Hello Map Enthusiast,

Although the world has slowed considerably as a result of COVID-19, Curtis Wright Maps carries on. We’re in the middle of a move to a larger space and continue to update the website regularly with new inventory. Stay tuned for further updates, and thanks for your ongoing support!

We’re also excited to carry on the monthly tradition of exploring different maps from WWII to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the war’s end. Today is particularly relevant, as May 8th is officially considered “V-E Day” (Victory in Europe), when Allied commanders accepted the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany.

Celebrations would ring out across the continent, but fighting in the Pacific Theater raged on. Allied bombers were constantly bombarding Japanese defensive fortifications, industrial regions and shipping while fighters maintained air superiority over much of the theater.

Japan’s inability to replace experienced pilots was one of several reasons they were losing the battle for the skies over the Pacific. Allied commanders better understood the strategic value of trained flyers and supported programs to increase survivability. Efforts to make safer and more reliable aircraft paid off, but casualties remained inevitable. However, just because a pilot was downed didn’t necessarily mean he was out.

MI9 was a department of the British Military Intelligence service that was established in December of 1939, in part, to help facilitate the return of pilots shot down over enemy territory. It was immediately apparent that one way to help accomplish this task was to distribute maps of the territory in which the airmen will be operating. It is here that Christopher Clayton Hutton, Technical Officer to the Escape Department, enters the story.

Over his six-year tenue at MI9, Hutton designed numerous mechanisms to help facilitate the escape of POWs, but he is likely best known for the development of the silk escape map. Originally designed to as part of an escape “package” that included fishing line, a compass and other survival tools, the map was printed on silk to help with durability (especially when wet), minimize noise and maximize compactness so it could be stored someplace discreet, like in the heel of a boot.

Hutton enlisted the assistance of the well-known Scottish mapmaking firm of John Bartholomew & Son, who agreed to waive all copyright claims and provide the cartographic data free of charge. Printing was a little trickier, especially when multiple colors were used, as they had a tendency to bleed and run. The British firm of Waddington Ltd. had experience printing theater programs on silk, and a partnership with MI9 ultimately led to the production of thousands of maps on silk, tissue, and rayon over the course of the war. (An interesting note: Waddington was the UK publisher of Parker Brothers’ hit board game Monopoly, and the firm would include maps inside of game boards for use by soldiers in POW camps.)

In late 1942, a small group of American intelligence officers met with members of MI9 to debrief on Britain’s ongoing efforts on escape and evasion tactics. Examples of silk maps were provided as part of the exchange. Both the U.S. Air Force (AAF) and the U.S. Navy (USN) saw the value in printing maps on fabric and worked directly with the Army Map Service (AMS) to find a suitable silk substitute. Eventually, a partnership with DuPont Corporation and Kaumagraph Company (experts in textile lithography) determined that acetate rayon would be an excellent candidate for its durability, resistance to shrinking and ink retention. Ultimately, nearly all U.S. escape maps would be printed on acetate rayon, making the name “silk map” somewhat of a misnomer.

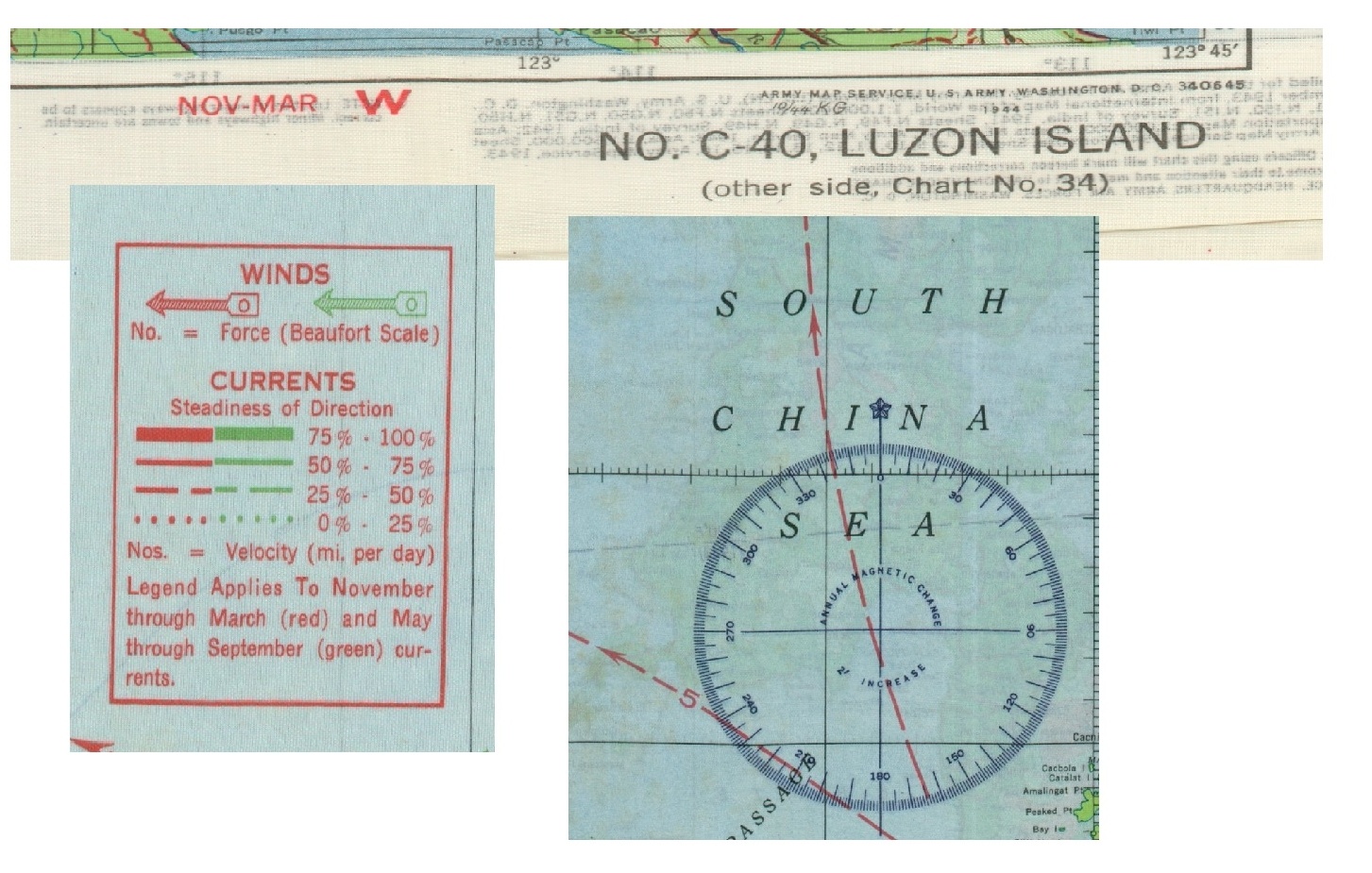

In August of 1943, the Army Map Service began full scale production of cloth maps, which continued at a frenetic pace through the end of the war (as many as 250,000 maps/month). Most printing was contracted to one of three firms, with the AMS overseeing the editing and design. Over 50 separate sheets were published, many of which were distributed in the hundreds of thousands. Each map was double sided, and contained as many as 7 colors, depending on the information presented.

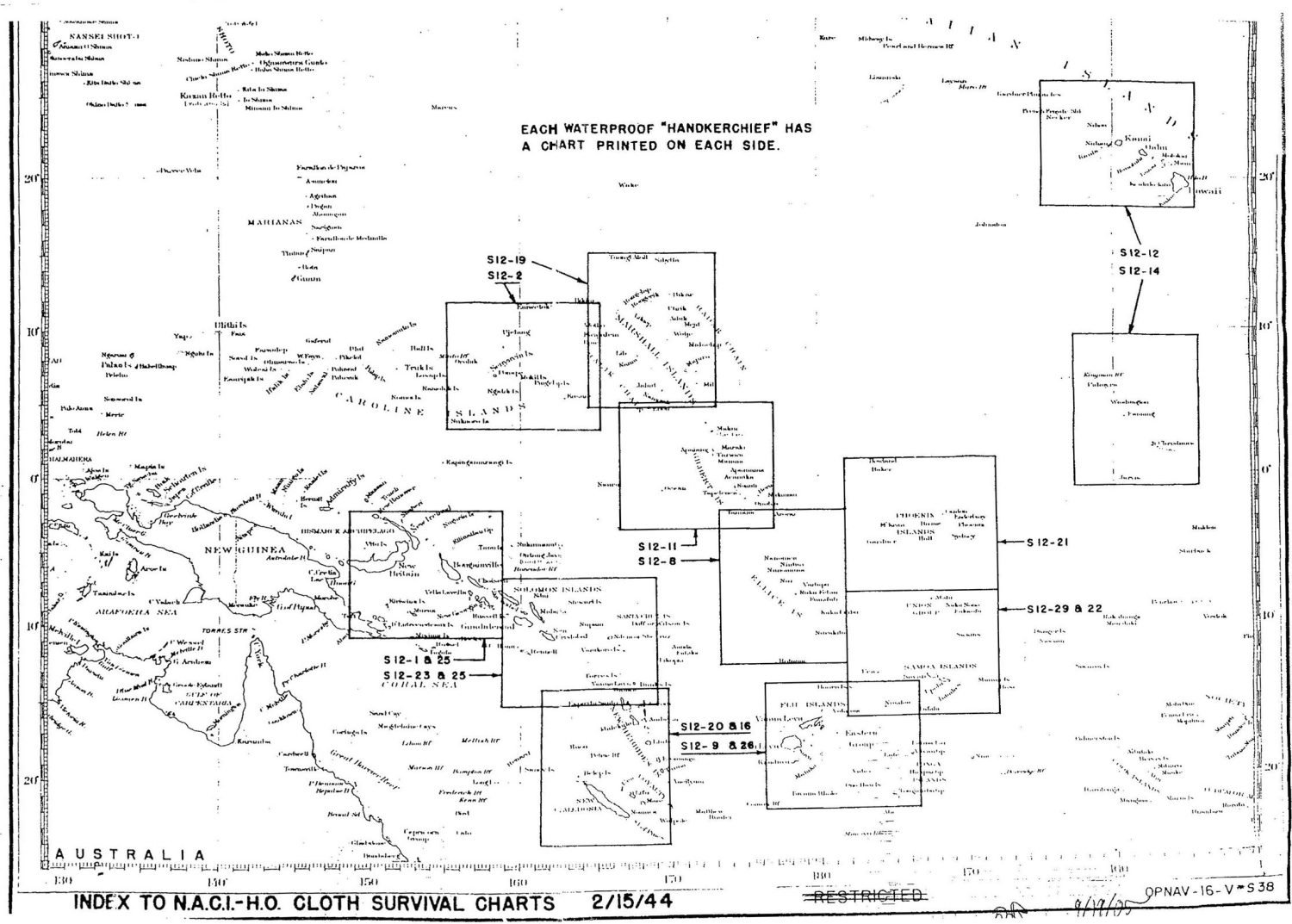

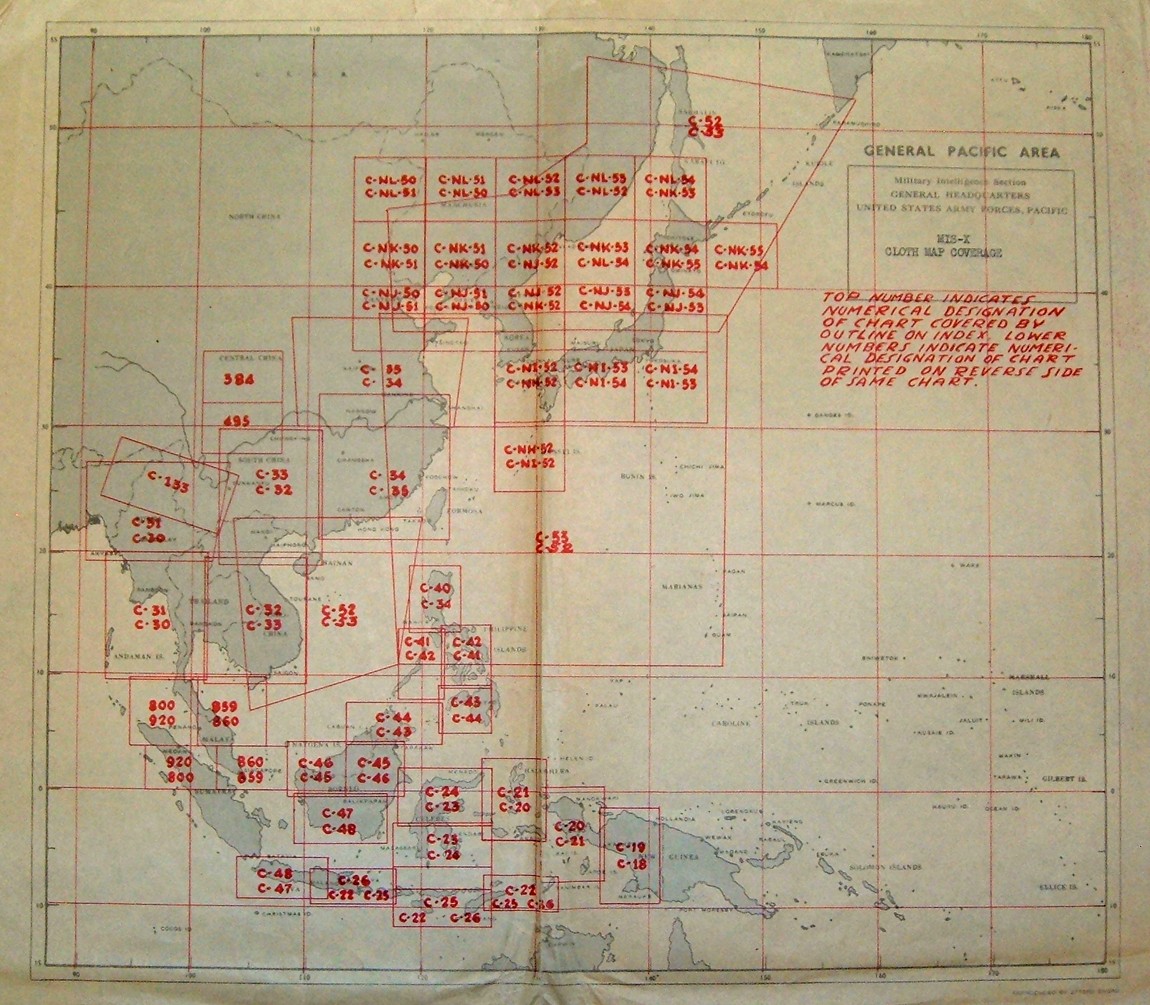

As mentioned above, both the USN and AAF recognized the utility of escape maps for its servicemen, and both organizations submitted requests for numerous publications. The U.S. Naval Air Combat Intelligence Office would ultimately issue 14 separate sheets, while the U.S. Army Air Force would distribute 38 different maps. Painstaking efforts were made to minimize deduplication of efforts, and the resulting division of the Pacific Theater can be seen in the respective index maps of each branch.

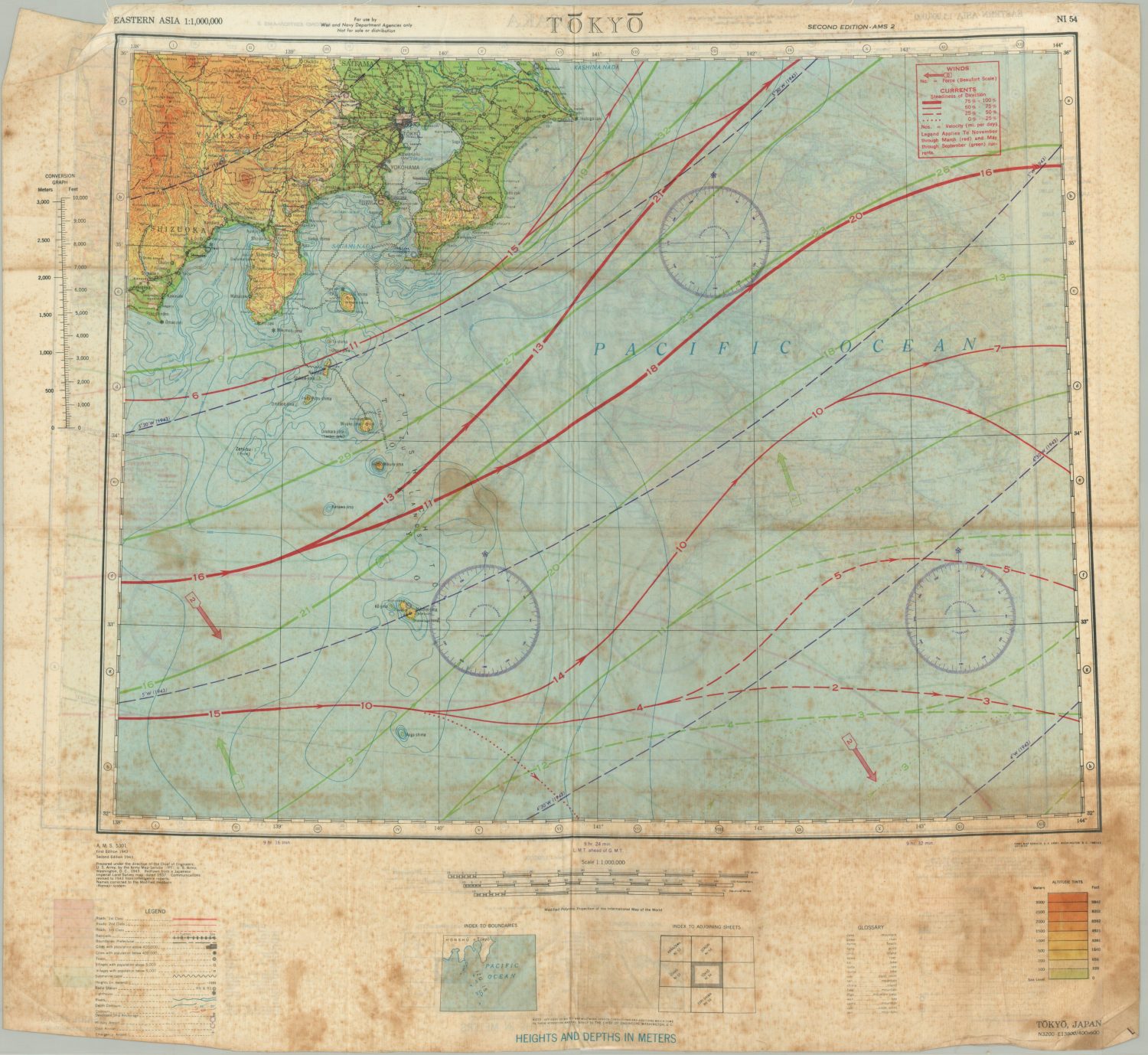

The information presented in maps created by both the USN and AAF is similar, but not identical. USN maps were intended for use by pilots operating from aircraft carrier or island-based airfields. They include detailed information on ocean currents and are known as “drift charts” for their utility as navigation aids for downed pilots.

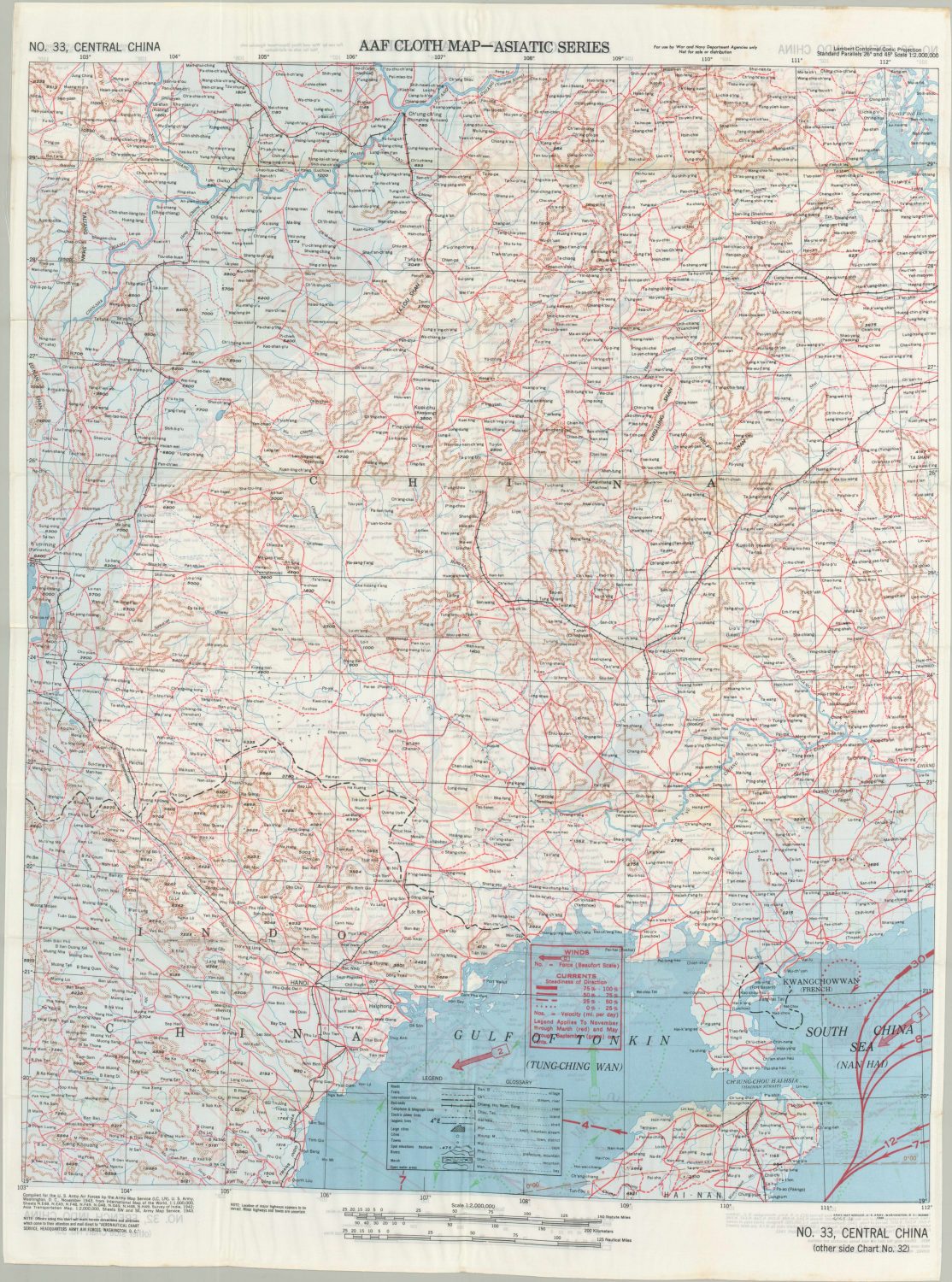

Maps used by the AAF were designed primarily for evasion tools to use by pilots downed over enemy territory. In turn, they include more interior details such as shaded topography, navigable rivers, and identifiable landmarks. Differences also occurred in seasonal variants, which showed updated wind/current information based on the time of year.

Despite deviations in utility, the goal was to maximize the efficacy of these evasion maps for all Allied troops in life or death circumstances. As such, a myriad of additional useful information is also presented on most silk maps. This includes small inset indices showing the relation of the sheet to others in the series, a glossary of useful terms, an extensive legend showing local infrastructure and geography, production history, and a scale (1:500,000 or larger).

The ability to quickly produced and distribute these silk maps on such a wide scale undoubtedly had positive effects for Allied forces. Of the estimated 35,000 troops who escaped Axis POW camps during the war, it is theorized that as many as half had access to an evasion map at some point during their journey. In addition to allowing a soldier to fight another day, successful evasion increased overall morale, sapped enemy troop strength, and boosted local partisan efforts. Over 3.5 million silk maps were distributed during the war – a number emblematic of the overwhelming material superiority enjoyed by the Allied cause.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief history of silk escape maps produced during World War II. I’ll be listing several examples for sale on my website over the next few weeks. Keep an eye out for future WWII e-mails, and feel free to drop me a line if you have any questions!

References

Astley, Joan. “British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations Vol. I and MI 9: Escape and Evasion 1939–1945.” International Affairs, vol. 56, no. 1, 1980, pp. 153–154., doi:10.2307/2615764.

Barber, Peter. The Map Book. Levenger Press, 2005.

Bond, Barbara. “Maps Printed on Silk,” The Map Collector, No. 22, Mar 1983, p. 13.

Giaimo, Cara. “How Millions Of Secret Silk Maps Helped POWs Escape Their Captors in WWII.” Atlas Obscura, Atlas Obscura, 22 Dec. 2016, www.atlasobscura.com/articles/how-millions-of-secret-silk-maps-helped-pows-escape-their-captors-in-wwii.

“WWII Silk Maps and Cloth Maps Escape Maps.” WWII Silk Maps and Cloth Maps Escape Maps, www.escape-maps.com/.