To celebrate the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, I will be examining a new map from the war each month of 2020. In an earlier issue, we explored how the 5th Armored Division (The “Victory” Division) commemorated their campaign in the European Theater. But what about the U.S. Navy in the Pacific Theater? Today, we’ll be looking at a map detailing the experience of the U.S.S. Lexington (CV-16) – the oldest remaining fleet carrier in the world.

Construction on the ship began in 1941 as the U.S.S. Cabot, but word came during construction of the scuttling of the Lexington (CV-2) after taking heavy damage at the battle of the Coral Sea, and the drydock workers petitioned to have the name changed in honor of the first U.S. carrier lost in the war. She was commissioned in February, 1943 and after a short “shakedown cruise” in the Caribbean, the new Lexington headed through the Panama Canal to join the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

It’s here that I’d like to pause for a quick side bar. Shortly after passing through Panama, the Lexington experienced one of its first casualties of the war. Off the coast of Venezuela, one of the Grumman F4F Wildcats developed a leak during a training exercise and had to be ditched in the water. Neither the plane, nor its pilot, Nile Kinnick, was ever seen again.

Kinnick played football at the University of Iowa and won the 1939 Heisman Trophy. In his acceptance speech, Kinnick was grateful that he lived in America “where they have football fields instead of in Europe where they have battlefields.” He added “the football players of this country had rather battle for such medals as the Heisman Trophy than for such medals as the Croix de Guerre and the Iron Cross.” And yet, despite these thoughts, he volunteered for the Naval Air Reserve in 1941, writing “”There is no reason in the world why we shouldn’t fight for the preservation of a chance to live freely, no reason why we shouldn’t suffer to uphold that which we want to endure. May God give me the courage to do my duty and not falter.”

Kinnick’s story is emblematic of the youthful optimism and courageous heroism that inspired many of the sailors and aviators in the U.S. Navy. Yet the location of his tragic death didn’t even make it onto the map of the ship on which he served – a poignant reminder that commemoration is always imperfect, and nothing can adequately capture the collective sacrifice of the Allied forces during World War II.

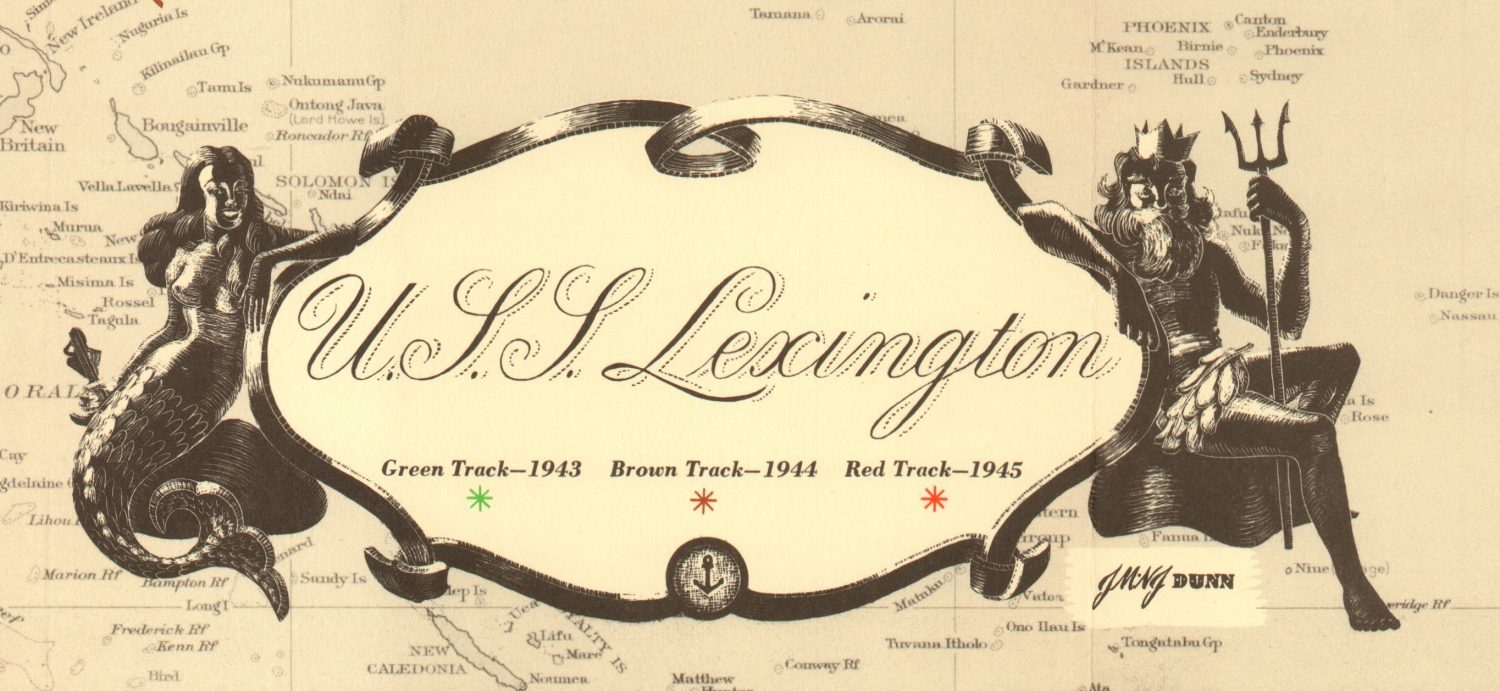

After cruising up the coast of South America and onward to Hawaii, the Lexington arrived at Pearl Harbor on August 9th, 1943. It’s here that the map picks up the action in the Pacific Theater, using dated lines of different color and composition to identify the various cruises of 1943, 1944, and 1945. Each route is overlaid on an enlarged prewar map covering the Pacific from east coast of China to northern Australia and the Hawaiian Islands. The author is unknown, but the signature JM – NJ Dunn just below the title cartouche likely indicates the map’s creator.

I won’t go into extensive detail about the operational history of the Lexington, but the carrier participated in nearly every major engagement against the Japanese. Bold black text highlights four particular memorable events for the crew; the strike on Tarawa, the Battle for Leyte Gulf, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, and entering the Bay of Tokyo. In addition, a dated list of most of the ship’s actions is provided in the upper right corner. These end at the middle of August, 1945, but the map was likely published in late September or early October, based on the entrance to Tokyo Bay and the hopeful proclamation of “California Here We Come!”

Despite the extensive index of accomplishments; the understated language and simple design of the map can almost be said to downplay the experience of the Lexington and her crew. During their 21 months of combat, the ship’s planes destroyed nearly 1,000 Japanese aircraft, sank or destroyed nearly a million tons of enemy cargo, and ferried thousands of troops back home to California and Hawaii. She was nicknamed the “Blue Ghost” by Japanese propaganda because she was reported sunk no less than four times and wore a slightly different shade of camouflage than most other U.S. ships.

Outside of a few decorative elements in the form of the naval-themed title cartouche, a handful of black & white illustrations and the navigational compass, the map is a “matter of fact” representation of the path of the U.S.S Lexington. Though the images vaguely reference combat, there is little to remind the reader of the harsh realities of war. No accidental deaths, kamikaze attacks, or actions of individual heroism are mentioned. There isn’t even a scale with which one could calculate the tremendous distance covered by the ship (over 25,000 miles, by my estimation). The inevitable outcome of victory is never questioned.

Fortunately, that victory did not mean the end of the U.S.S. Lexington. Though she was officially decommissioned in 1947, she was retrofitted as an attack carrier and recommissioned in 1955. After several additional tours in the Far East, she operated as a training carrier and, in 1980, would be come the first aircraft carrier with women stationed aboard. Today, she sits in the bay at Corpus Christi, Texas, where she functions as a museum ship and poignant reminder of the strategic importance of the aircraft carrier in the 20th century.