The tragic loss of Native American population and indigenous culture is one of the most calamitous effects from the gradual westward migration of settlers during the 19th century. A less visible, but no less gruesome, fate was shared by one of the most important components in the lives of the Plains Indians – the bison.

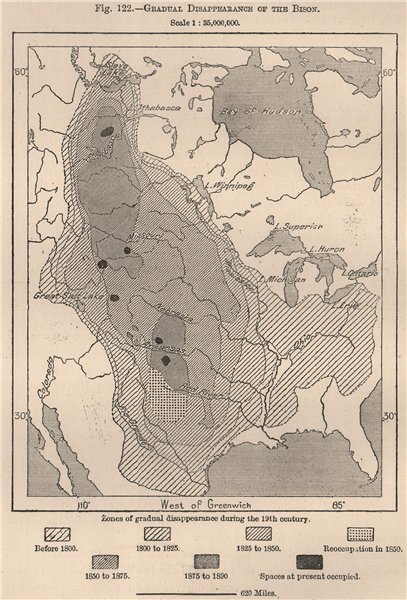

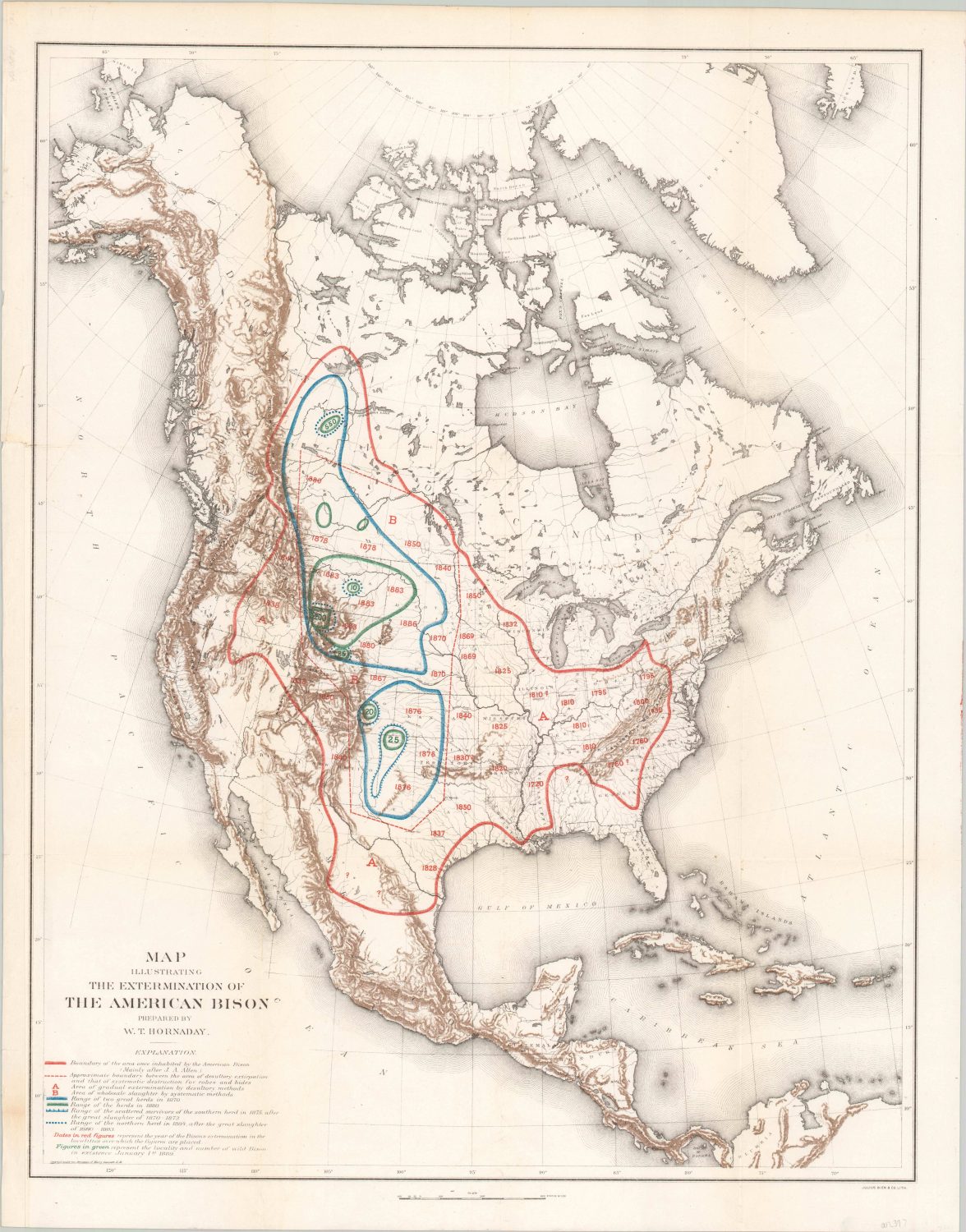

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, estimates ranging from between 30 and 75 million bison (also commonly known as buffalo) could be found roaming across over 1/3 North America. Their extent spread between the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachians, sometimes even approaching the Atlantic seaboard. Vast herds numbered in the thousands, with contemporary observers noting that a large herd could take hours (or even days) to pass by a particular spot.

The buffalo was an integral part of the culture and lifestyle of dozens of Native American tribes. Hunters would generally try to isolate old or weak individuals from the rest of the herd; often using upwards of six arrows to bring down one of the large beasts. A variety of other methods, such as stampeding off cliffs or into frozen water, were also employed. After a successful hunt, usually every part of the bison was used – meat, tendons, horns, fur, hide, bones – in a variety of utilitarian or spiritual purposes.

Though the largest animal in North America was particularly suited to the needs of the Plains Indians, it also held appeal to others. Hernan Cortez was the first European to actually see a bison (allegedly in Montezuma’s menagerie), but Cabeza de Vaca was the first to encounter one in the wild, and eat it. According to a later historian, he noted the utility of the ‘Mexican cow’ – with a rich robe and plentiful meat.

One of the earliest printed images of a bison, from Francisco López de Gómara’s La historia general de las Indias…

Over three hundred years later, it was largely these two factors that had seen the animal driven to near extinction across North America. Buffalo hunts were popular methods of feeding large groups; whether they were immigrants working on the Transcontinental Railroad, surveying parties, or soldiers on campaign. ‘Buffalo’ Bill Cody earned his moniker providing just such services, though he was decidedly more skillful at bagging bison than some of his contemporaries. With a company of just four men, Cody was able to kill over 4,000 animals during his short career working for the Kansas-Pacific Railroad.

Hunting and killing a bison is no easy feat. Adult males (bulls) can reach up to six feet at the shoulder and weigh as much as a ton. Females (cows) are slightly smaller, but can still easily weigh over 1,000 pounds. Though their eyesight is poor, they have a keen sense of smell and must be approached from upwind. Individuals are capable of running as fast as 35 mph and once a herd is spooked, the quarry is likely lost.

Even with a Sharps Model 1874 (a favorite rifle among hunters) that could shoot a .50 caliber cartridge nearly 2,000 feet per second, kill shots were rare. One estimate notes that, for every buffalo killed and harvested successfully, as many as four wandered off and died after being shot. Even then, the amount of meat hunting parties could transport often resulted in huge amounts of wastage (fans of the Oregon Trail game can relate).

Recreational hunting parties were often even worse offenders. The railroad brought ‘sportsmen’ who were keen to showcase their skills, with competitions held to see who could kill the most animals in a single outing. Groups of wealthy businessmen would rent out entire carriages, taking pop shots at any herds that were unfortunate to pass within range. In 1872, a Topeka newspaper writer noted, “I see no more sport in shooting a buffalo than in shooting an ox. Nor so much danger as there is hunting Texas cattle.”

Slaughter of Buffalo on the Kansas Pacific Railroad.

Reproduced from “The Plains of the Great West,” by Col. R. I. Dodge and included in Hornaday’s report.

Carcasses scattered the plains, but most often their skins had been taken. They were one of the most economically viable parts of the animal (along with the tongues, a delicacy), and ‘buffalo robes’ were in high demand around the world. Upon discovery of a large herd, commercial hunting parties could kill over a thousand animals in one day, if the herd was large enough. Piles of hides were stacked on wagons and ultimately transferred to rail cars for markets both east and west. The opportunity to make a quick buck brought thousands of these professional hunters out to the plains, especially after the Panic of 1873.

Though statistics can be difficult to determine with any precision, it’s likely that this form of commercial hunting was responsible for the most precipitous declines in bison populations across North America. Skins from cows and young males were particularly desirable – further exacerbating population issues. Diseases, drought, and loss of habitat also contributed to the tremendous loss between approximately 1840 and 1890, but there were other forces, more insidious than economic greed or natural events, that encouraged their final extinction.

Many within the U.S. Army (and government) saw the close relationship shared between the buffalo and various Native American tribes, and saw the former’s eradication as a way to control the latter. General Phil Sheridan, a prominent cavalry commander in the West, was alleged to have said, “Let them kill, skin, and sell, until the buffalo is exterminated. It is the only way to bring lasting peace and allow civilization to advance.”

Fortunately, not everyone shared in General Sheridan’s dream of ‘civilization’ and there were some proponents of protecting the remaining dwindling herds. After witnessing a bison hunt in 1843, James Audubon wrote, “This cannot last. Even now there is a perceptible difference in the size of the herds. Before many years, the buffalo, like the great auroch, will have disappeared. Surely this should not be permitted.”

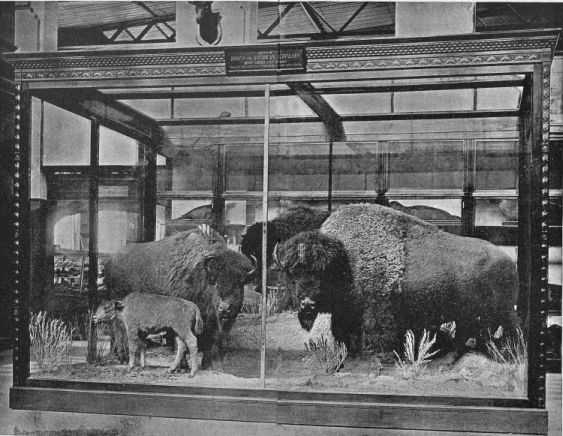

Few followed the prescient words of Audubon, or George Caitlin, or other contemporaries that warned against the loss of the buffalo. But several decades later, William T. Hornaday would take up the cause of bison preservation. Hornaday served as the taxidermist for the United States National Museum and was the first director of the New York Zoological Society.

Group of American Bisons in the National Museum.

Collected and mounted by W. T. Hornaday.

He first became interested in the creature after noting the meagre specimens available in the museum collections. After collecting data through correspondence and personal surveying, Hornaday published a report for the Smithsonian Institution in 1886 titled, The Extermination of the American Bison. This comprehensive account of the buffalo’s eradication details the history of its commercial exploitation and bleak future, encouraging the museum to collect as many specimens as possible while the few buffalo still roamed.

Hornaday’s efforts caught the eye of Theodore Roosevelt, who had earlier wrote “Never before in all history were so many large wild animals of one species slain in so short a space of time. The extermination of the buffalo has been a veritable tragedy of the animal world.” They both supported the establishment of the American Bison Society in 1905, which organized the first successful reintroduction of the bison onto American public lands two years later.

Their work continues to this day. Though the ABS was disbanded in 1935 (citing their work as complete), the organization was re-established by the Wildlife Conservation Society in 2005 to continue its work. There are over half a million bison roaming on public lands across North America as of 2020. On drives to southern Indiana to see my family, a small herd at Kankakee Sands helps to punctuate the otherwise boring trip down U.S. 41.

Sources:

“La historia general de las Indias, y todo lo acaescido enellas dende que se ganaron hasta agora. ; y La conquista de Mexico, y dela Nueua España” (1554). John Carter Brown Library. Brown Digital Repository. Brown University Library. https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:731268/

Dolin, Eric. Fur, fortune, and empire: the epic history of the fur trade in America.New York: W.W. Norton, 2011.

Guengerich, S. (2013). The Perceptions of the Bison in the Chronicles of the Spanish Northern Frontier. Journal of the Southwest, 55(3), 251-276. Retrieved April 20, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24394946

Hornaday, William T. The Extermination of the American Bison. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1889. Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17748/17748-h/17748-h.htm

King, Gilbert. “Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed.” Smithsonian Magazine, 17 July 2012, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/where-the-buffalo-no-longer-roamed-3067904.

Merchant, C. American environmental history: An introduction. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007.

SEHM, GUNTER G. “The First European Bison Illustration and the First Central European Exhibit of a Living Bison. With a Table of the Sixteenth Century Editions of Francisco López de Gómara.” Archives of Natural History, vol. 18, no. 3, 1991, pp. 323–32. Crossref, doi:10.3366/anh.1991.18.3.323.