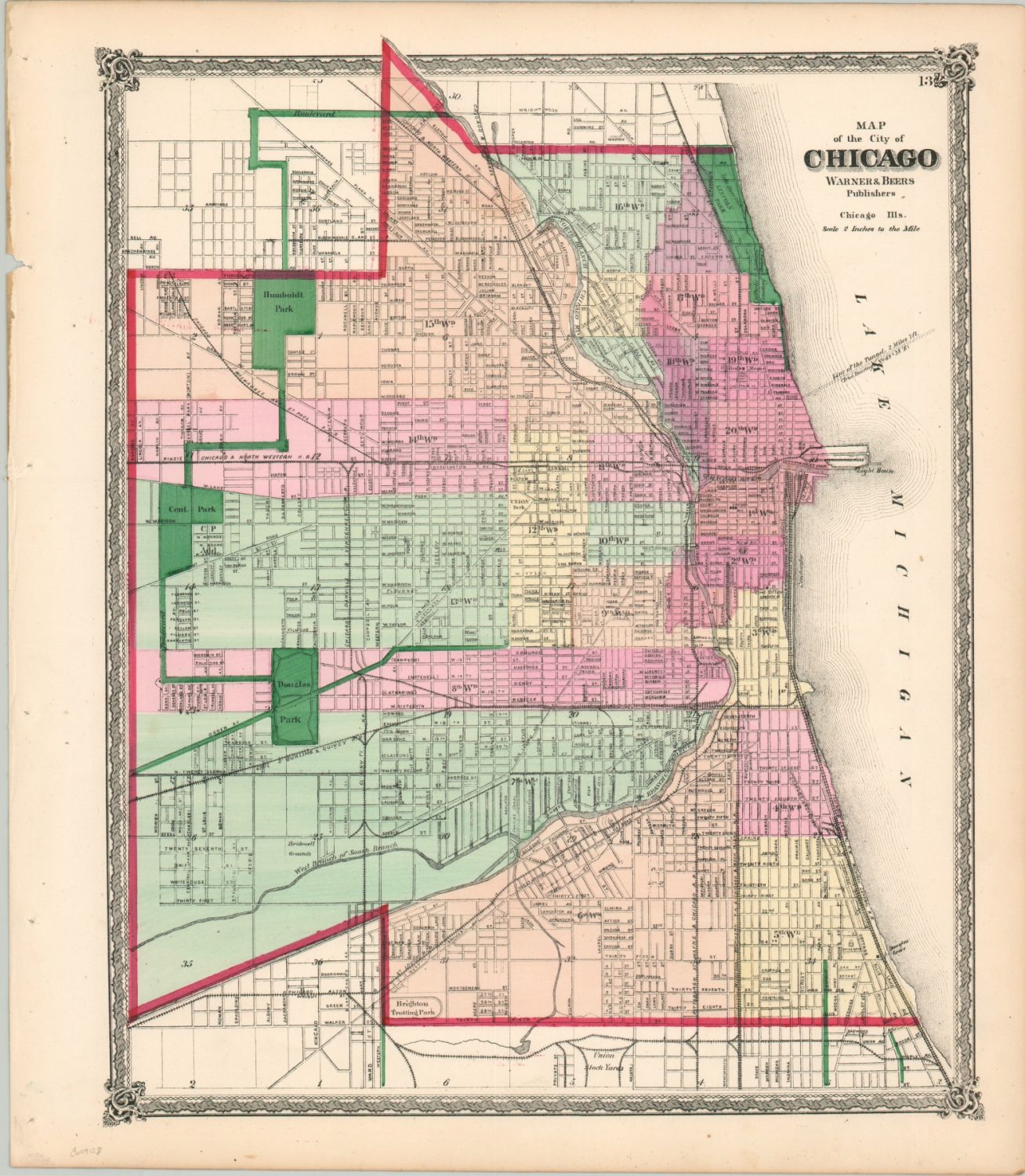

Growth of the ‘Second City’

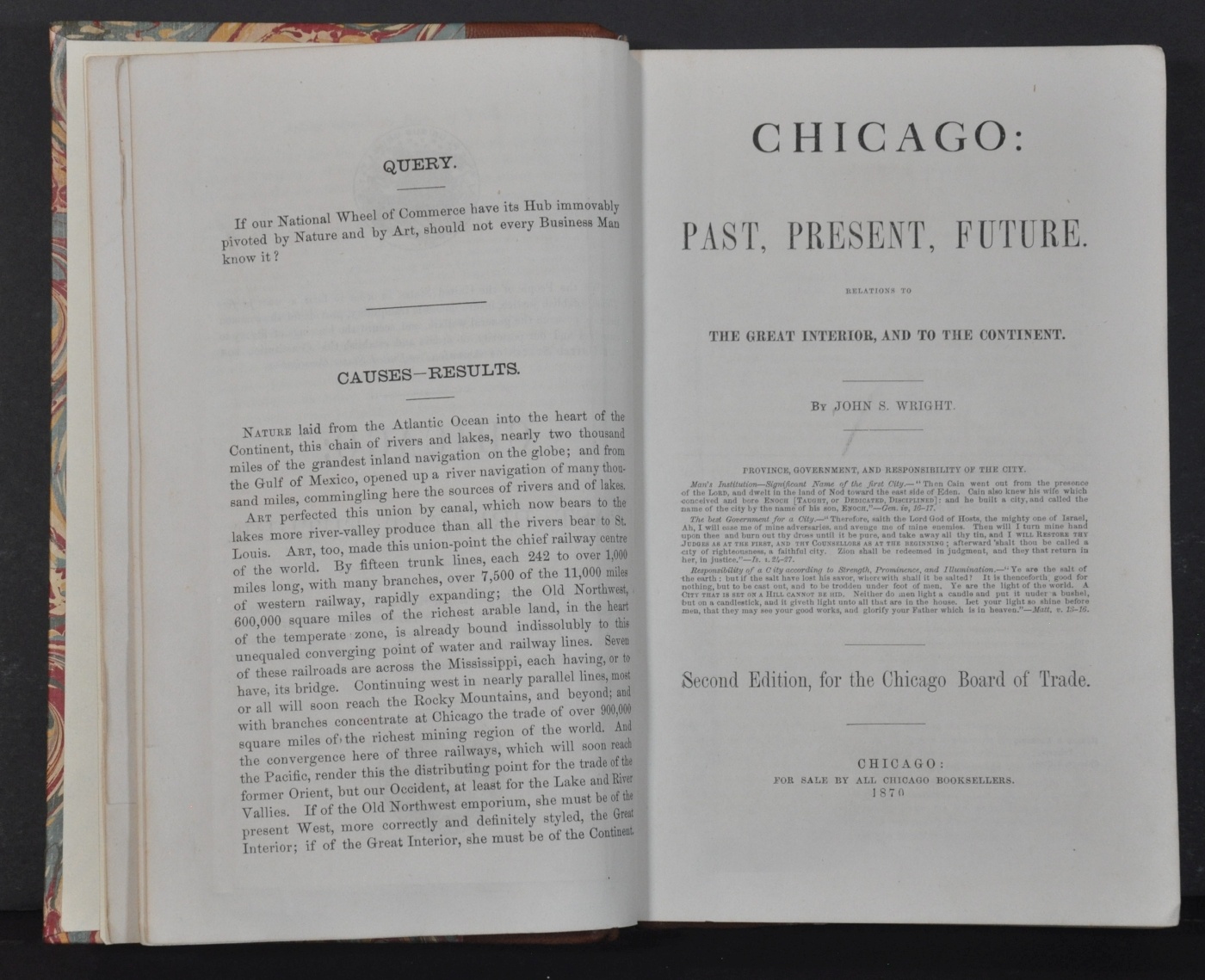

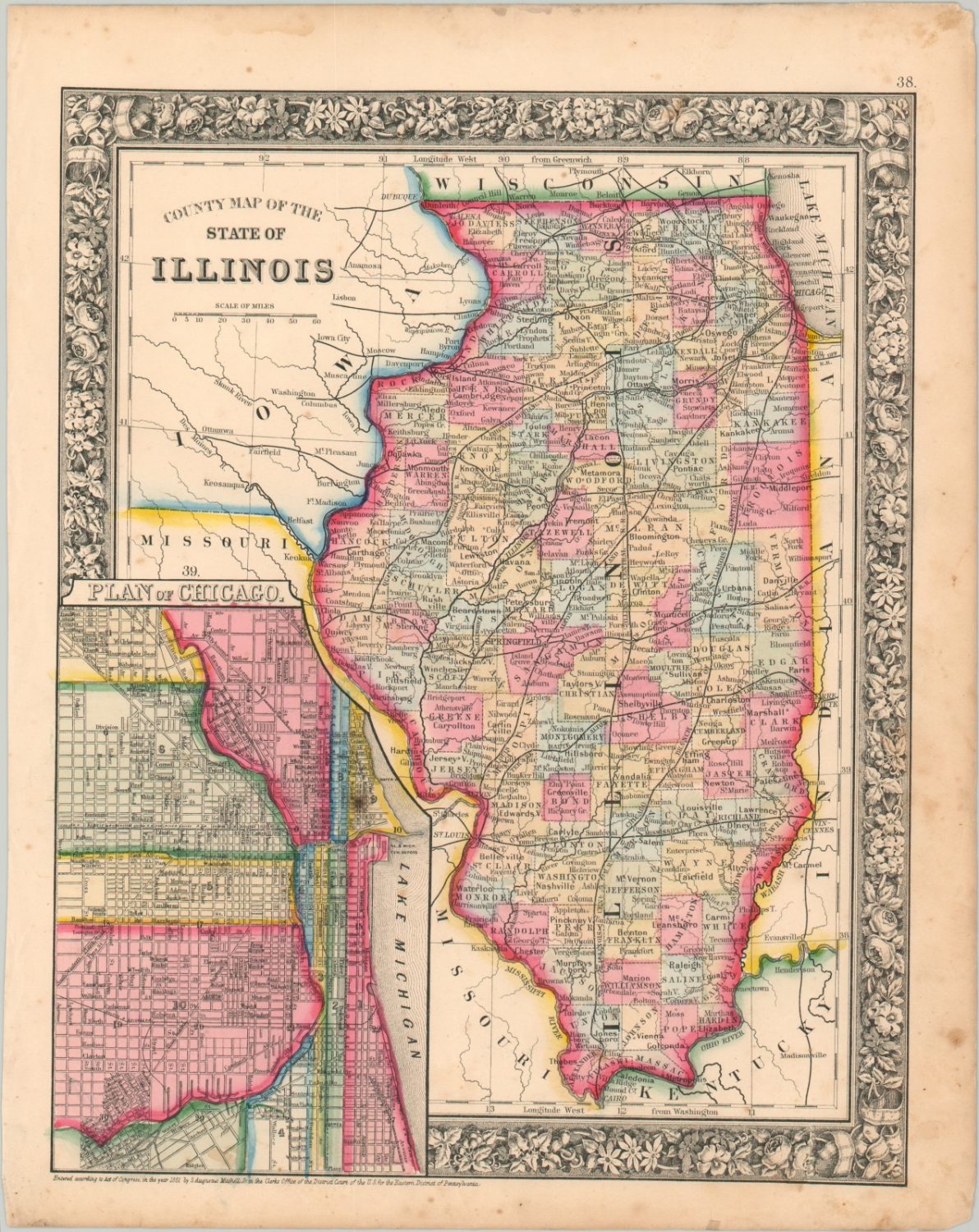

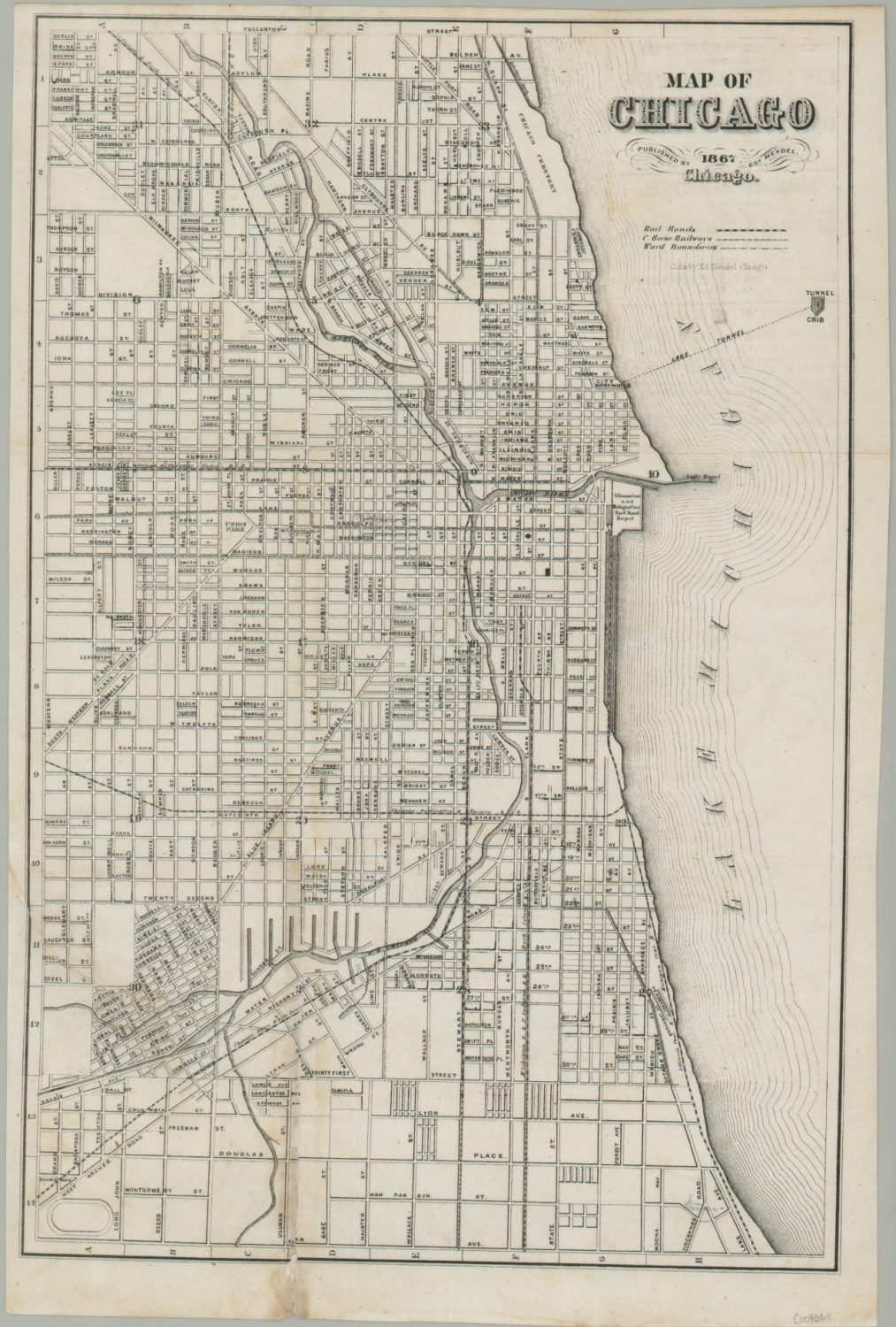

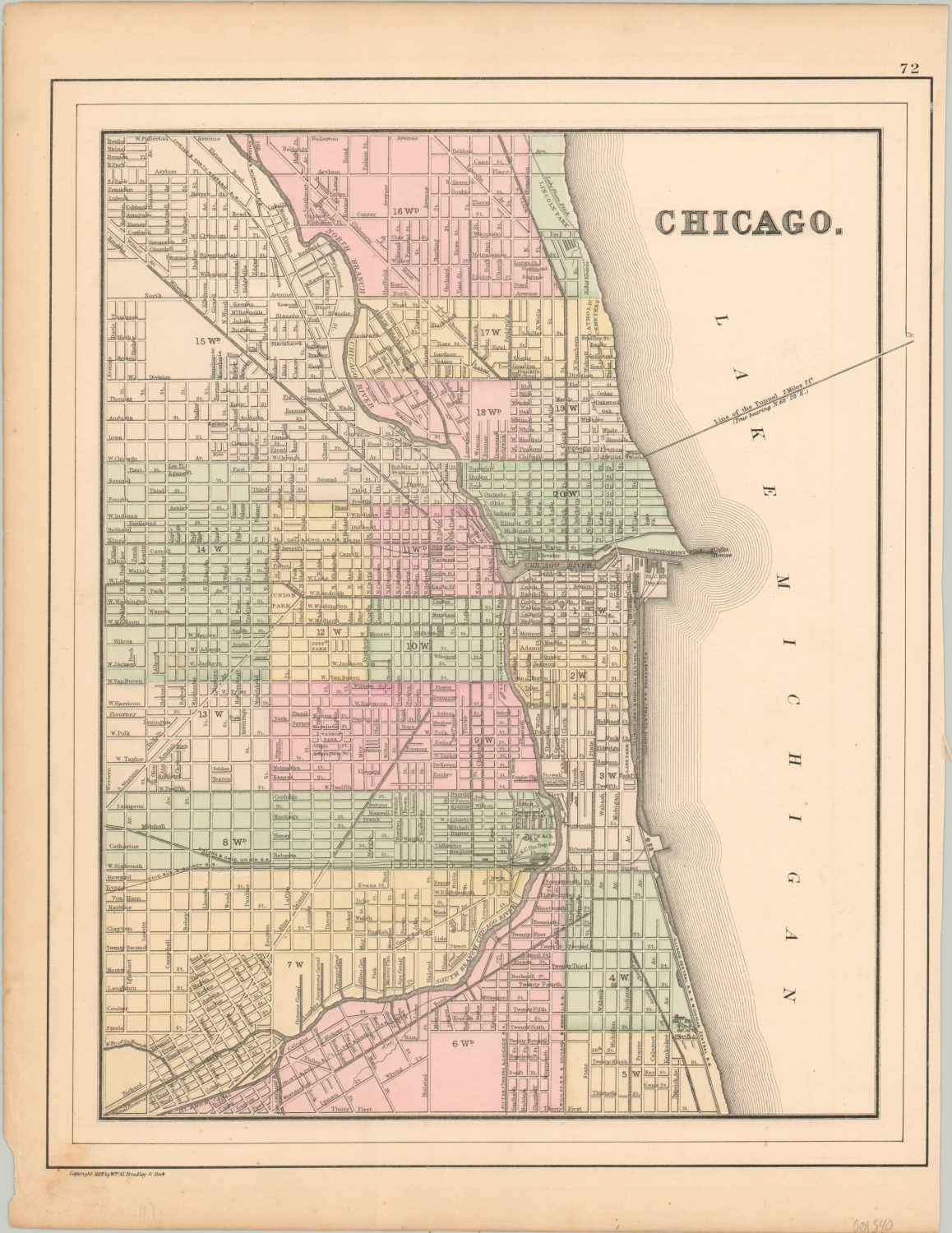

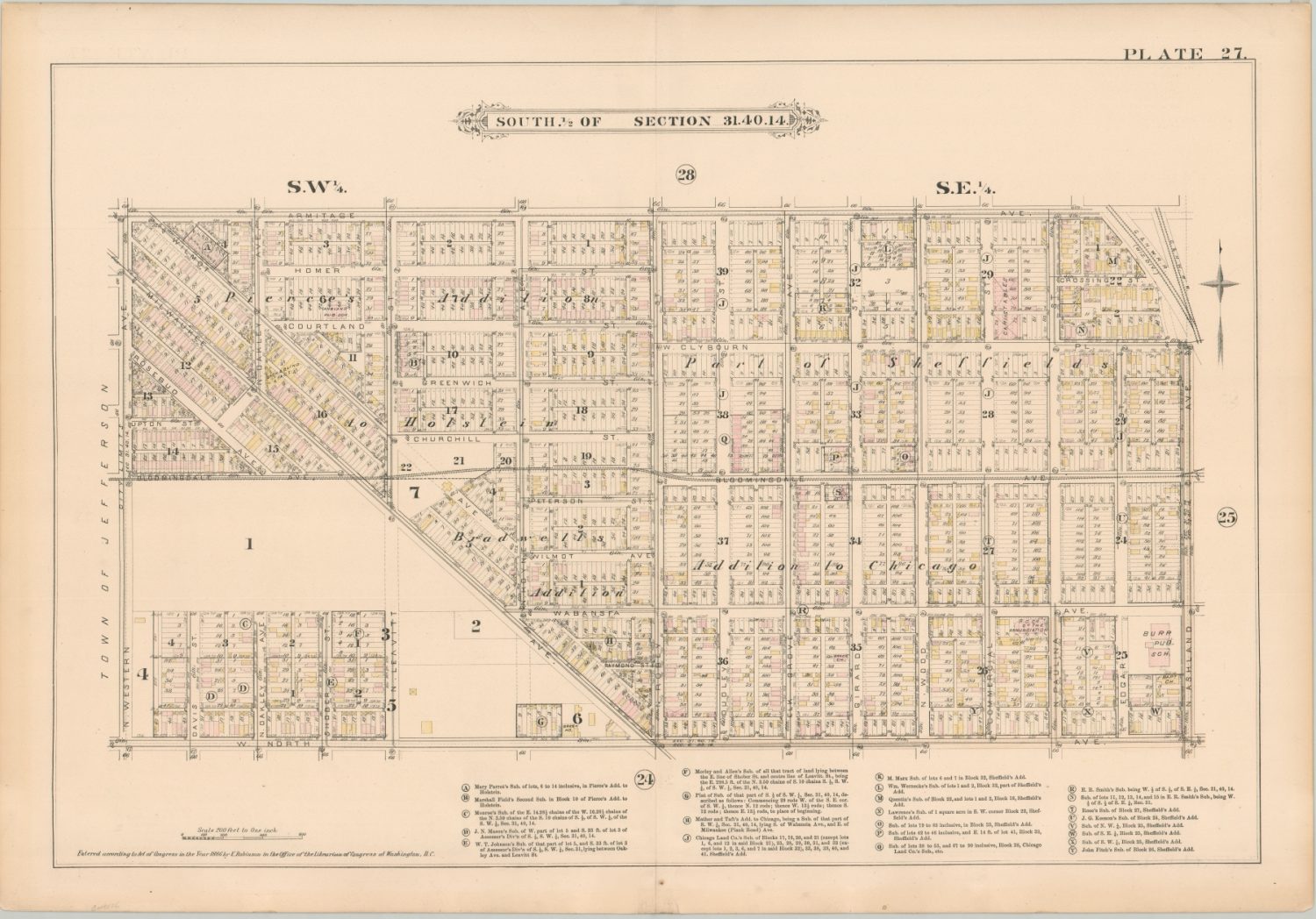

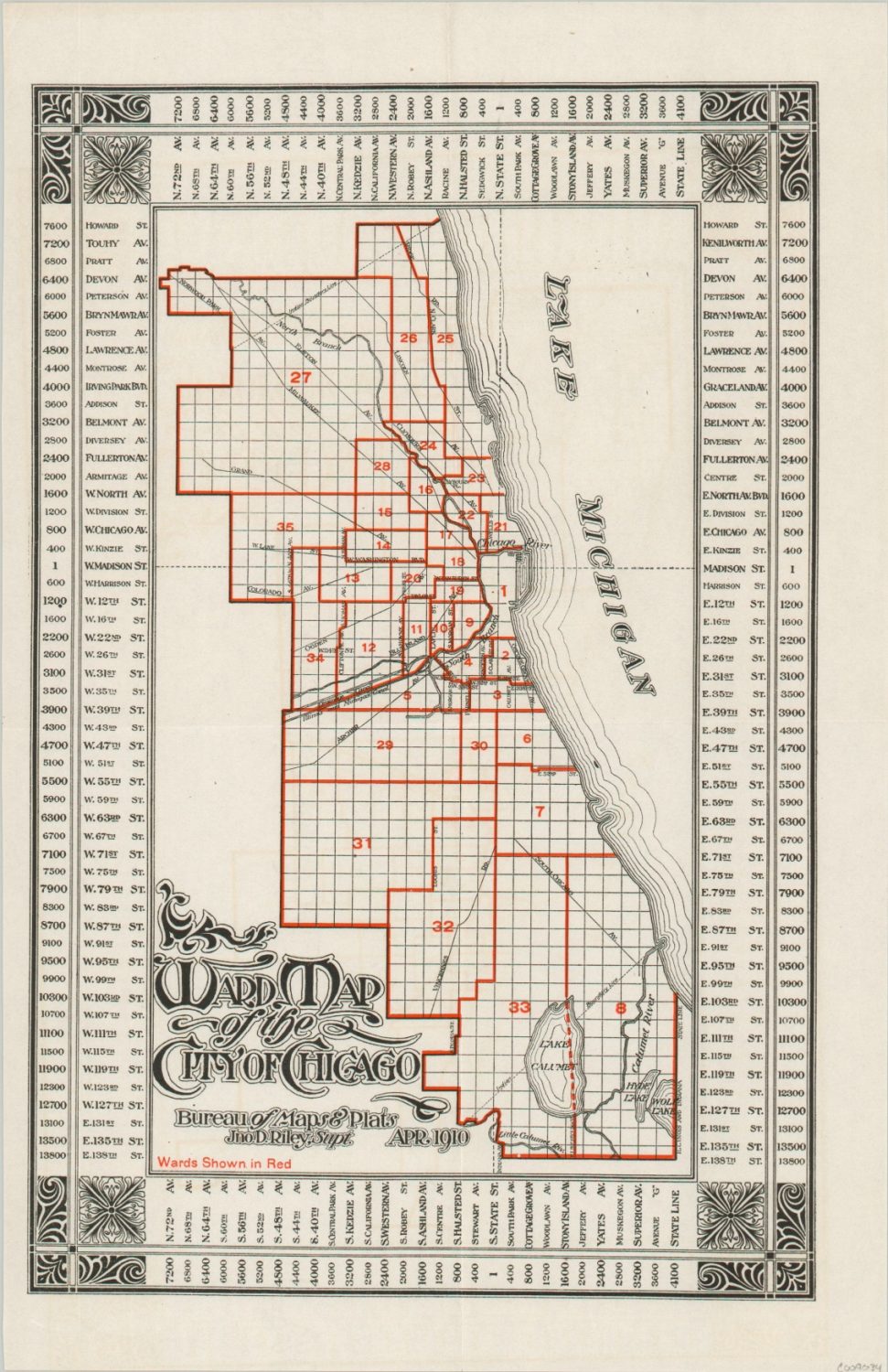

It took only 57 years for Chicago to become the second-largest city in America, after incorporation as a town in 1833. The population had grown from less than 3,000 to over 1 million in the intervening period. There is a myriad of reasons for the city’s tremendous growth in the second half of the 19th century. New construction techniques like balloon frame housing, plentiful nearby commodities, easy transportation access via water, plank road, and eventually rail, are among them. Abundant economic opportunities in a new land where cash is king attracted people of all kinds from across America, and eventually, the world.

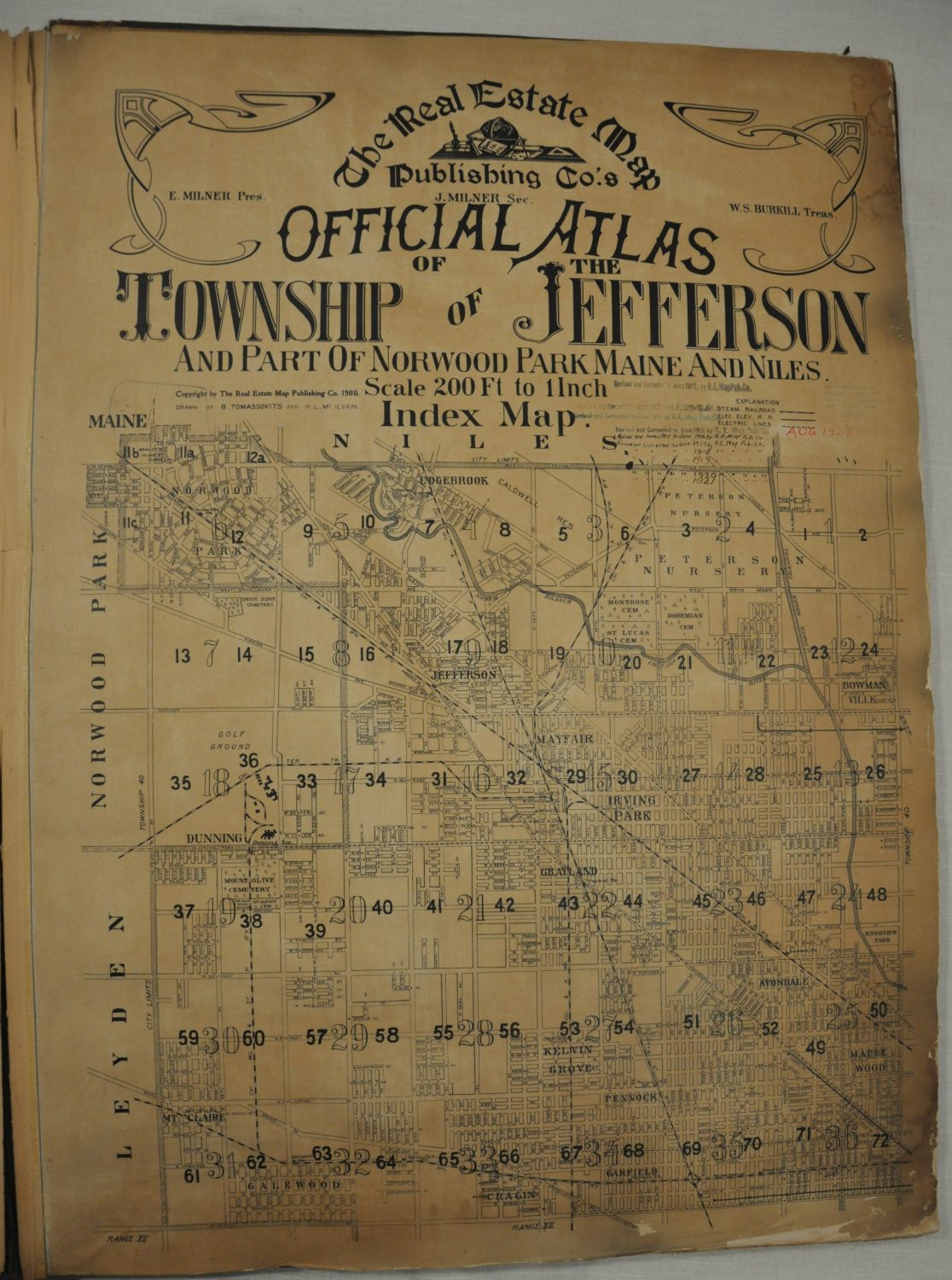

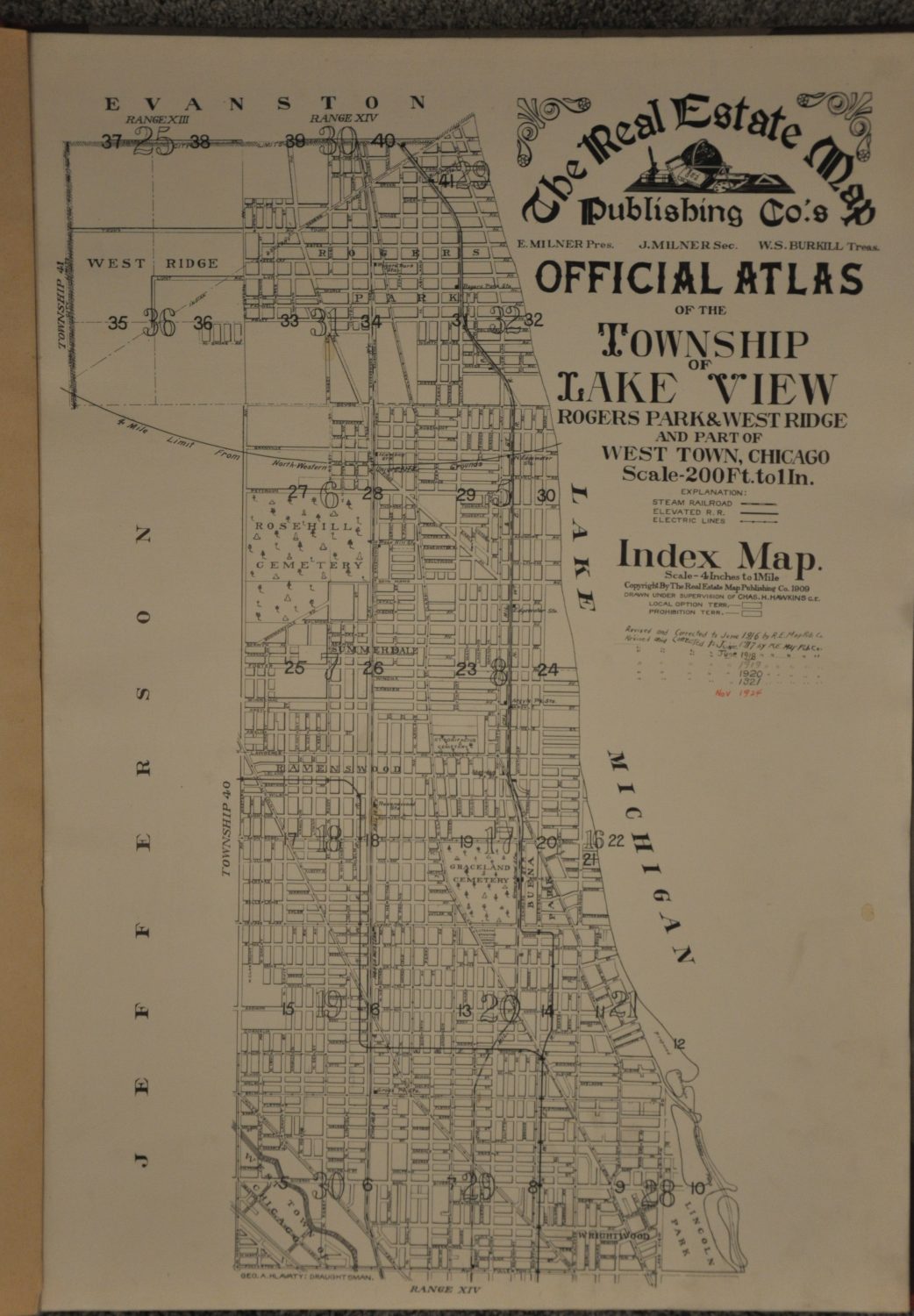

The footprint of the city grew accordingly, from a little under 10 square miles in 1837 to nearly 185 square miles by the end of the century. Legislative acts, referendums, and elections annexed adjacent suburbs numerous times, with the largest occurring in 1889 (these also helped contribute significantly to Chicago’s population growth). Promises of better city services and infrastructure were often enough to encourage local communities to vote in the right direction, but political coercion was not unheard of. A wall of resistance was met in the suburbs, and the last major residential annexation was Mount Greenwood in 1927.

Chicago grew not only outwards, but upwards (quite literally). In the late 1850’s many of the city’s buildings and sidewalks were raised several feet to accommodate new gravity-fed sewer lines. The Home Insurance Building, constructed in 1885, is considered to be the first true skyscraper. A steel skeleton allowed the edifice to reach a towering ten stories, but it was destroyed in 1931. The architectural design and technology, pioneered by William LeBaron Jenney and his assistant Louis Sullivan, was far more permanent as the foundation of the ‘Chicago School.’

A Century of progress

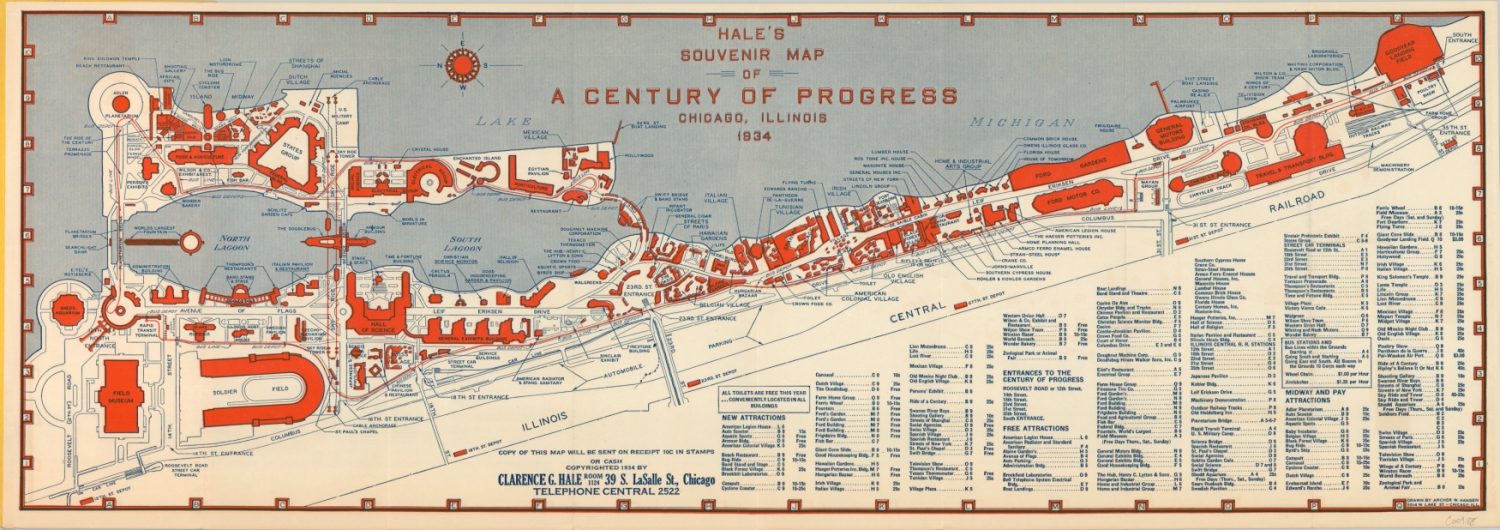

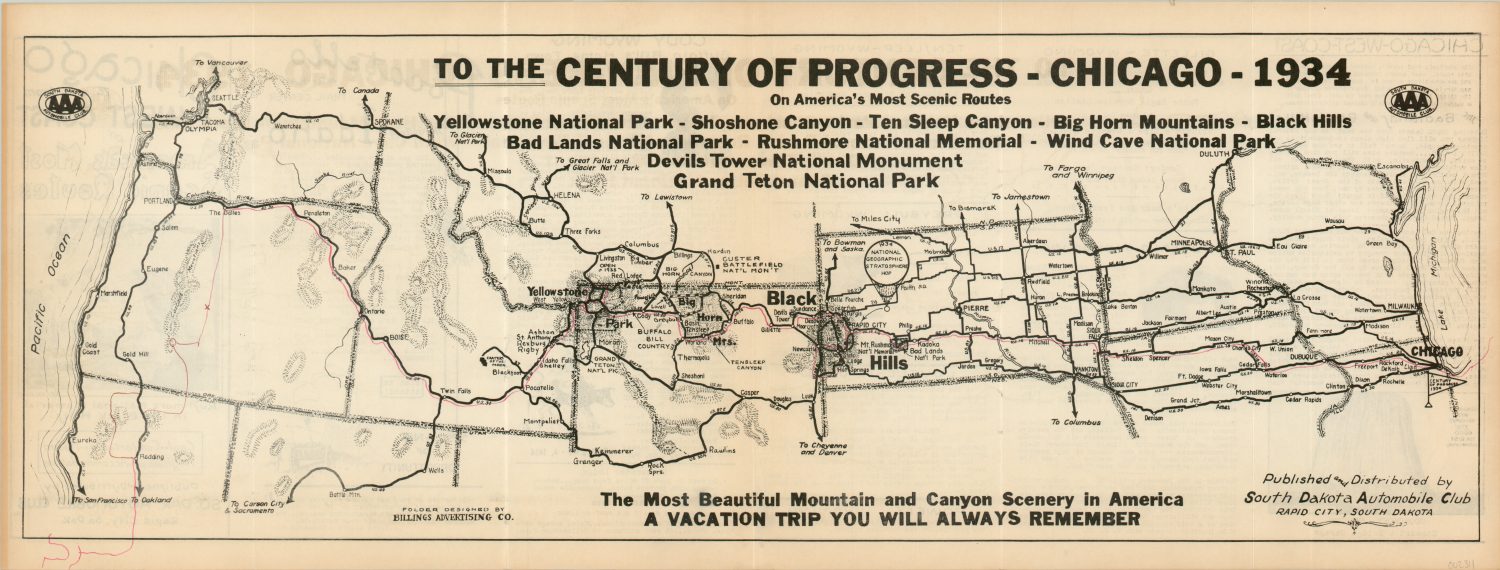

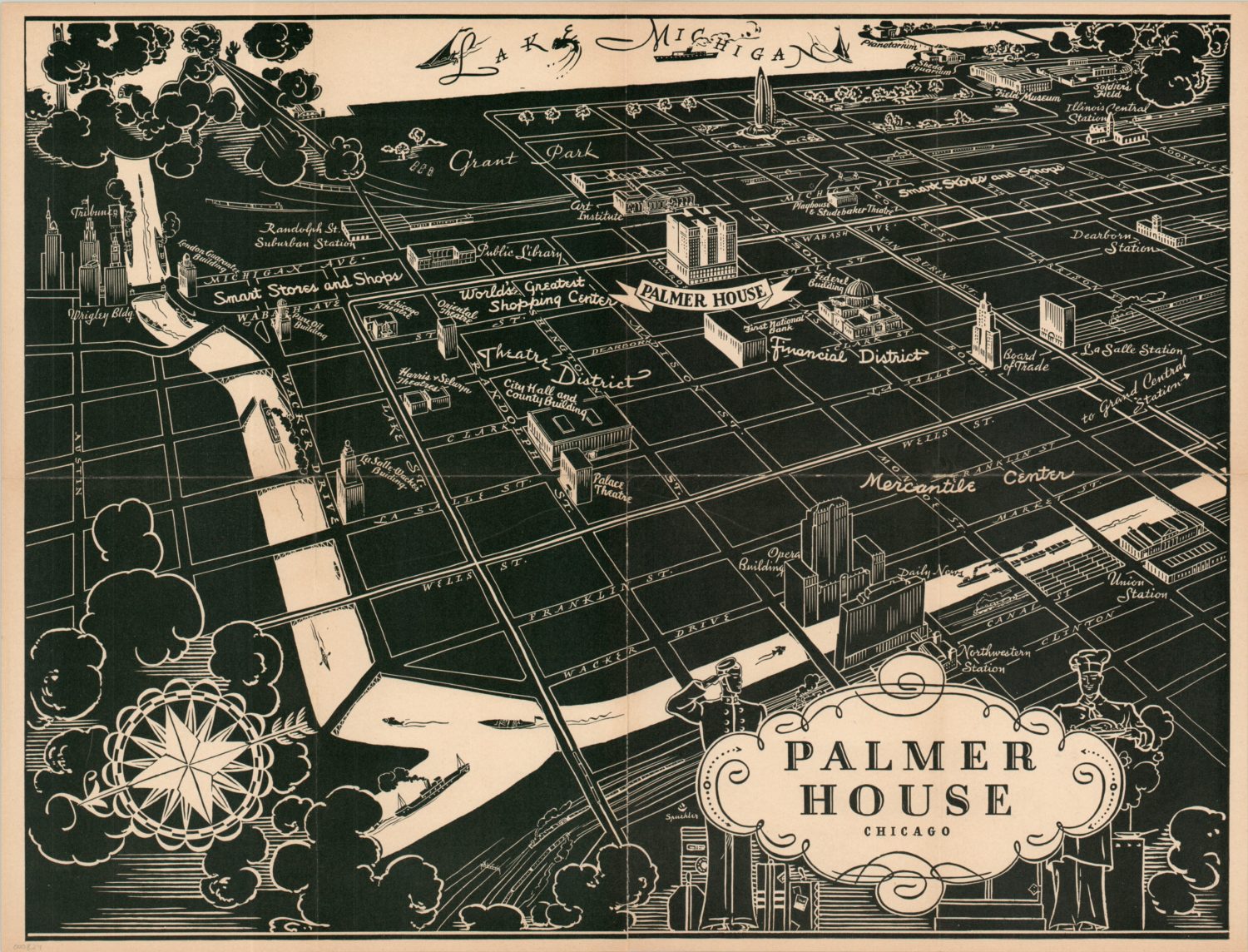

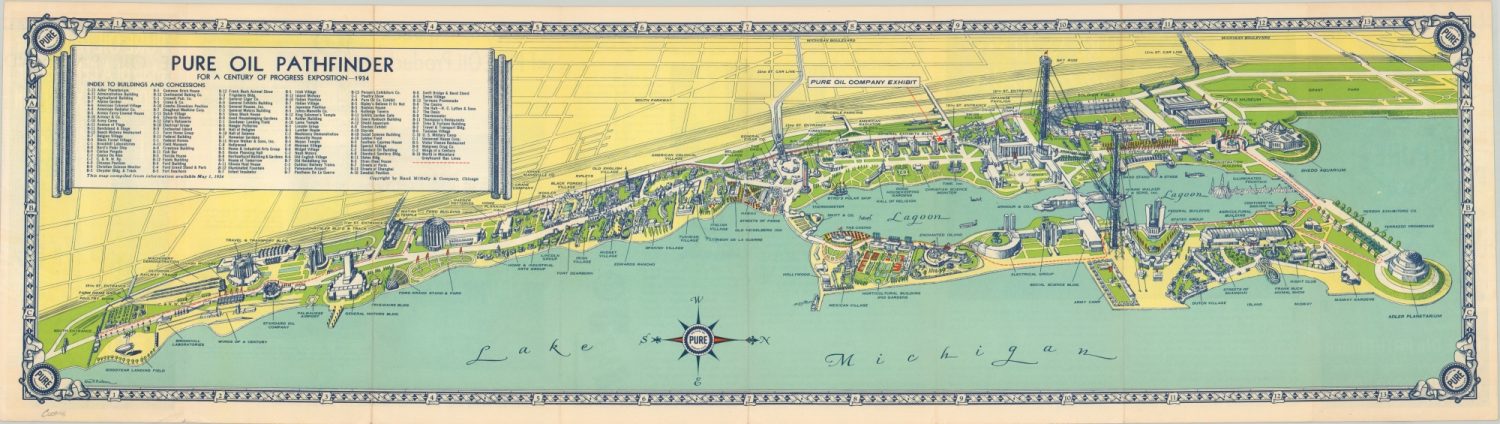

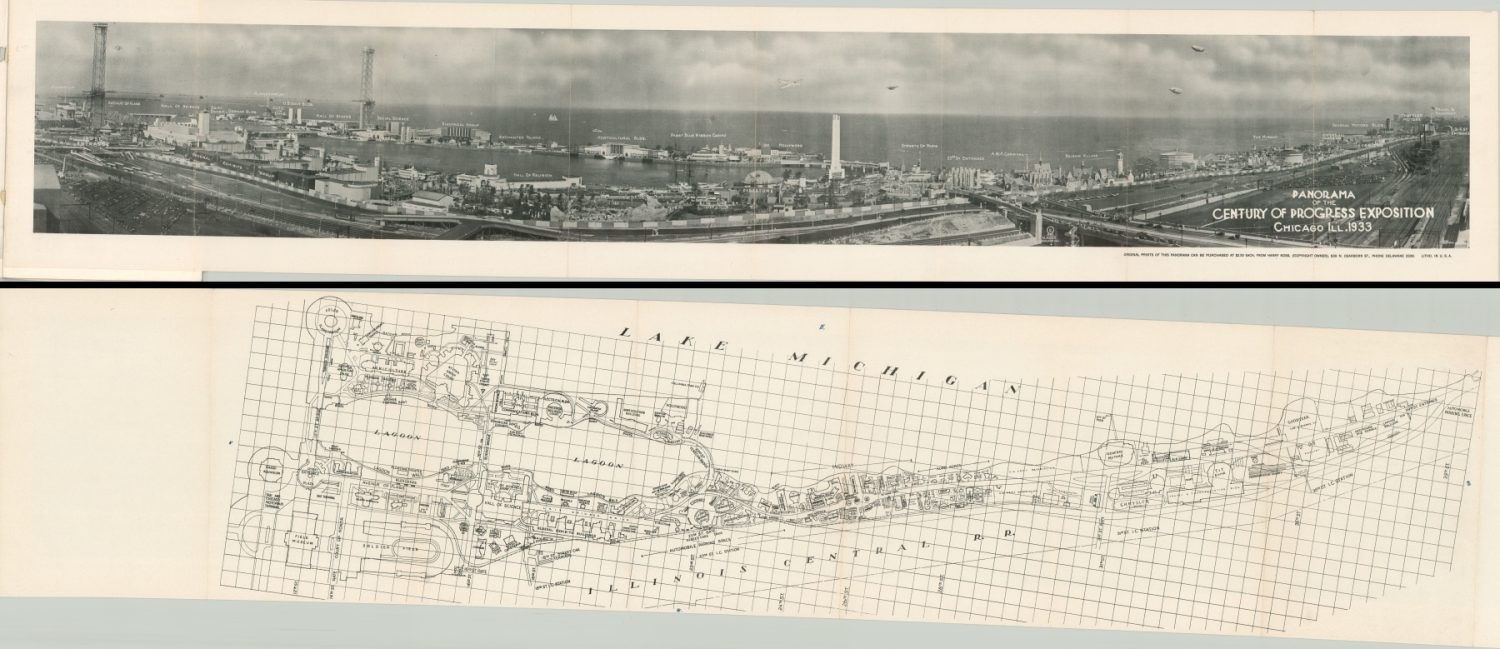

Chicago had exploded from approximately 350 residents in 1833 to nearly 3.5 million in 1933. Despite the tremendous growth, the city was devastated by the Great Depression. Rampant unemployment led to ‘Hoovervilles’ springing up in the early 1930s, and hunger and poverty were commonplace. Organizers of the 1933 Century of Progress, the city’s second World’s Fair, hoped the event would be a beacon of hope in the darkness. A happier future, enabled by cooperation between technology, business, and government, was encapsulated by the motto, “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Adapts.”

This attitude was reflected in the modernist architecture of the buildings, colored in vibrant hues to create a Rainbow City that contrasted with the White City of the Columbian Exposition. The latest in transportation, entertainment, and culture were juxtaposed against scenes highlighting Chicago’s past. Nearly two dozen corporations constructed official exhibits, greatly expanding on the levels of consumerism displayed at the prior fair. The Midway made another appearance, and thrilling attractions like the Sky-Ride provided endless amusement, for a price.

The exposition proved so popular that it was extended into a second year, and would ultimately see nearly 40,000,000 visitors as well as draw a profit – the greatest measure of success to the organizers. Although its impact on the city today is far less obvious than the Columbian Exposition; the expansion of Northerly Island, a number of monuments (including the controversial Christopher Columbus statue), and the opening of the Museum of Science and Industry all reflect permanent updates from the Century of Progress. Indefinable legacies include a brief window of escape from the Great Depression and a hope in technology that would come to define much of America’s concept of ‘progress’ in the coming years.

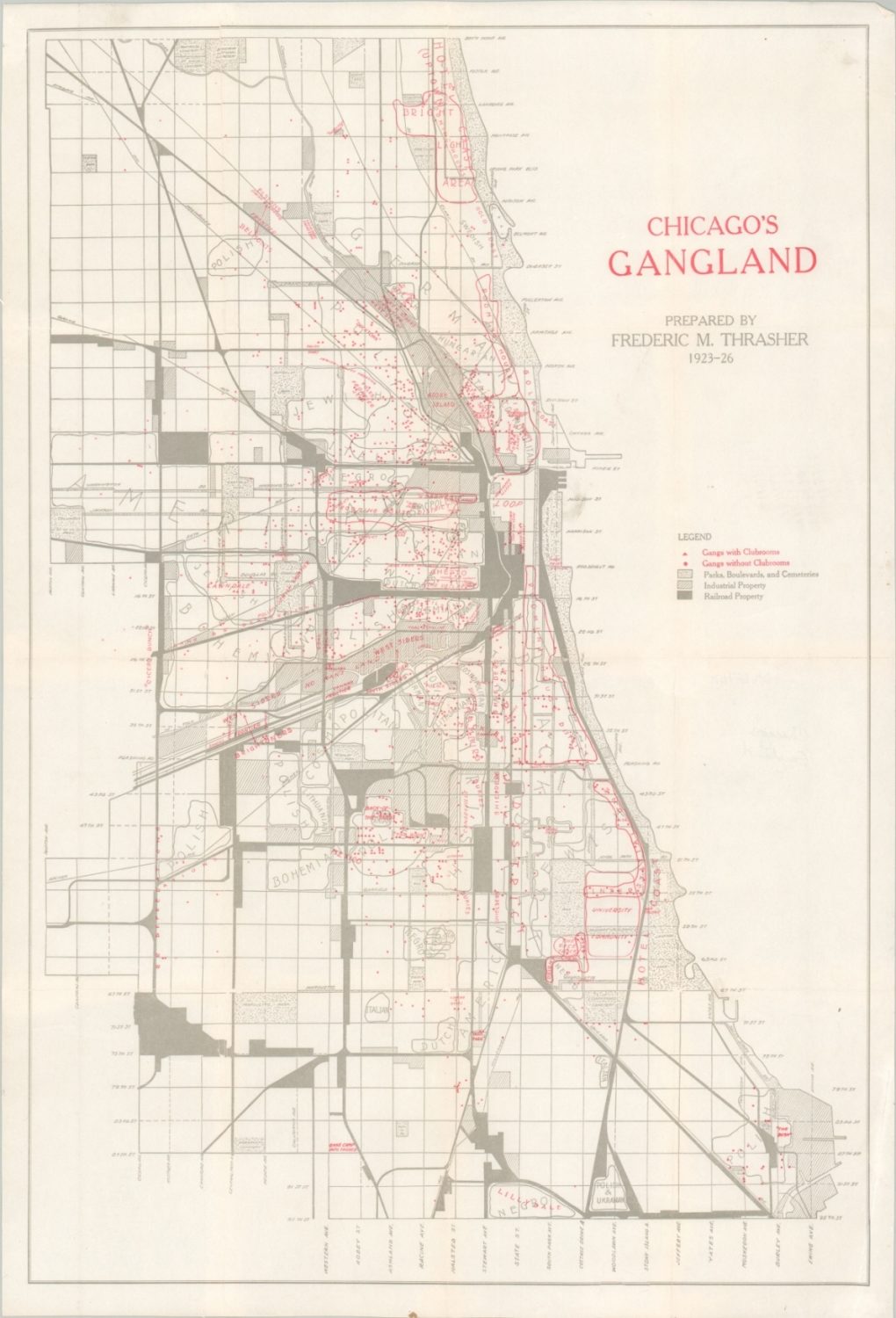

Using the Land

From the first manuscript maps made by French explorers, there was intent to use the land around Chicago for a variety of purposes. Economic gain, religious conversion, and military expansion were just a few of the motivating factors behind the region’s early non-native settlement. The first will forever be present, but the latter two were largely replaced by recreation, commercial development, and streamlining transportation.

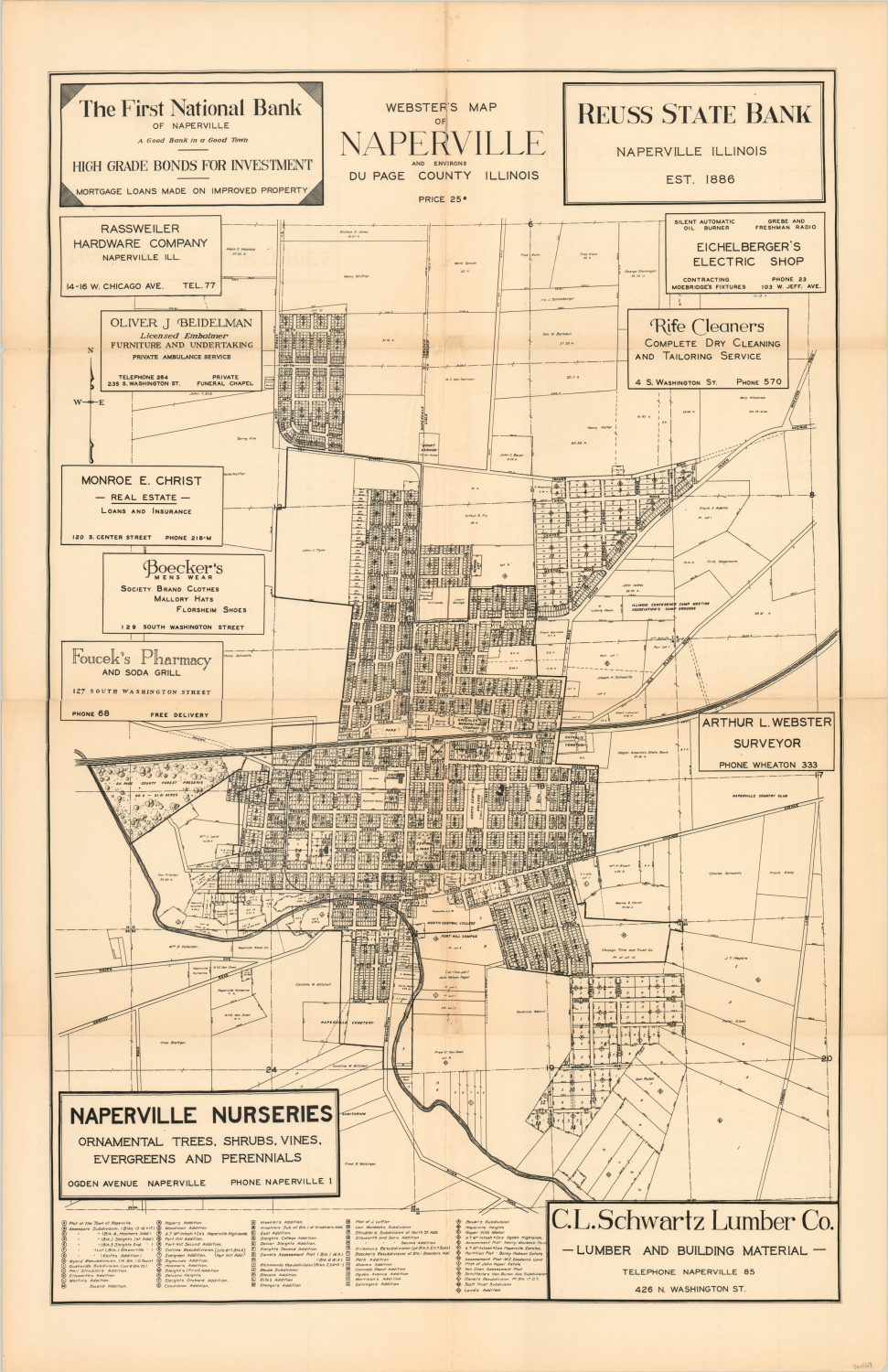

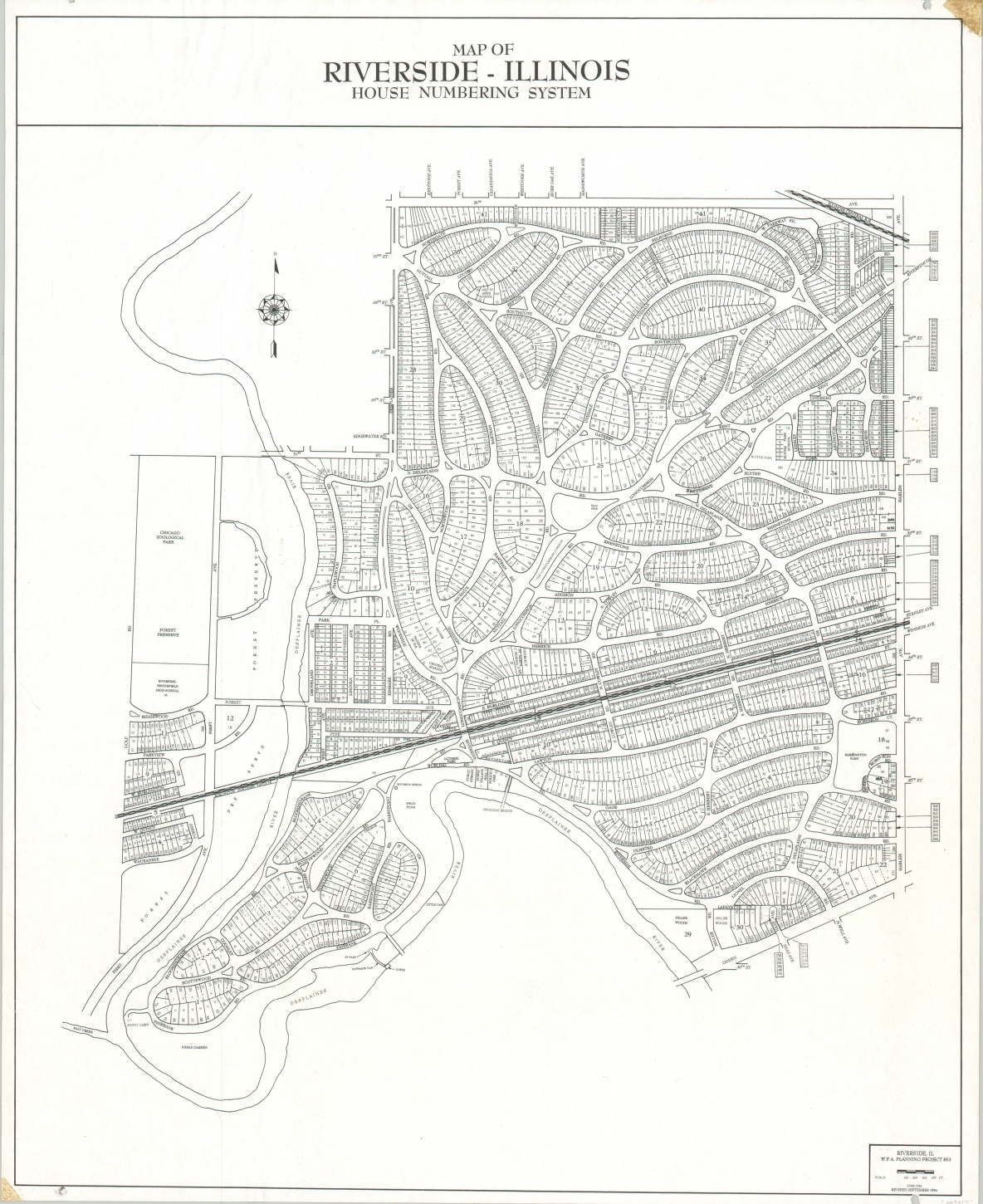

These maps of the city and surrounding area represent just a few of the many ways in which the land was mapped and used by residents, politicians, and businesses. The physical footprints of people and buildings are constantly changing, and maps are an effective way to capture specific elements at a particular time and place.

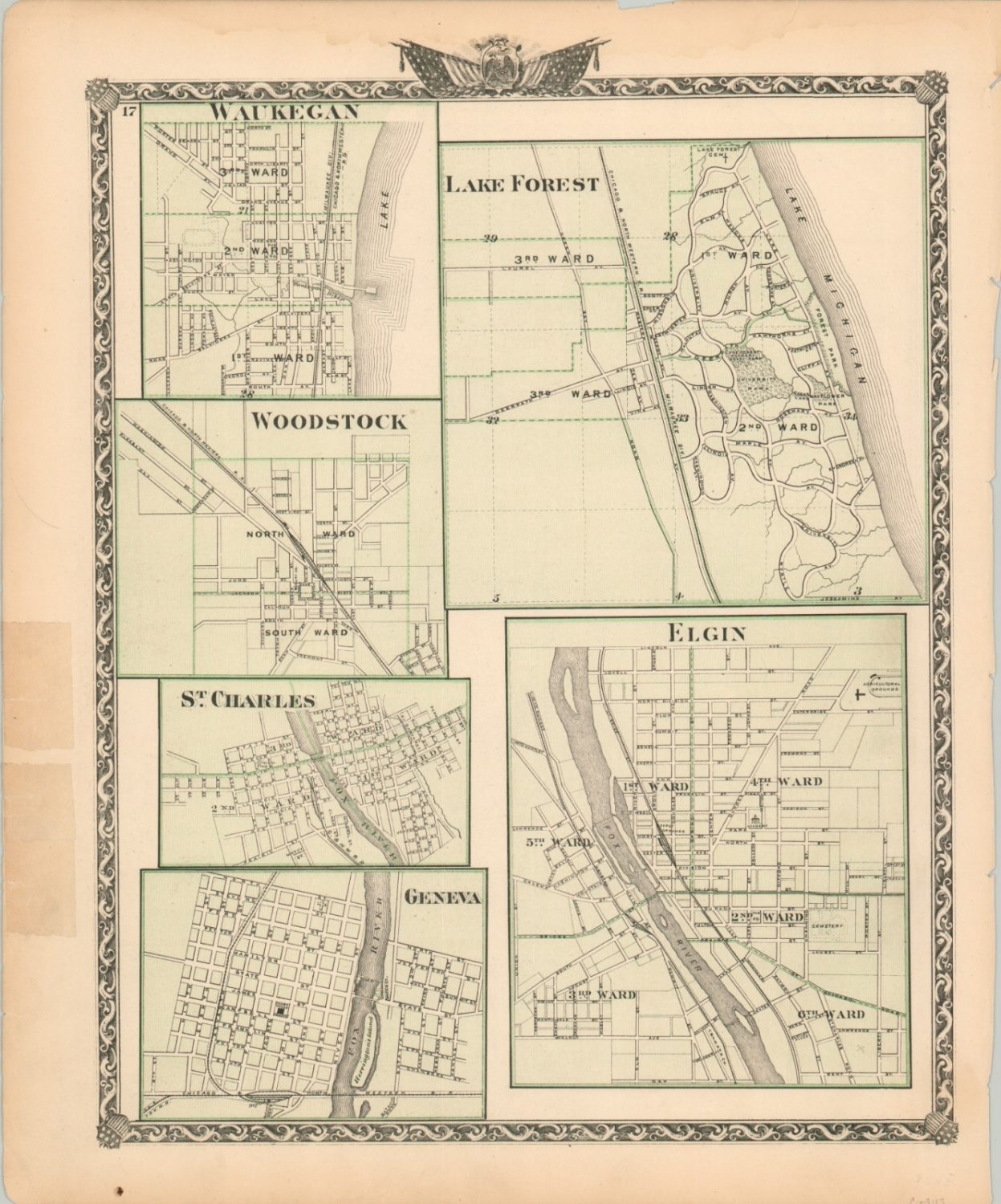

The ‘burbs

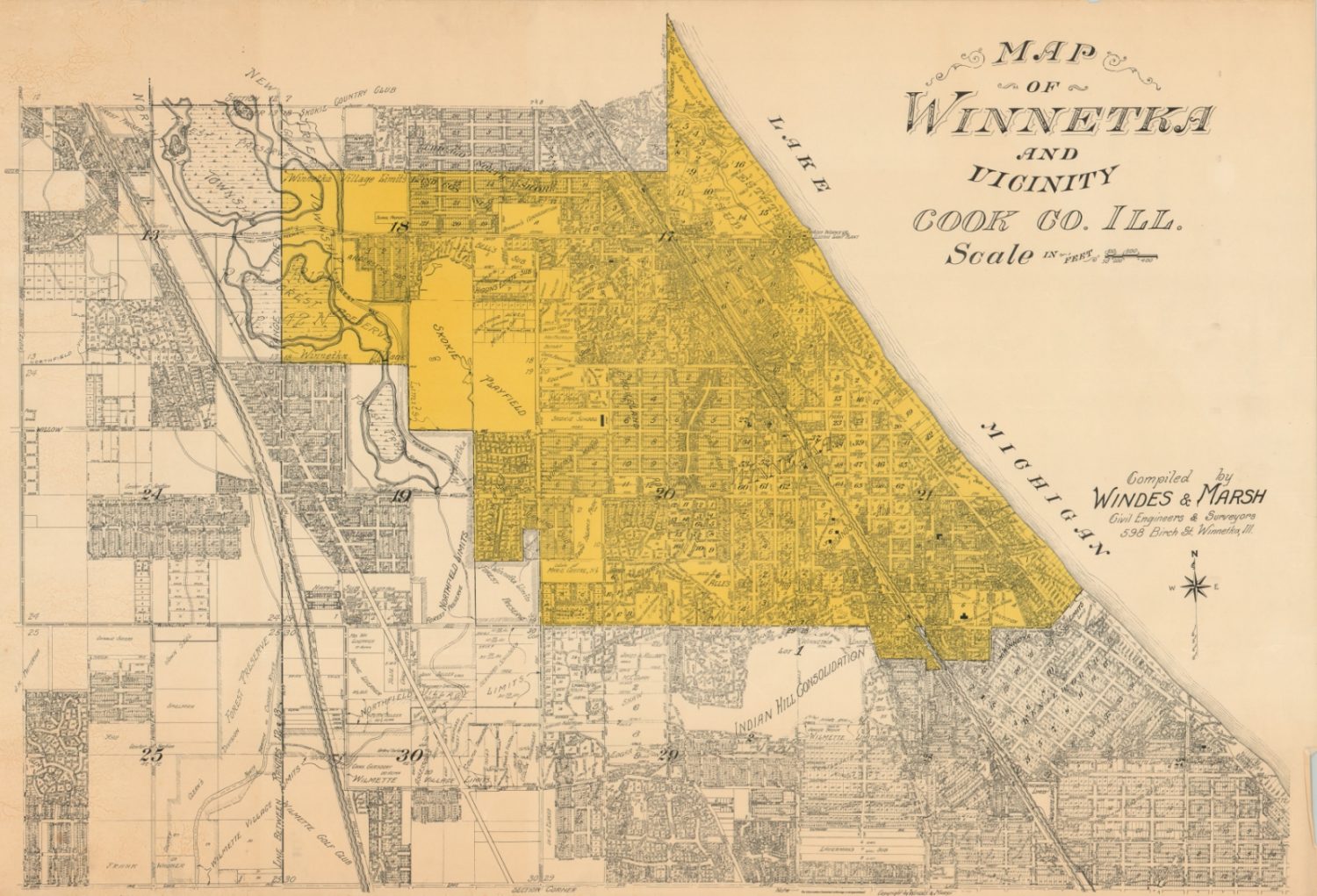

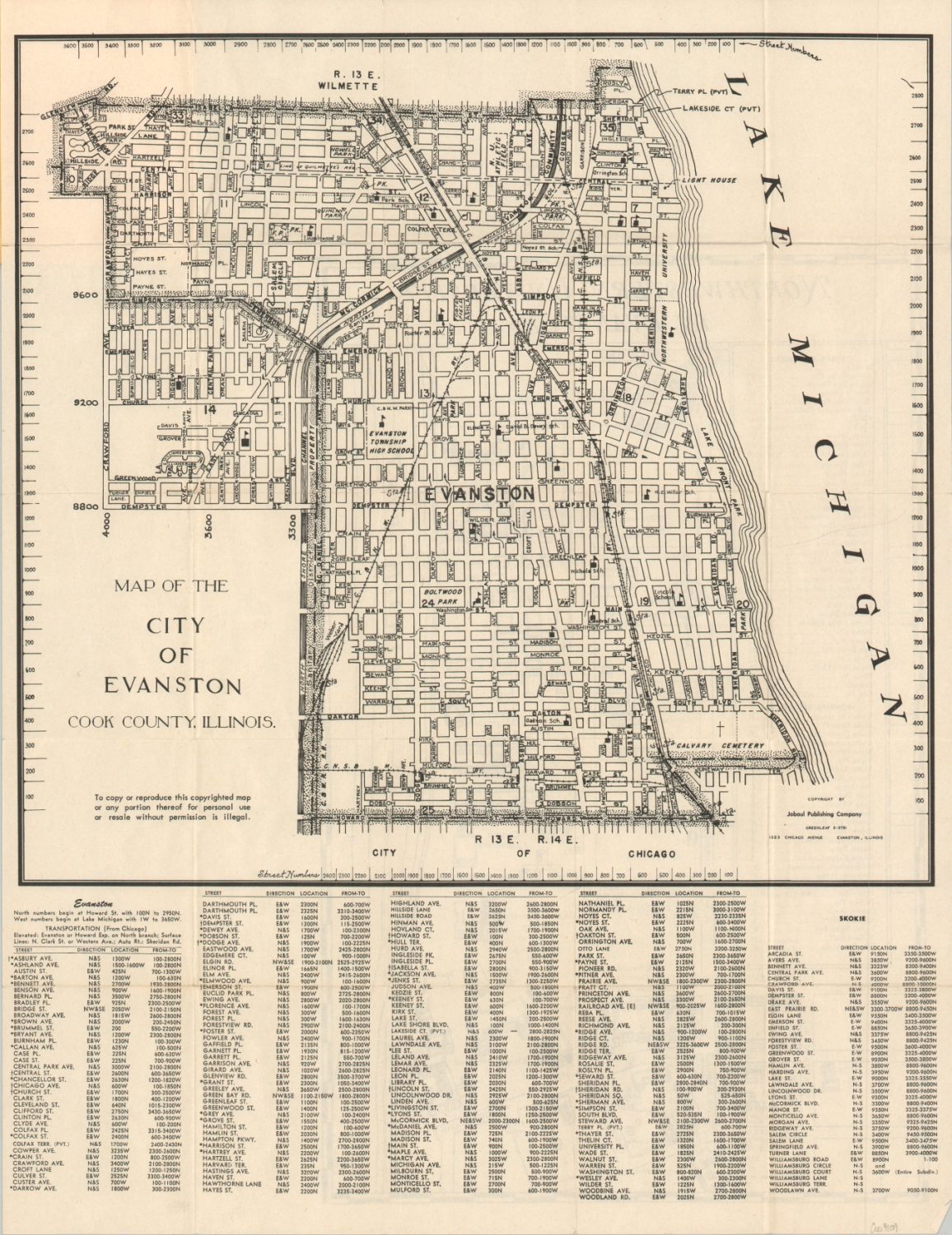

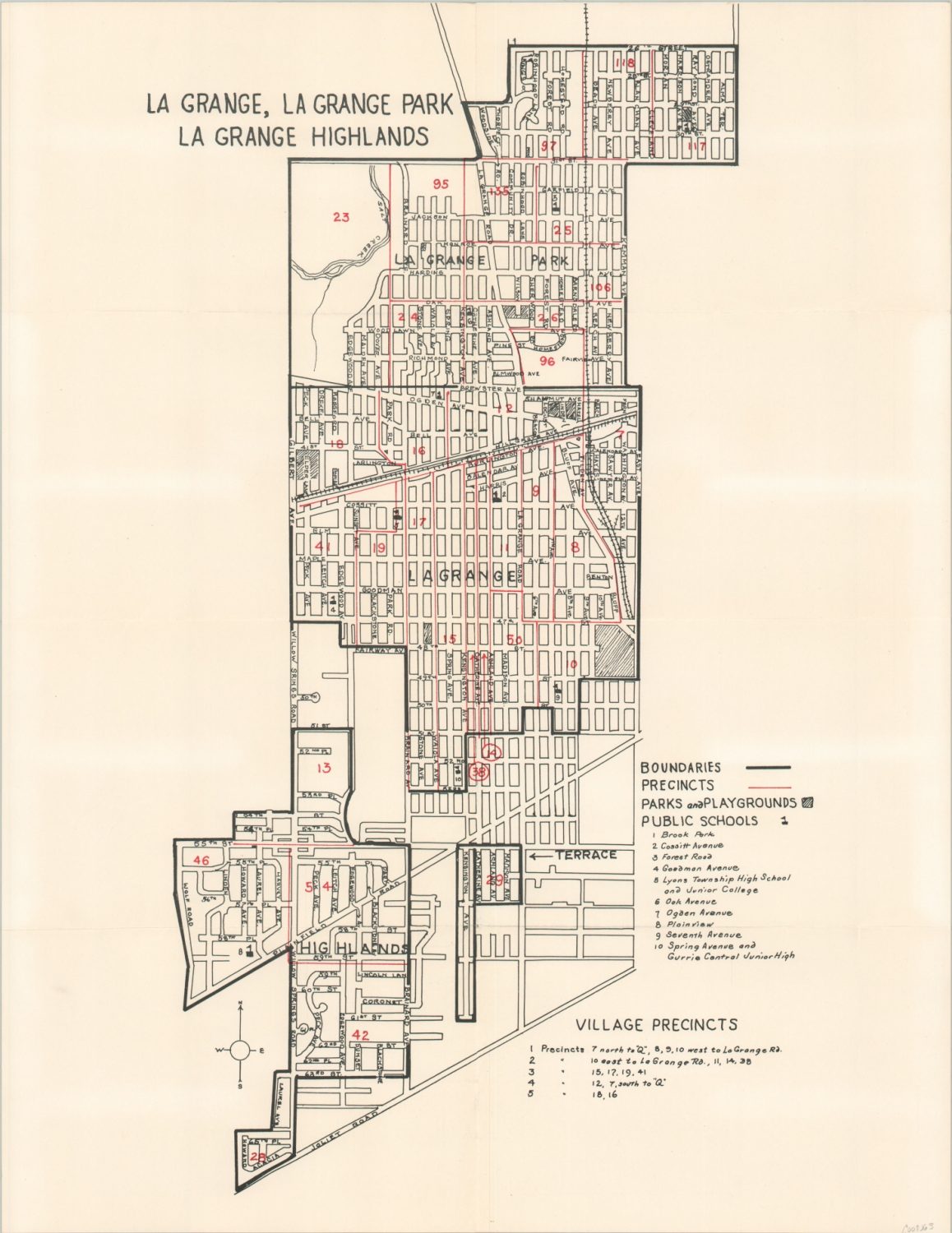

Chicagoland, The District, Heart of America, The 312 – nicknames for the Greater Chicago Metropolitan Area abound. And many from beyond that will still claim home to the Windy City, a powerful reflection on the association between the suburbs and urban center. The relationship is often a rocky one, both historically and today, but Chicago’s suburbia contributed significantly to its spectacular rise during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

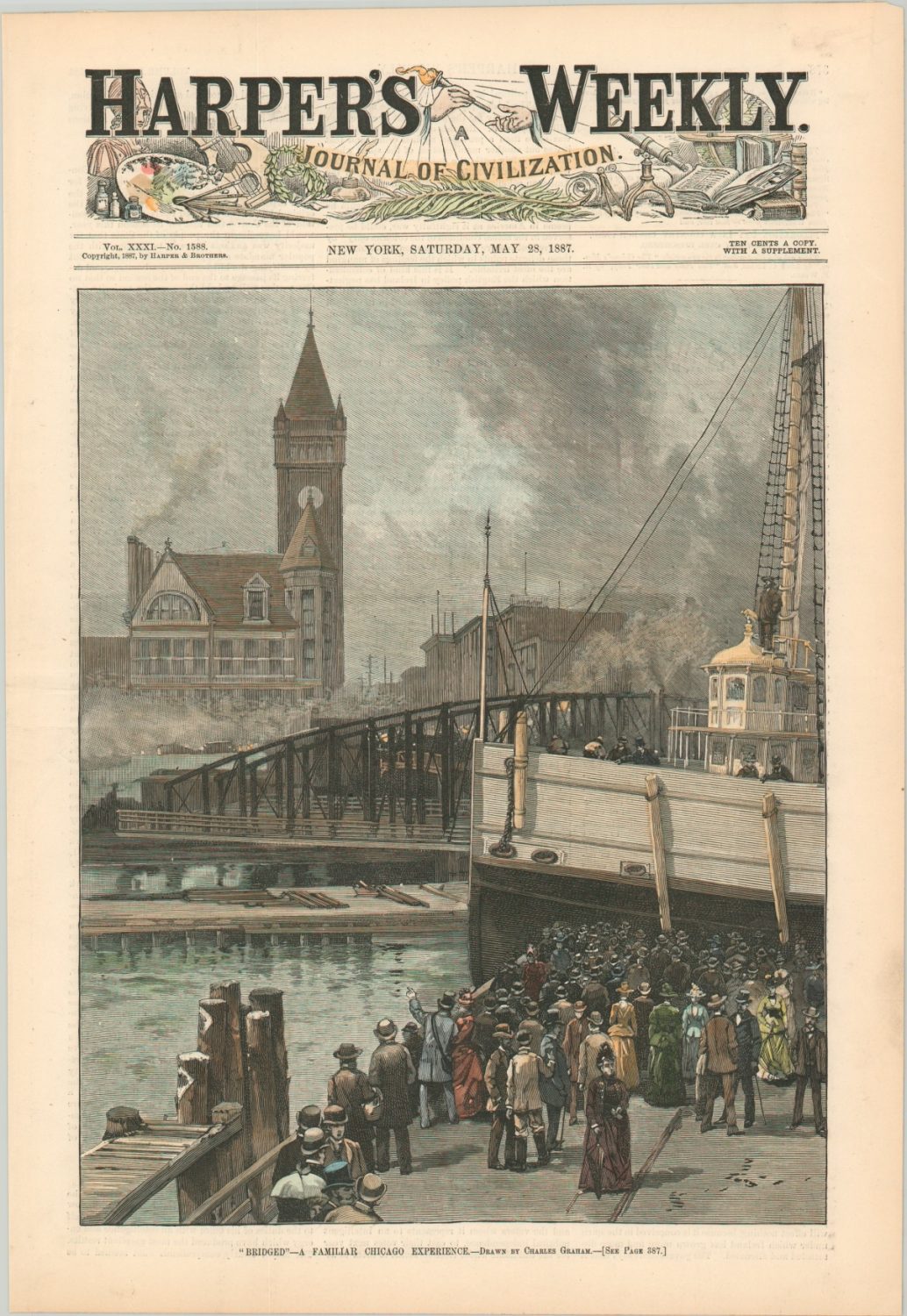

The Chicago River was the initial catalyst for growth outside the city, with several industries and small villages dotting the banks to the north and south in the mid-1850s. Plank roads further increased accessibility to nearby settlements, allowing for the easy transportation of people and goods to Chicago’s markets. Bridges were also a critical component in the development of the immediate surroundings, especially on the North Side, as the river was a hindrance to land-based traffic. Temperance movements, class, and various ethnic groups were also pivotal in shaping community identities.

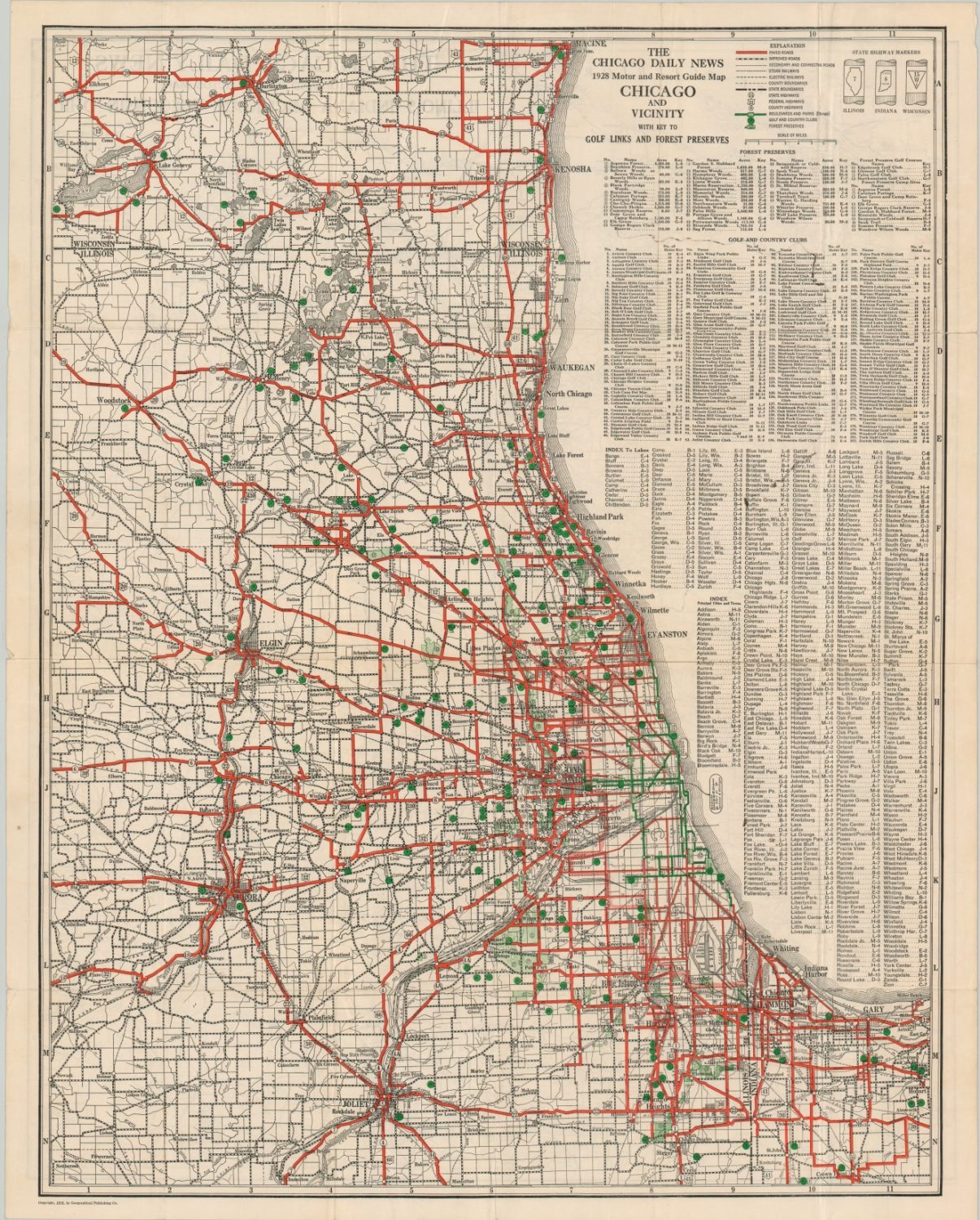

Though each suburb’s history is unique, the development and arrival of the railroad played a critical role in nearly every one. Steam railroads and electrified streetcars lines accelerated the trends mentioned above, creating a variety of industrial towns, agricultural communities, and residential districts connected by an ever-expanding network of iron rails. Recreational opportunities abounded with local attractions like parks, horse tracks, lakeside retreats, and even cemeteries drawing visitors from across the region.

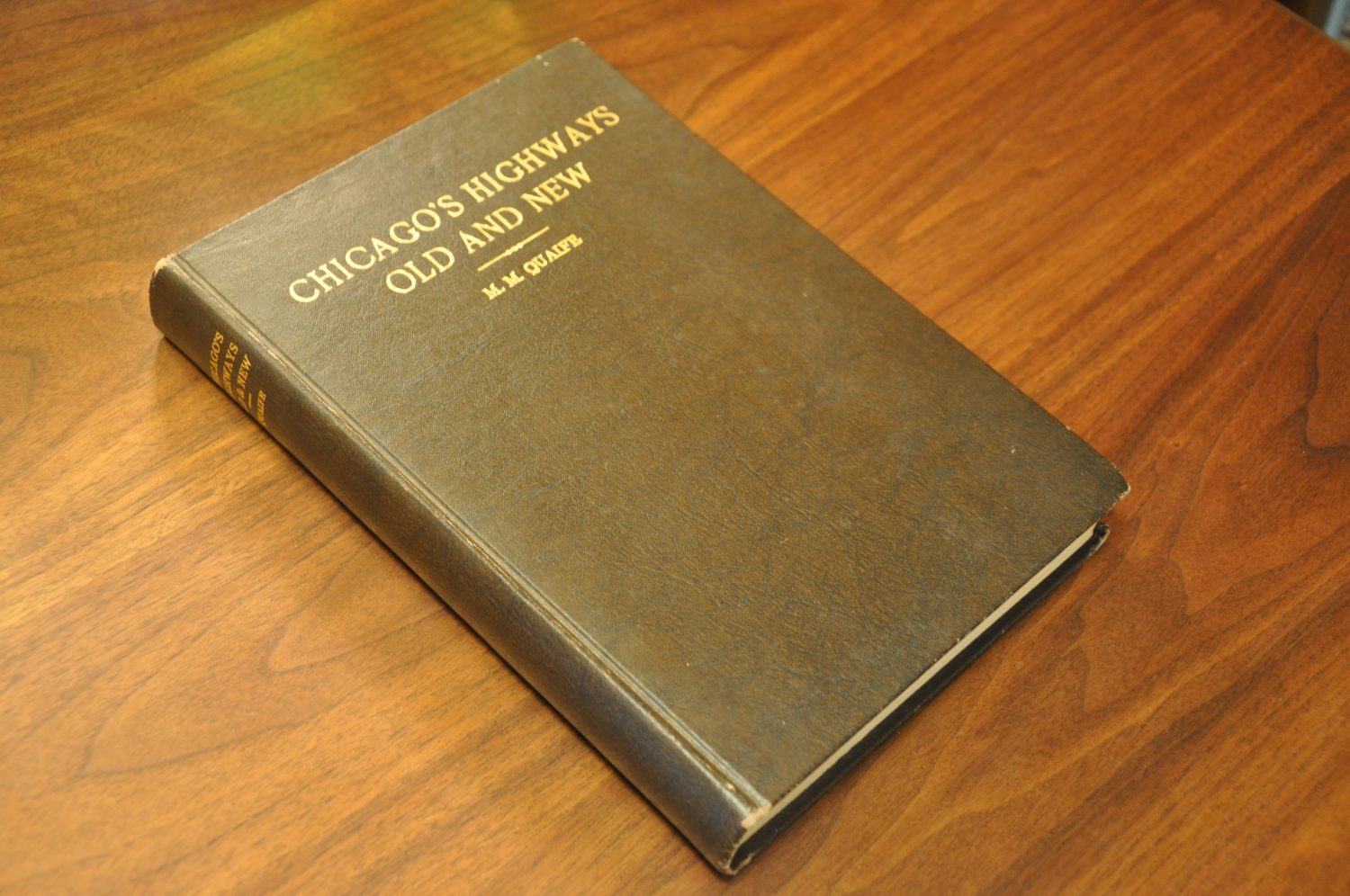

Transportation

As reflected above, the role of transportation has been pivotal to nearly every aspect of Chicago’s history and growth. Trails blazed by Native Americans were used by non-native settlers and formalized with wooden boards elevated above the prairie grasses and mud. (Milwaukee Avenue is one such example.) Fees were often charged to use such routes – our modern-day tollways were by no means the first. Waterborne traffic along the river and Lake Michigan not only facilitated the earliest exploration of the region, but also the export of commodities from farms, mines, stockyards, and mills across the Midwest.

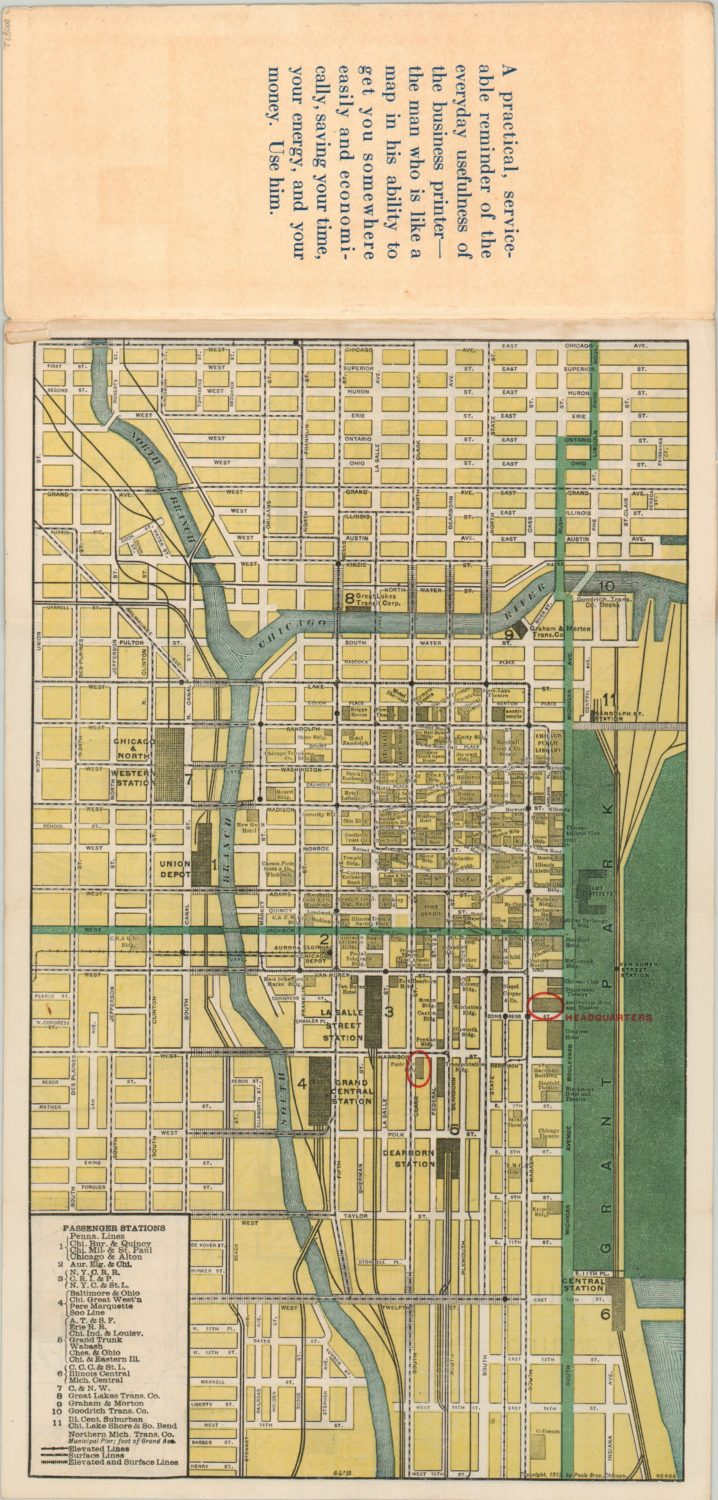

The arrival of both the first railroad (The Galena & Chicago Union) and the opening of the Illinois and Michigan Canal in 1848 marked a monumental year in Chicago’s history. The volume of trade increased exponentially as a result, and the city’s future as a commercial and transportation hub to the American West was permanently secured. Workers on these projects, and others, swelled the population and contributed further to expansion.

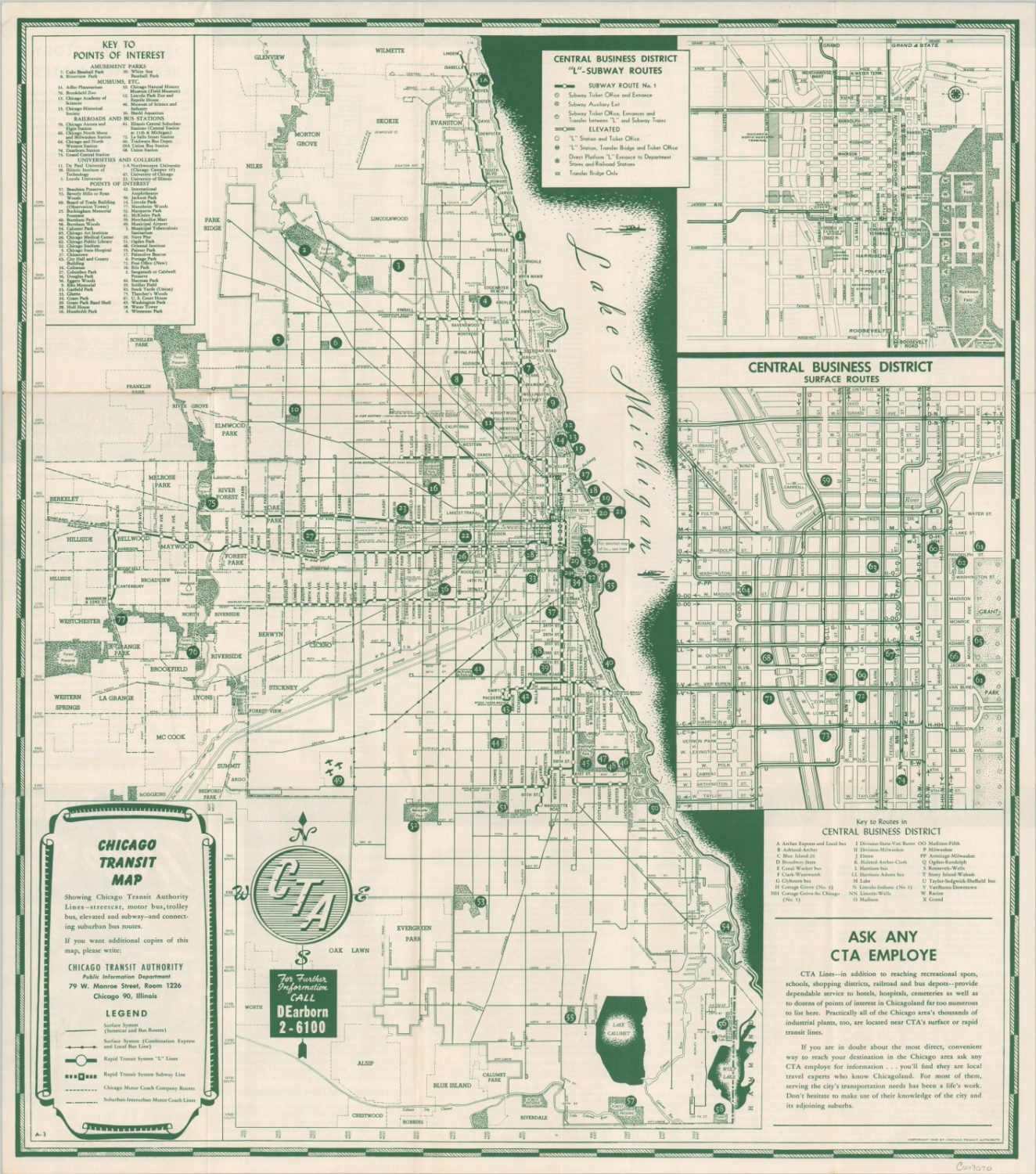

No transportation category would be complete without a number of different transit maps that capture the development of Chicago’s primary commuter arteries; including the State Street subway, streetcar lines, the L, and more. The establishment of the Chicago Transit Authority, construction of the expressway system, and even the pedestrian experience are also explored in maps.

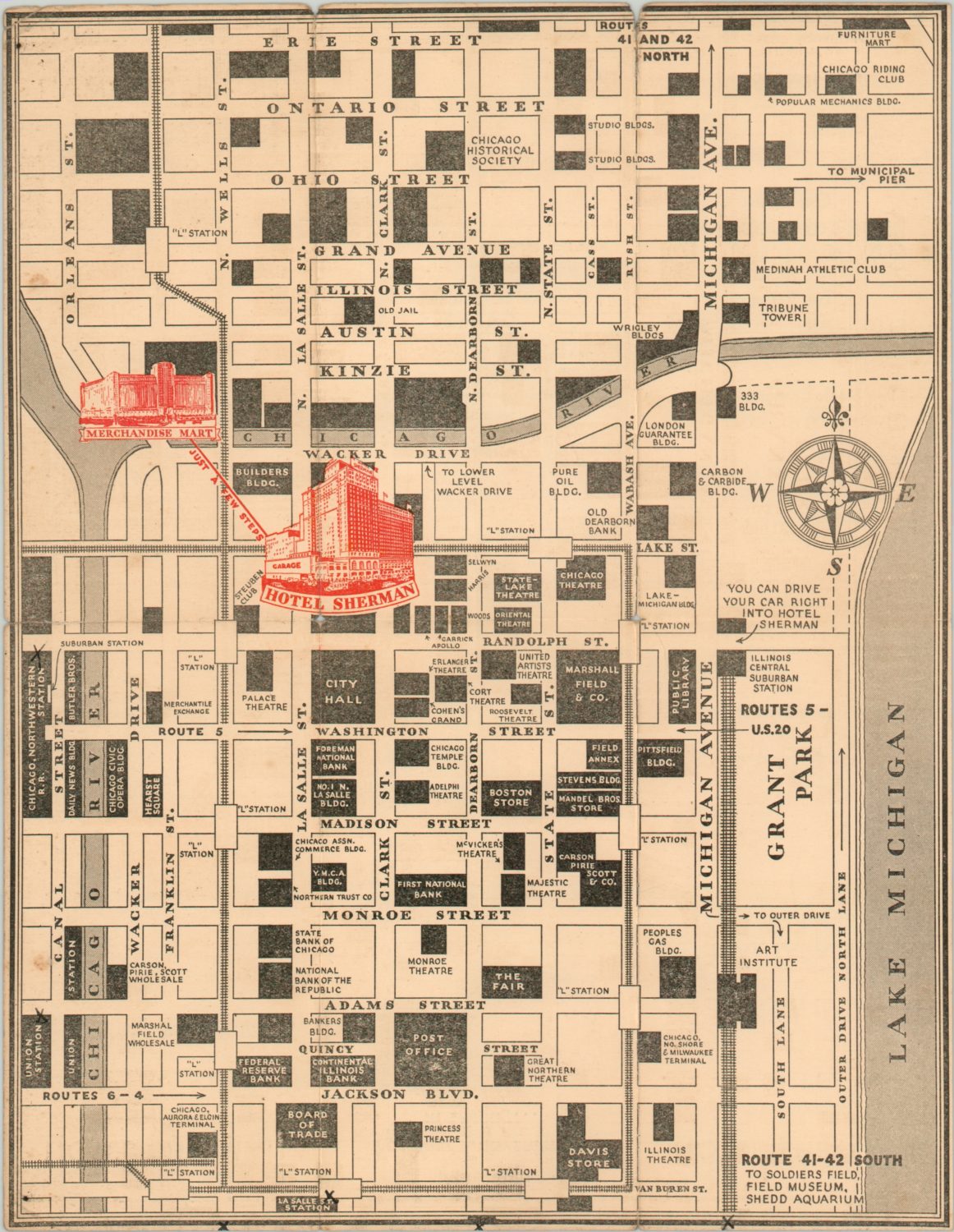

An Iconic Place

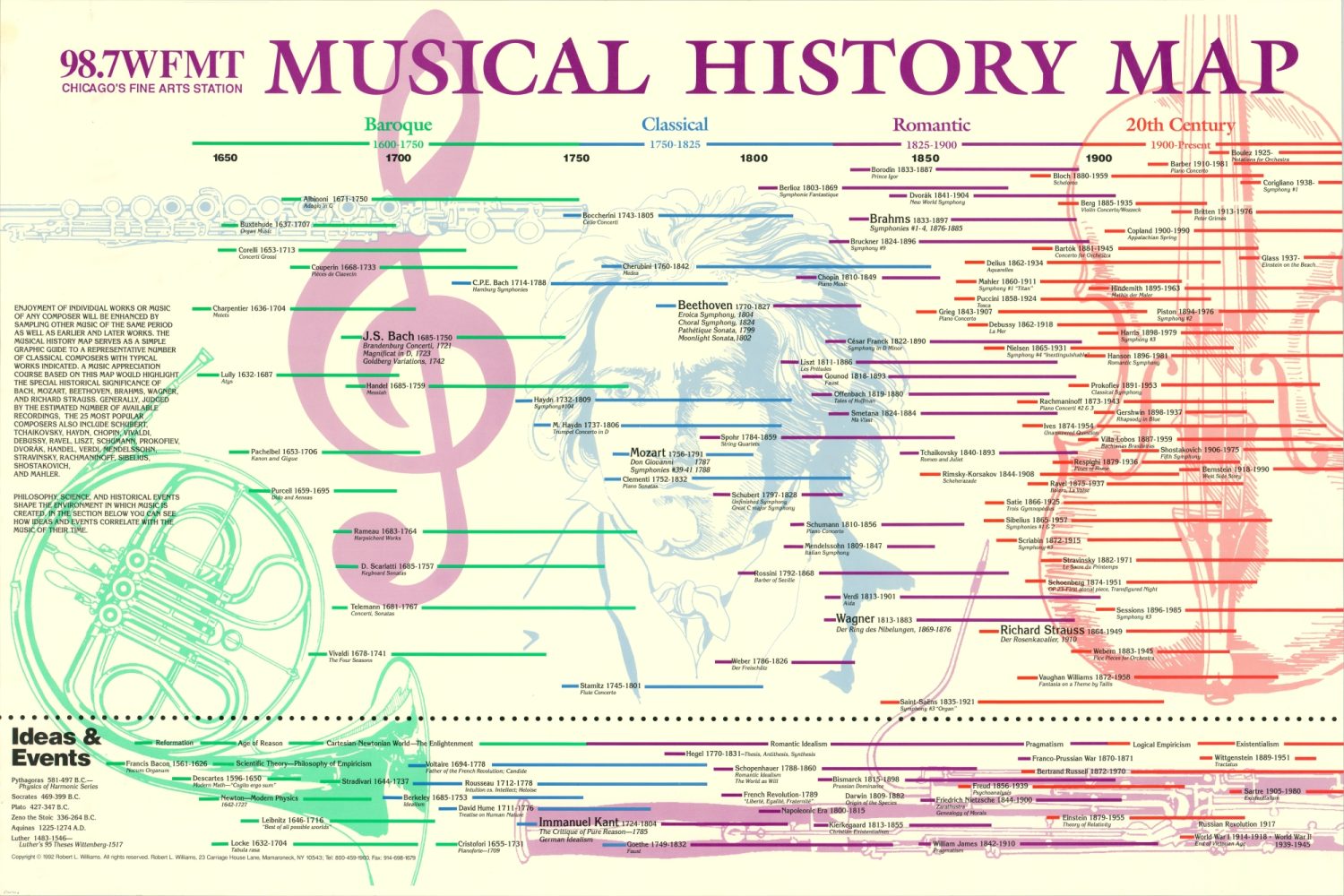

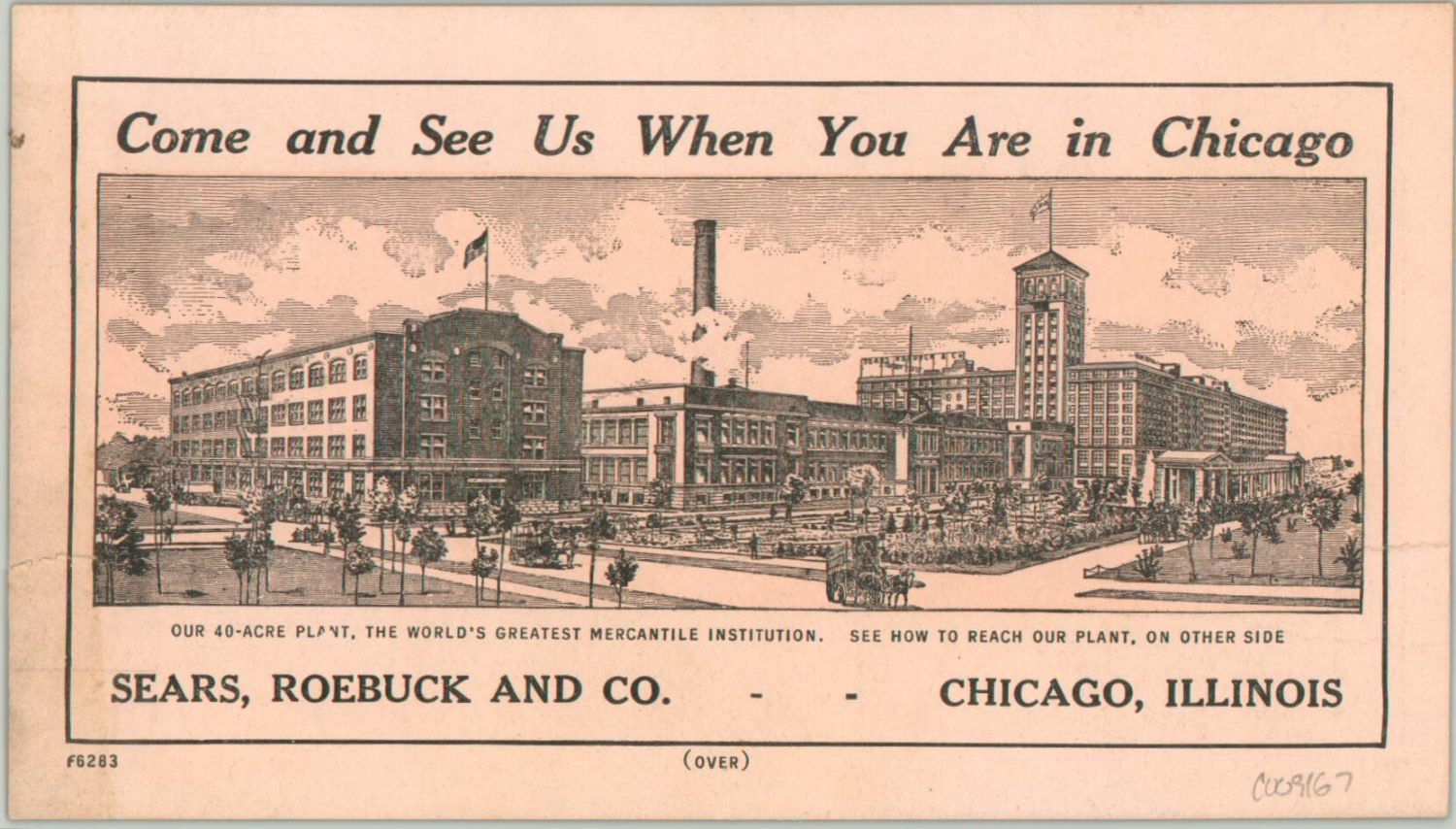

Though it’s possible I could have found other categories in which to place this material, I wanted to have a specific area dedicated to the wonderful ‘stuff’ that makes Chicago great. The city is known all over the world for its attractions and points of interest. Music, art, architecture, leisure, commerce, and industry are all celebrated as part of the rich offerings available to residents and visitors alike.

It was this tremendous variety and novelty that drew me to the city in the first place – not unlike those many thousands of attendees to the two World’s Fairs. The allure of mind-bogglingly tall buildings, museums and libraries containing the world’s rarities, and the best damn hot dogs on the planet will continue to be a powerful draw for myself and others.

In a little over a decade, we will have an opportunity to reflect on another century of progress, and I hope we share the same optimism and trust in the future as our predecessors. Although Chicago will forever remain an iconic place, much work remains to be done in order to restore its rightful status as America’s ‘Second City.’

Further Reading

Cronon, W. (1992). Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (Revised ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Grossman, J. R., Keating, A. D., & Reiff, J. L. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Chicago (1st ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Holland, R. A., & Danzer, G. A. (2005). Chicago in Maps: 1612–2002 (Second Printing ed.). Rizzoli.

Mayer, H. M., Wade, R. C., Holt, G. E., & Pyle, G. F. (1973). Chicago: Growth of a Metropolis (New edition). University of Chicago Press.

Miller, D. L. (1997). City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America (Reprint ed.). Simon & Schuster.

Smith, C. (2021). Chicago’s Great Fire: The Destruction and Resurrection of an Iconic American City. Grove Press.

Tribune, C. (1996). Chicago Days : 150 Defining Moments in the Life of a Great City (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.