“To the Chicago Daily News:

Any undertaking destined to increase the brotherhood in arms existing between Americans and Frenchmen merits encouragement. Since your book aims to give an idea of the French war organization, I can only congratulate you on thus presenting to your compatriots documentary evidence of facts which are of the greatest interest…by adding their skill in battle to their well proven courage, Frenchmen and Americans will reap new glory and will once more carry to a triumphant conclusion the idealistic principles for which they have at all times freely shed their blood.” – Marshal Joffre, Introduction.

This little ‘war book’, just less than 200 pages, was published by the Chicago Daily News Company in 1918 for distribution, free of charge, to American servicemen (in uniform) who called upon the firm’s main office in Chicago. Subsidized copies were available at overseas branches in London and Paris, while the general public could buy one for twenty-five cents (about $6 today). The Daily News was rightfully proud of its foreign news service, since in the 1890s, it was one of the first American dailies to open a full-time international correspondent’s office. Such contacts and experience were crucial in setting the newspaper apart from rivals like the Chicago Tribune, which would claim the city’s highest daily readership the same year the book was issued.

America’s entry into the Great War in 1917 brought mixed public opinions. Strong isolationist feelings and large populations of pacifists, progressives, and German emigrants tempered enthusiasm for conflict against increasing geopolitical and economic pressures. As a result, the Committee on Public Information was organized by the Wilson administration to influence popular belief in support of the war. This propaganda mandate, led by chairman George Creel, extended into the visual arts, film, and printed communication (especially newspapers). While the Chicago Daily News War Book does not appear to have any direct affiliation with the CPI, it almost certainly received financial support, useful information, or, at a minimum, tacit approval for issue.

These priorities are reflected in the content and organization of the pocket-sized reference volume, which would have been tucked into the kits of thousands of young men as they made ready for war. There is a clear contrast between the information “designed to aid them in the discharge of their duties” (according to the editor, Josephus Daniels), pro-war advocacy, and what might best be described as a travel guide to Paris. Explanatory diagrams for armaments and ordnance are included alongside lists of cafes, restaurants, and theaters. Words for dozens of popular French dishes are given in the accompanying French/English dictionary, with military terminology given a clear backseat. Secretary of War Newton Baker alludes to this ‘multi-purpose’ style in his introductory remark, “I am sure that the little book will be of real value, not only to the men for whom it is directly prepared, but to many others.”

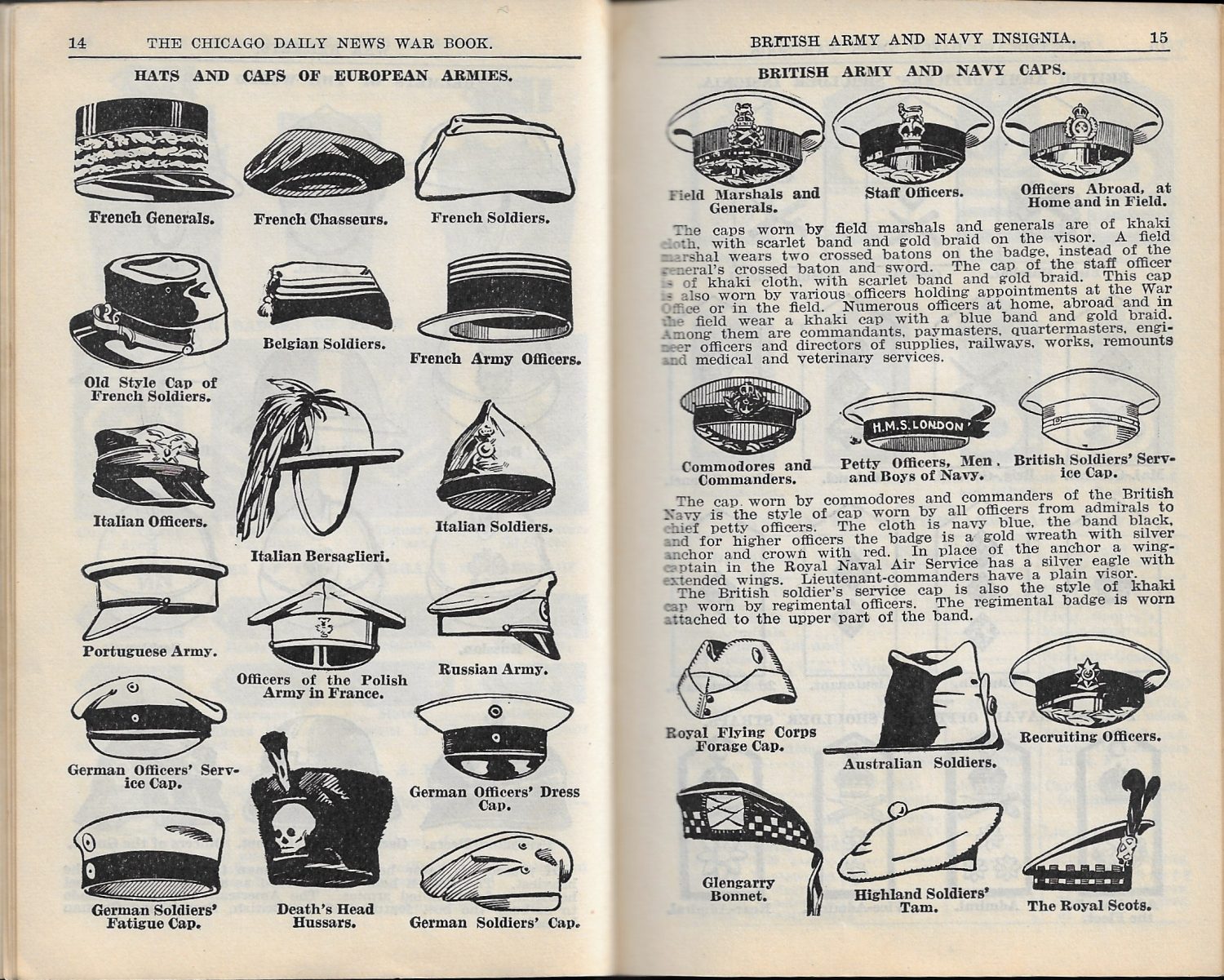

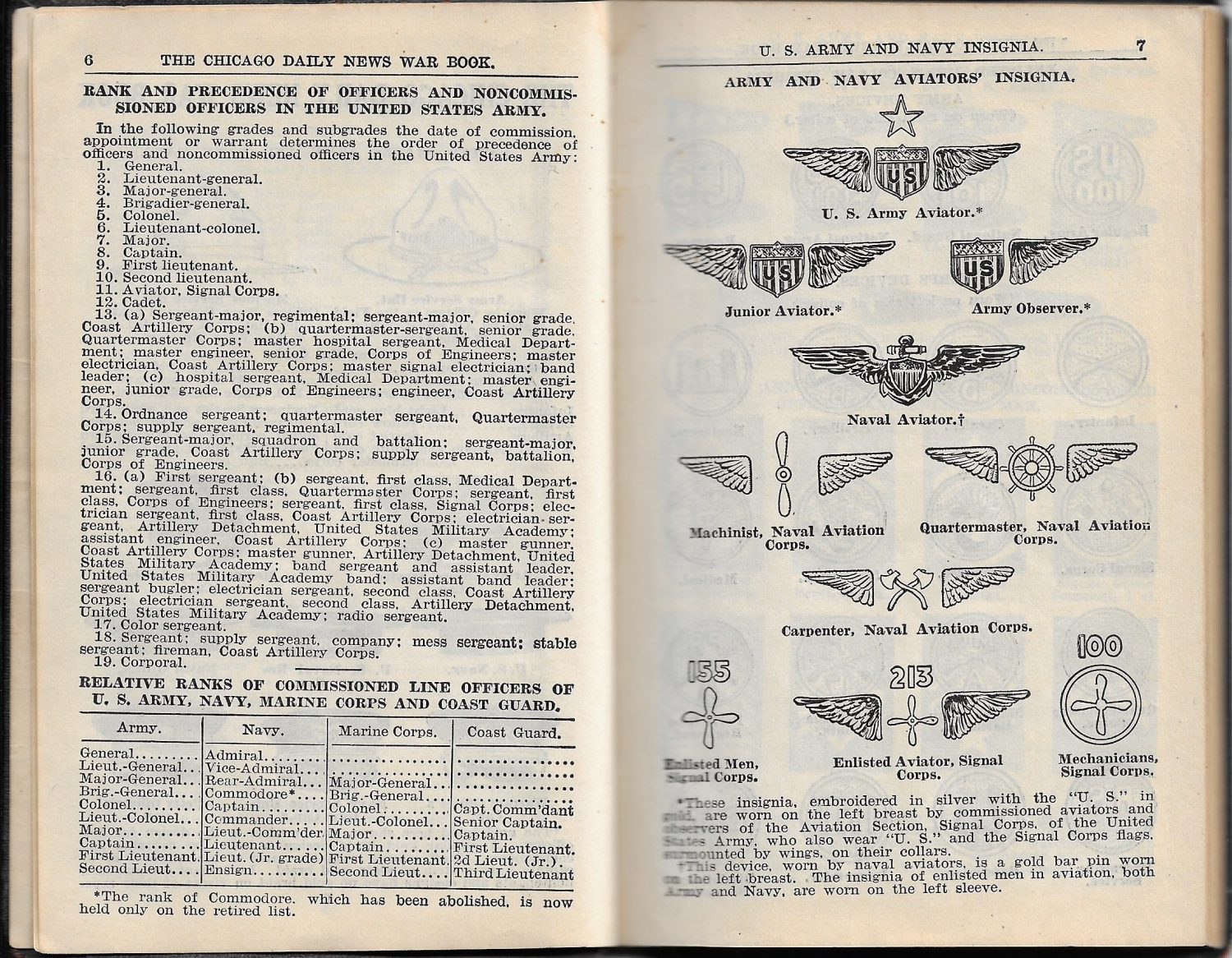

The stage is set through the presentation of uniforms and insignia – rank is a foundational element to nearly all branches of the Armed Forces around the world and knowing the adornment of fellow soldiers and officers is crucial to discipline and morale. Images of hats, buttons, shoulder insignia, braids, shoulder bars, and helmets reflect a huge variety of form and function, as well as the distinctive identities enjoyed by combatants on both sides. World War I expedited the standardization of uniforms and saw the end of the more colorful or flamboyant martial displays, previously typified by Messimy’s claim, “Le pantalon rouge, c’est la France!” [The red trousers are France!].

Continuing the theme of military glory, war decorations and awards come next. Illustrations and descriptions of the Medal of Honor, Victoria Cross, Medaille Militaire, etc., are provided, along with examples of the outstanding valor that earn such impressive commendations. These are treated somewhat like comic book heroes – introduced with a catchy title or nickname before a summary of their wartime exploits. Stories like little Drummer Walter Ritchie, age 15, rushing a German trench, beating to sound the assault, undoubtedly set (unreasonable) expectations of bravery among the men. Furthermore, only select information is presented. One notable example is the excerpt for French ace Georges Guynemer, which omits to mention that he went missing in action in September 1917!

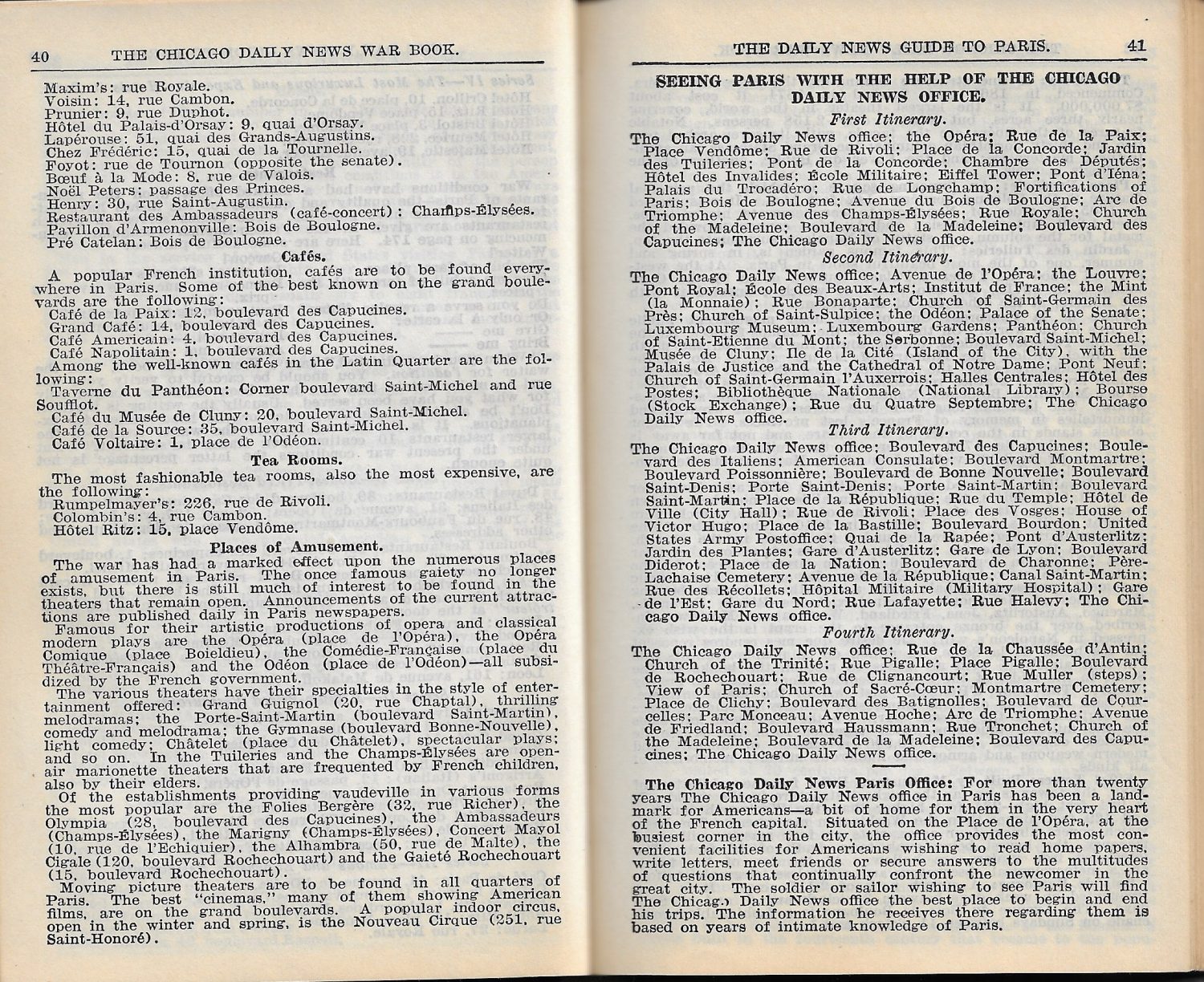

The Foreign Legion Cross of the Legion of Honor is followed somewhat abruptly by The Chicago Daily News Guide to Paris. Even in the darkness of war, the City of Lights would have been awe-inspiring to all but a few. Visitors were encouraged to make use of the reading and writing rooms at the branch office. A wealth of general travel details is provided, including tips on transportation, important addresses (including banks from which the well-off could draw funds), best practices (gratuity, dining out, etc.), expected costs, and accommodations. Summaries of major attractions are provided, along with recommended itineraries for trips around Paris. Sadly, the Louvre was closed to the general public. The streetcar and bus system is described as unsatisfactory (for obvious reasons), but the network of Metro lines makes much of the city quite accessible to the average soldier.

“War conditions have had a marked effect upon the restaurants of Paris – the quality and quantity of the dishes have suffered, the prices have gone up.” – pg. 39. Popular hotels and restaurants are ranked according to cost and luxury level. An enlisted soldier could stay at the Y.M.C.A. for as little as 3 francs/night, though prices for the exclusive Hotel Ritz, Hotel Crillon, etc. are unlisted. A bit of practical advice encourages the patron to avoid getting fleeced by carefully reviewing a bill and that a tip of more than 10% is also expected in most circumstances. Last, but not least, numerous places of amusement, including vaudeville shows, cabarets, and operas, harken back to the days of the Belle Époque. ‘The once famous gaiety no longer exists, but there is still much of interest in the theaters that remain open.” – pg. 40. Of notable interest is the legendary Folies Bergere, which began management under Paul Derval the same year as publication (1918).

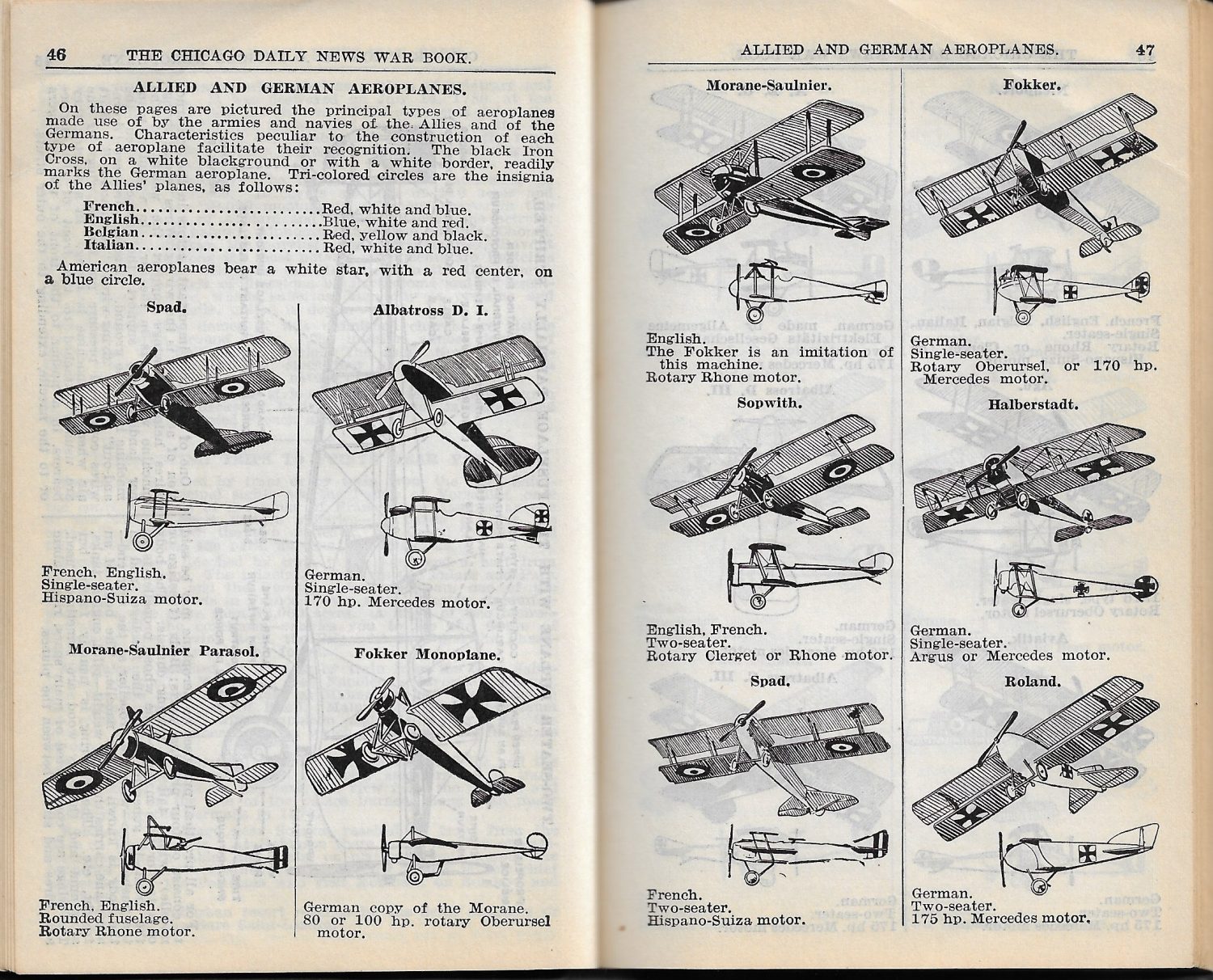

Almost as suddenly as it started, the Guide to Paris ends. Attention once more turns to military matters and a section on aviation begins with a cross-section of a two-seater biplane, still a novel machine to most men in uniform. Features to help identify each combatant’s fighters are not only interesting but potentially lifesaving. It was provided for training and familiarization with the hopes of minimizing friendly fire. A fascinating variety of aircraft designs are showcased, including several ‘pusher’ style planes with the propeller behind the pilot. “The details of organization of the American army aviation squadron cannot be published.” – pg. 50.

The Codes and Signals section offers some of the most practical advice throughout the entire volume (though men assigned to the Signal Corps would already be expected to know this information front and back). The inclusion of several varieties – International and American Morse Code, semaphore signals, ardois (light) patterns, and a list of wireless stations – all highlight the relative unreliability of wartime communications.

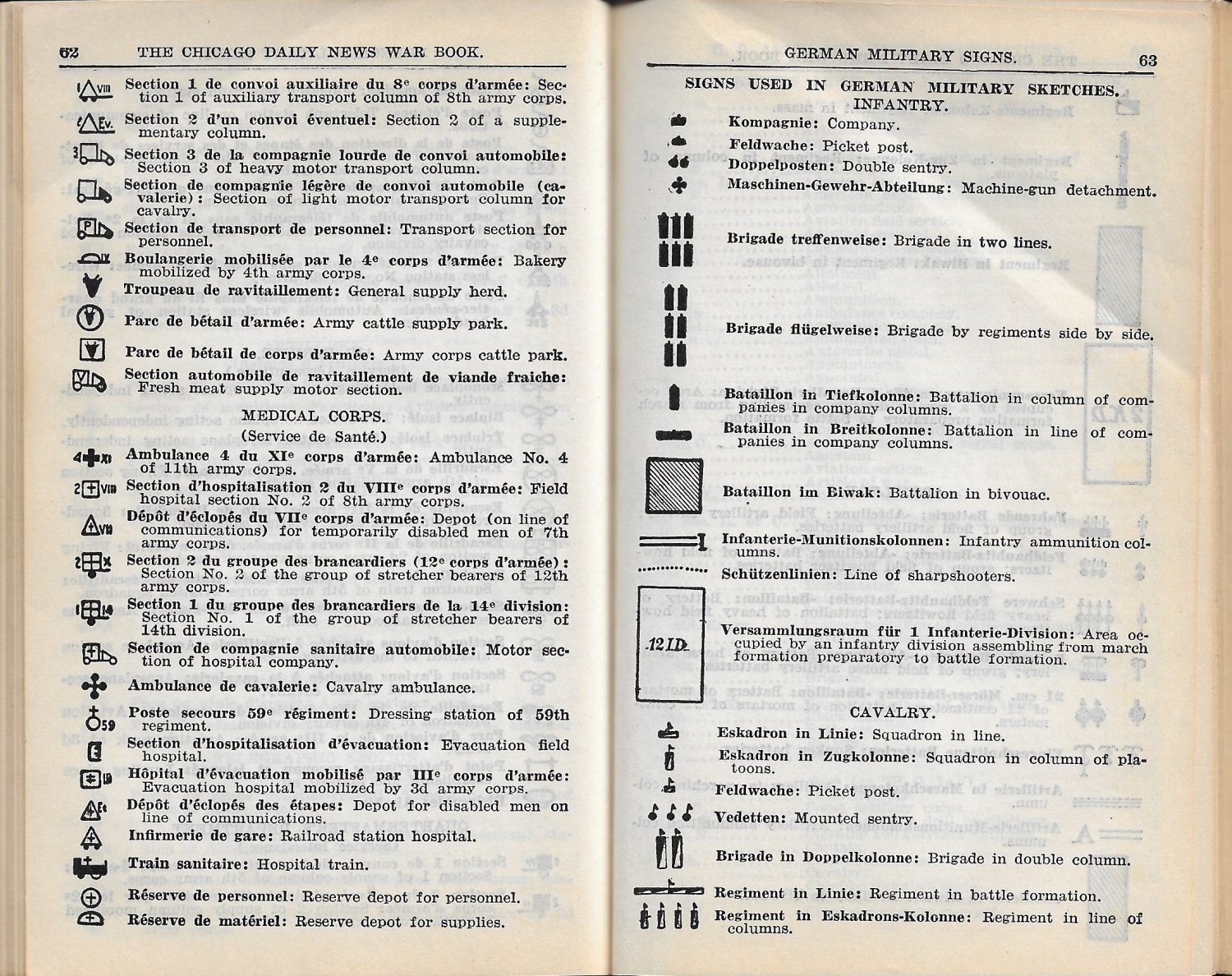

Military signs, symbols, and abbreviations for American, French, and German armies offer valuable insight into the (often confusing) composition of the different forces. Notably, the U.S. utterly lacks any diversification of armored units, while French names for ‘Infantry in Line’ and ‘Infantry in Column’ give whiffs of the Napoleonic era. Also of interest is the heterogeneity of the automobiles in use (over a dozen different types). This reflects the organizational complexity of modern warfare, though with few of its conveniences – mobile workshops, ambulances, veterinary stations (for the horses), field kitchens, ration transport, ammunition storage, and more were required. One can only imagine the flies swarming around the meat wagons (voiture a viande)!

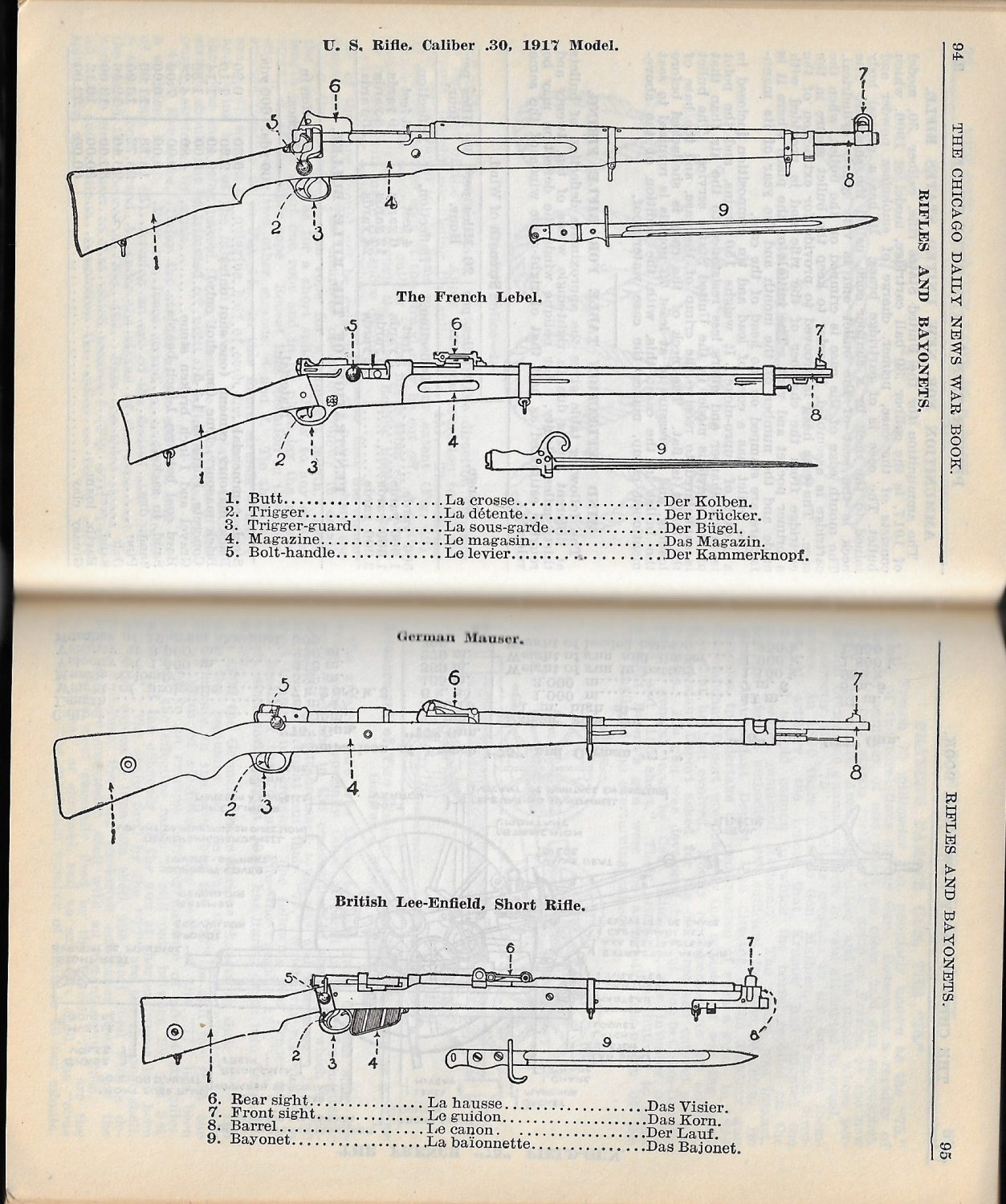

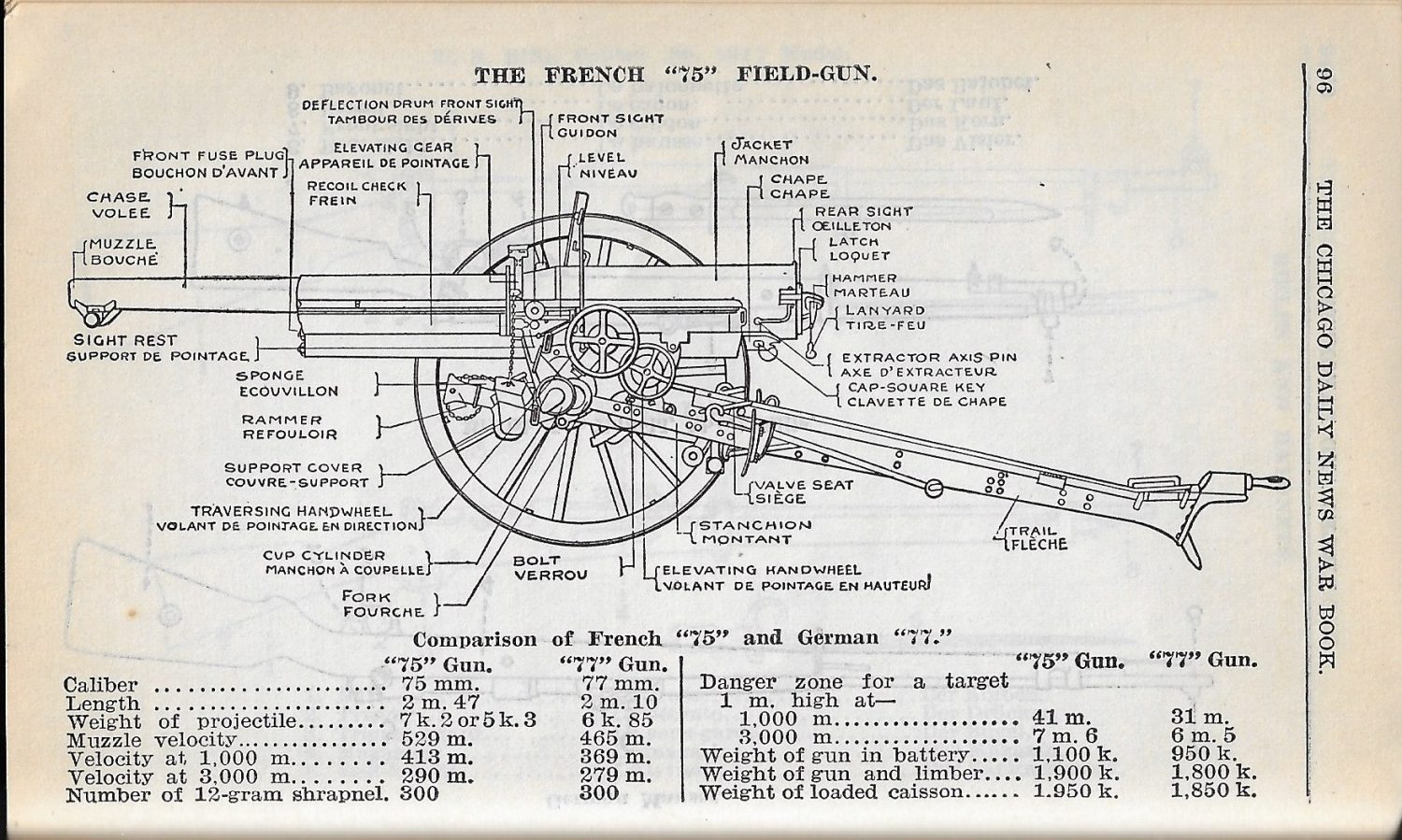

Diagrams and instructions for dozens of knots, lashes, and cord splices are eminently useful, along with information about the basic functionality of the M1917 Enfield. Technical drawings of this rifle, plus the French Lebel, German Mauser, and British Lee-Enfield, are provided. Subsequent illustrations detail the use of the famous French ’75’ Field Gun (and its limber) and the stifling ‘forty-and-eight’ railcars, named after their designed purpose of transporting forty soldiers or eight horses. “Under no circumstances are the boards to be removed from the cars.” – pg. 98 (they got to be quite stinky). French road signs are also listed.

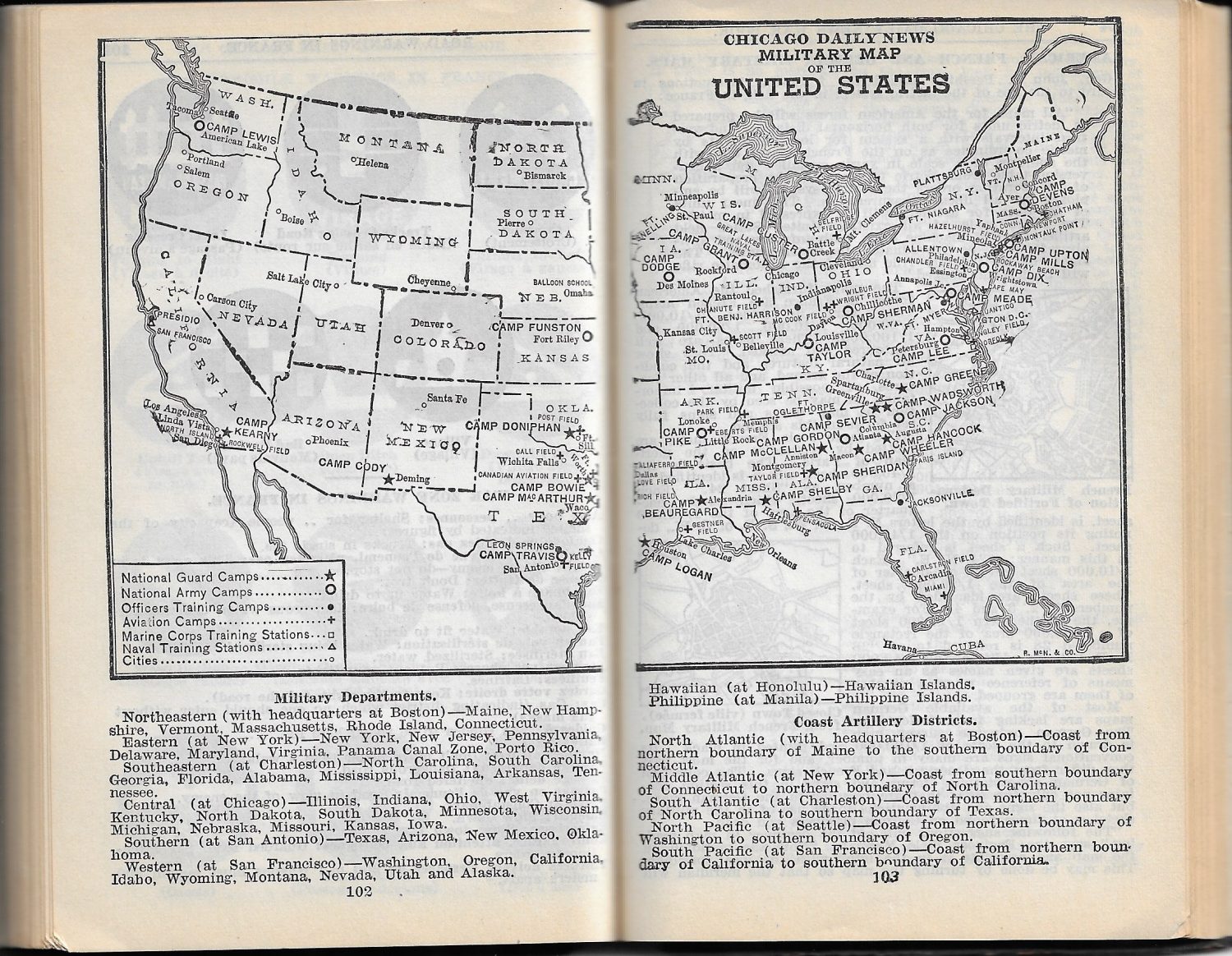

The volume wouldn’t be blog-worthy if it weren’t rich in map-related features. Apart from the previous city plan of Paris, there is a Military Map of the United States that locates facilities from coast to coast for each branch of the armed forces. The image, created by the Chicago-based mapmaking firm of Rand McNally, includes Coastal Artillery Districts, which is somewhat surprising. Given that the guide was designed for use near the combat zone, one would think this information might be considered confidential, but it doesn’t seem like the Germans could do much with it, anyway.

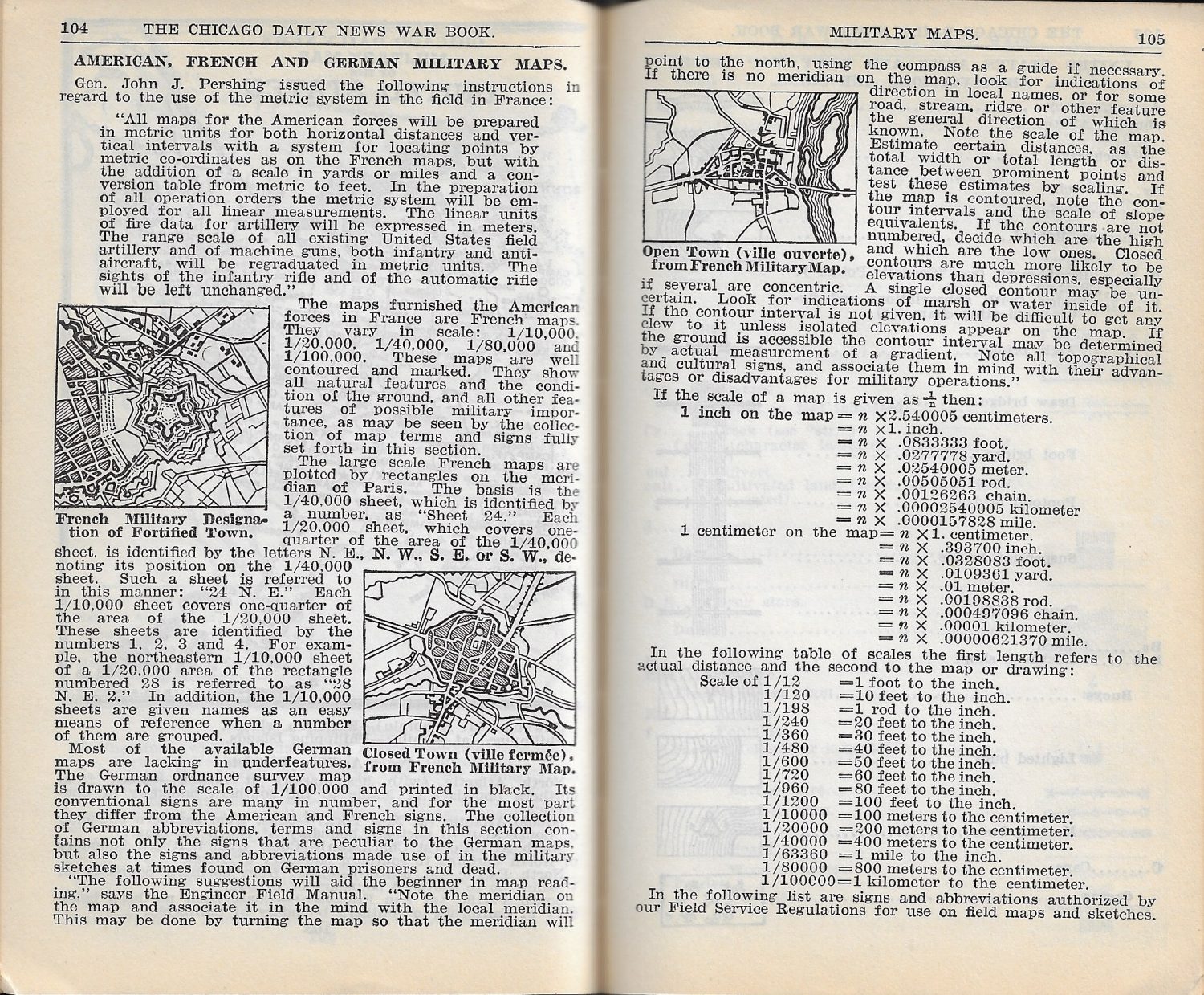

This is followed by an extensive selection on American, French, and German military maps that outlines specific features and symbols used on each. Here, the martial priorities of the Germans are shown, as they generally have more pragmatic elements than the various religious and civic facilities shown on French maps. Of particular interest are the baum (a conspicuous tree), numerous types of bridges, cemeteries (divided into Christian and Jewish), and fields of hops.

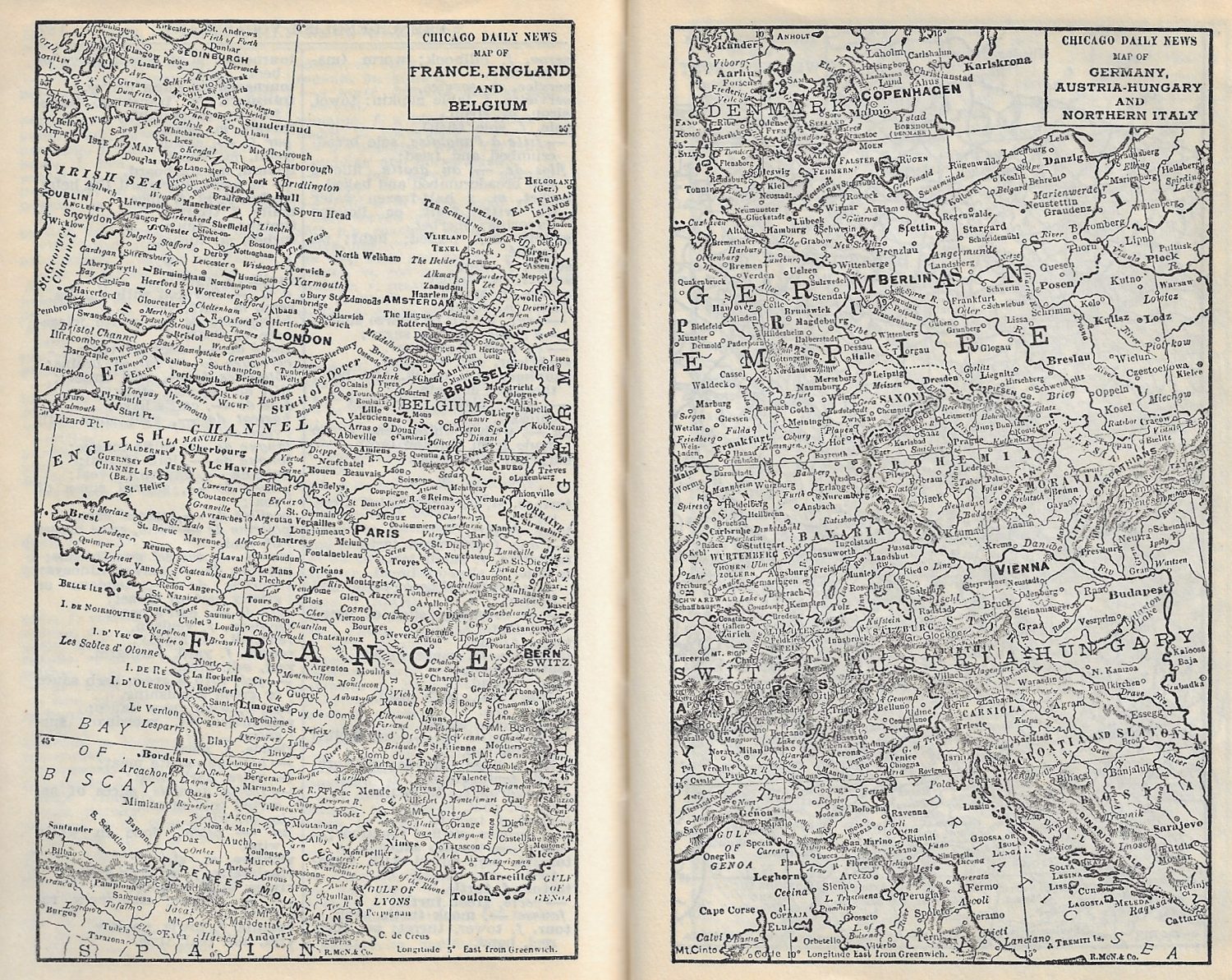

Rand McNally & Co. provides three further maps covering areas of conflict in Europe, as well as the line across the Western Front. The first conveniently partitions the continent into an ‘us versus them’ format; with France, England, and Belgium (and their American supporters) in the left corner, facing off against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and a rather unreliable (albeit Allied) Italy on the right. The small scale limits the practical directional use – though the many place names would have been convenient references for news dispatches, new personnel introductions, or rumors of impending orders.

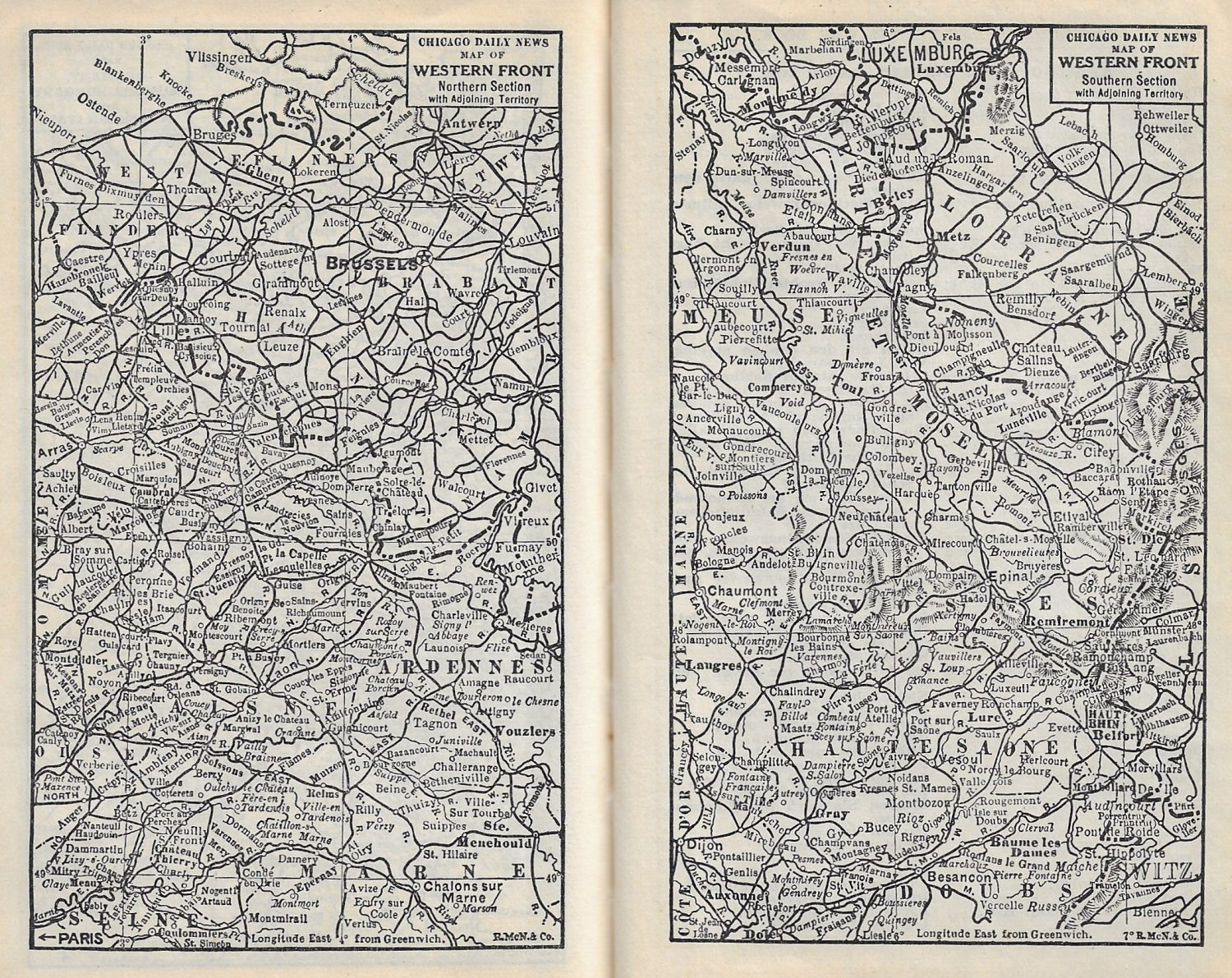

The Map of the Western Front is divided into northern and southern sections, though no attempt whatsoever is made to locate the position of the front. Thick, dotted lines represent prewar borders, while the continental railway network connects the major towns and depots with apparently unbroken lines. Though the Russian Revolution of 1917 limited fighting on the Eastern Front, much of the Russian Army remained intact through the peace negotiations, pinning down thousands of German troops and continuing to (indirectly) aid the Allies. It’s quite surprising that no reference is made to that geographic sphere of the conflict – possibly in fear of ongoing Bolshevik success and feelings of betrayal from the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1918 (ending Russian participation in the war)?

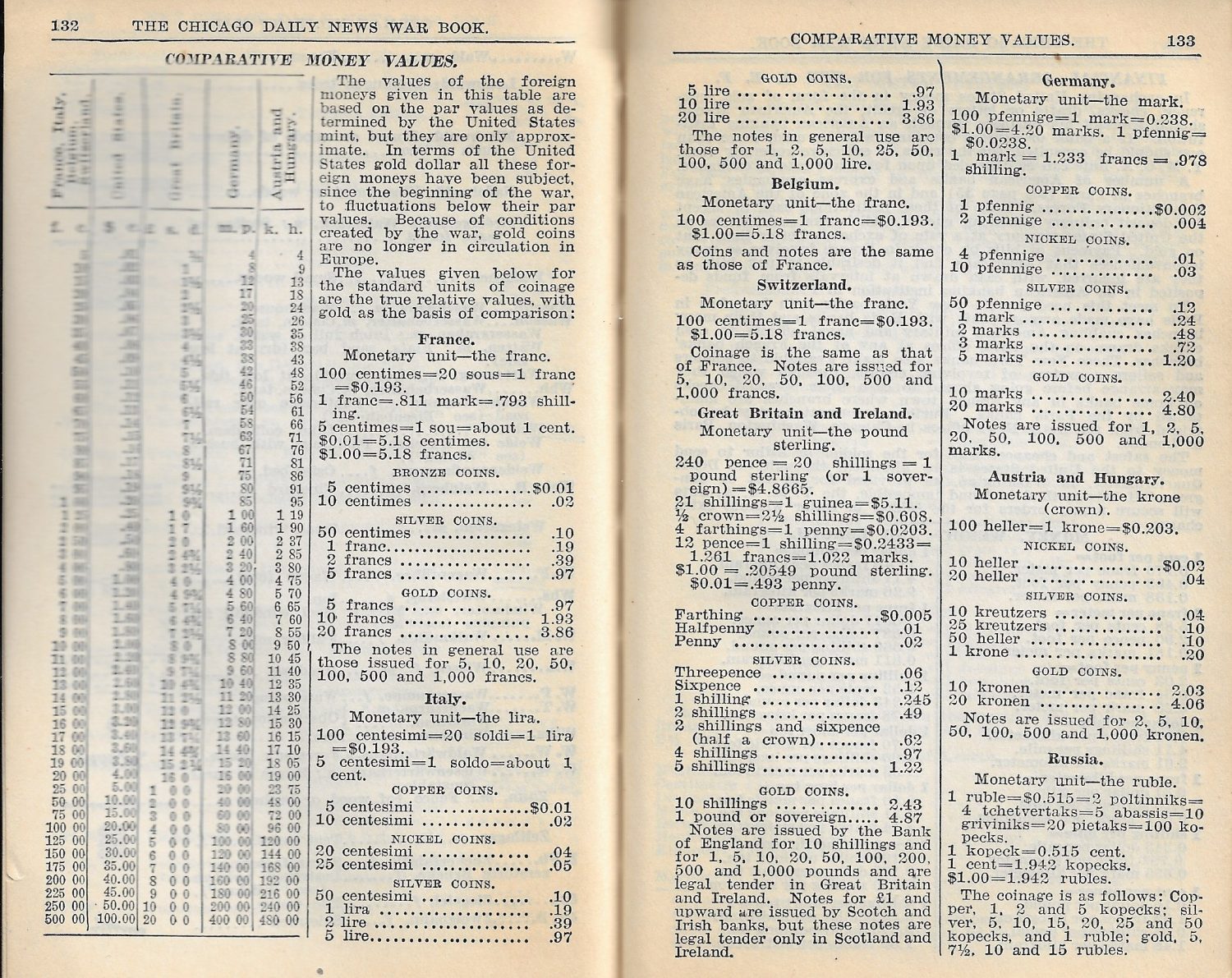

“Because of conditions created by the war, gold coins are no longer in circulation in Europe.” – pg. 132. Currency conversions (apart from the language barrier) were likely one of the more unfamiliar aspects of a young American soldier on leave. This table is of tremendous help when calculating dollars and francs to marks or shillings, but it fails to account for the rampant inflation that often plagued wartime markets. Here is one of the few references to Russian participation in the conflict (then in the midst of the Civil War), with one ruble equivalent to about 51 cents, 2 poltinniks, 4 tchetvertaks, 5 abassis, 5 griviniks, 20 pietaks, or 100 kopecks. Additional tables and conversion equations are given for changing standard units of measurement to metric (also undoubtedly a huge complication), and vice versa.

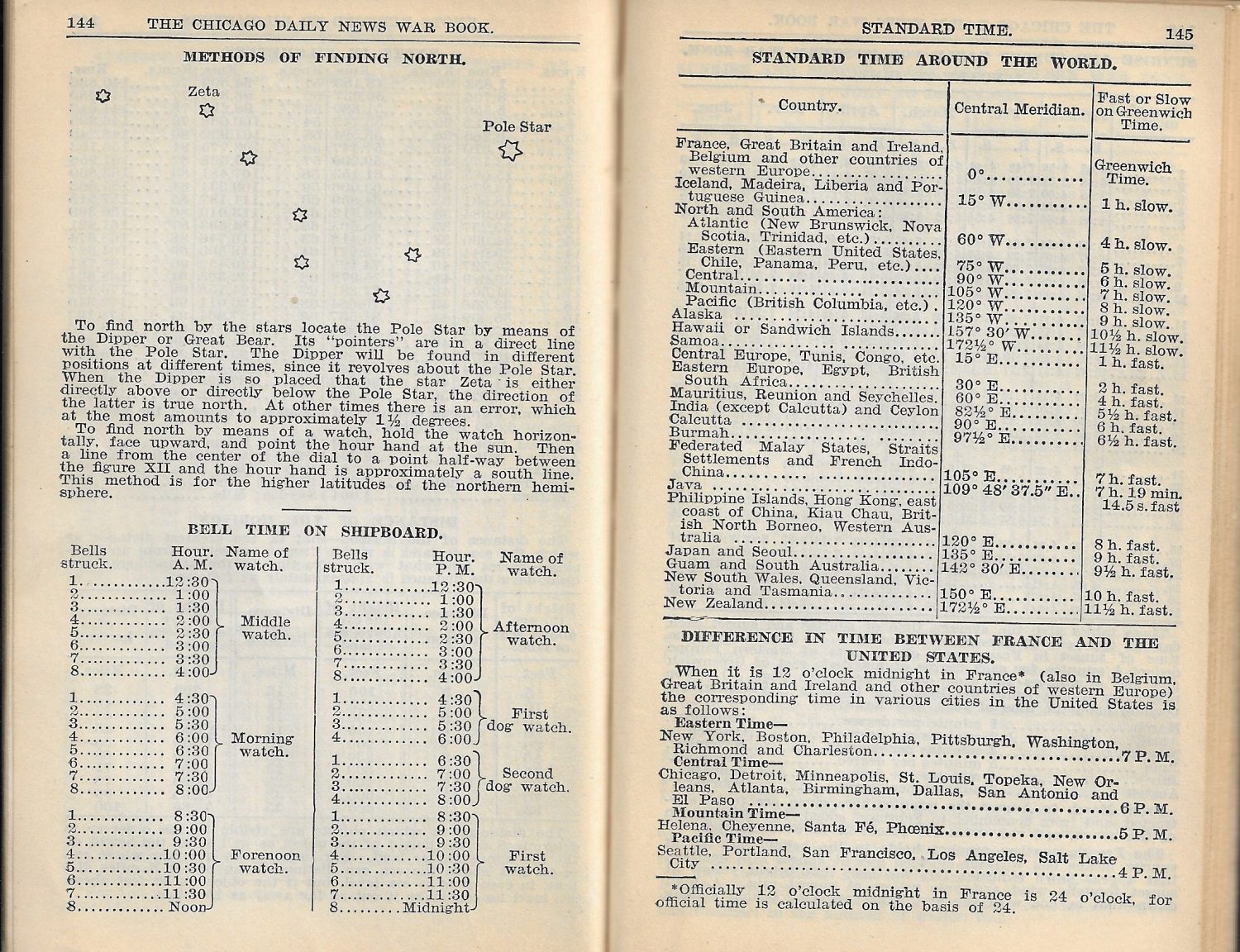

Time changes and shipboard routines would have also been strange aspects of overseas deployment for the fresh American doughboy. Bell time, points of the compass, and relative bearings at sea were helpful to know while aboard ship, but any sailor worth his salt would have these drilled in through months of training.

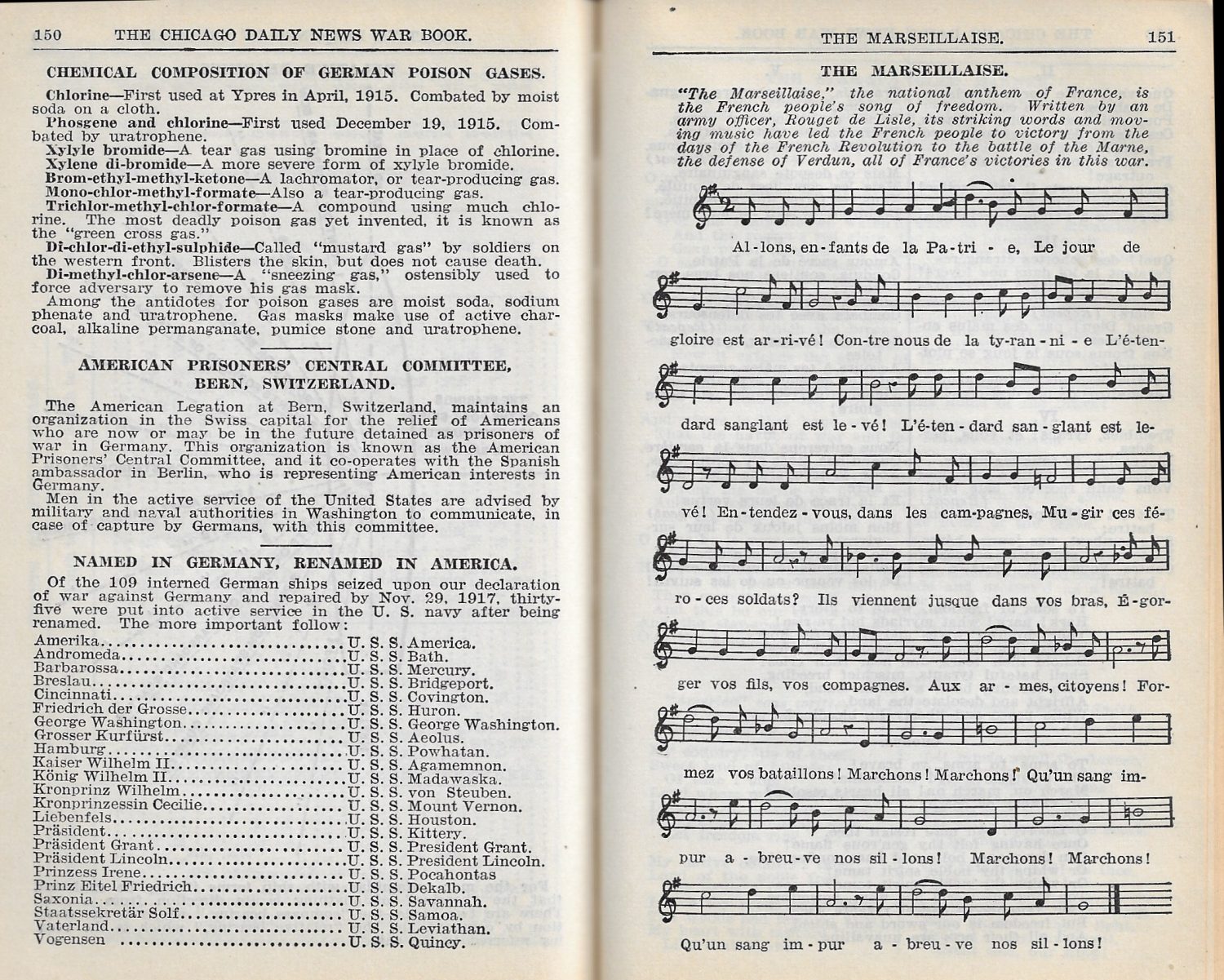

Tucked between these maritime references and patriotic songs like The Marseillaise and the Star-Spangled Banner are somber entries that list the chemical composition of German poison gases, contact details for American prisoners of war, and a list of prominent interned ships (renamed for use by the U.S. Navy). While brief, the first two represent the rare mention of authentic wartime hazards to the audience. “Men in the active service of the United States are advised by military and naval authorities in Washington to communicate, in case of capture by Germans, with this committee.” – pg. 150. About 4,100 U.S.soldiers were taken prisoner during WWI. The American Prisoners’ Central Committee was one of several organizations given authority by the government to support captured Americans. The date given for the renamed ships also offers an idea of the timeline of production for the book (early 1918, using data collected in November 1917).

The fact that the French National Anthem comes before that of the United States is a striking one. Perhaps the publishers wanted the doughboys to impress the crowds of French onlookers upon debarking? Other American war songs include the Battle-Hymn of the Republic, Dixie, and the Marines Hymn.

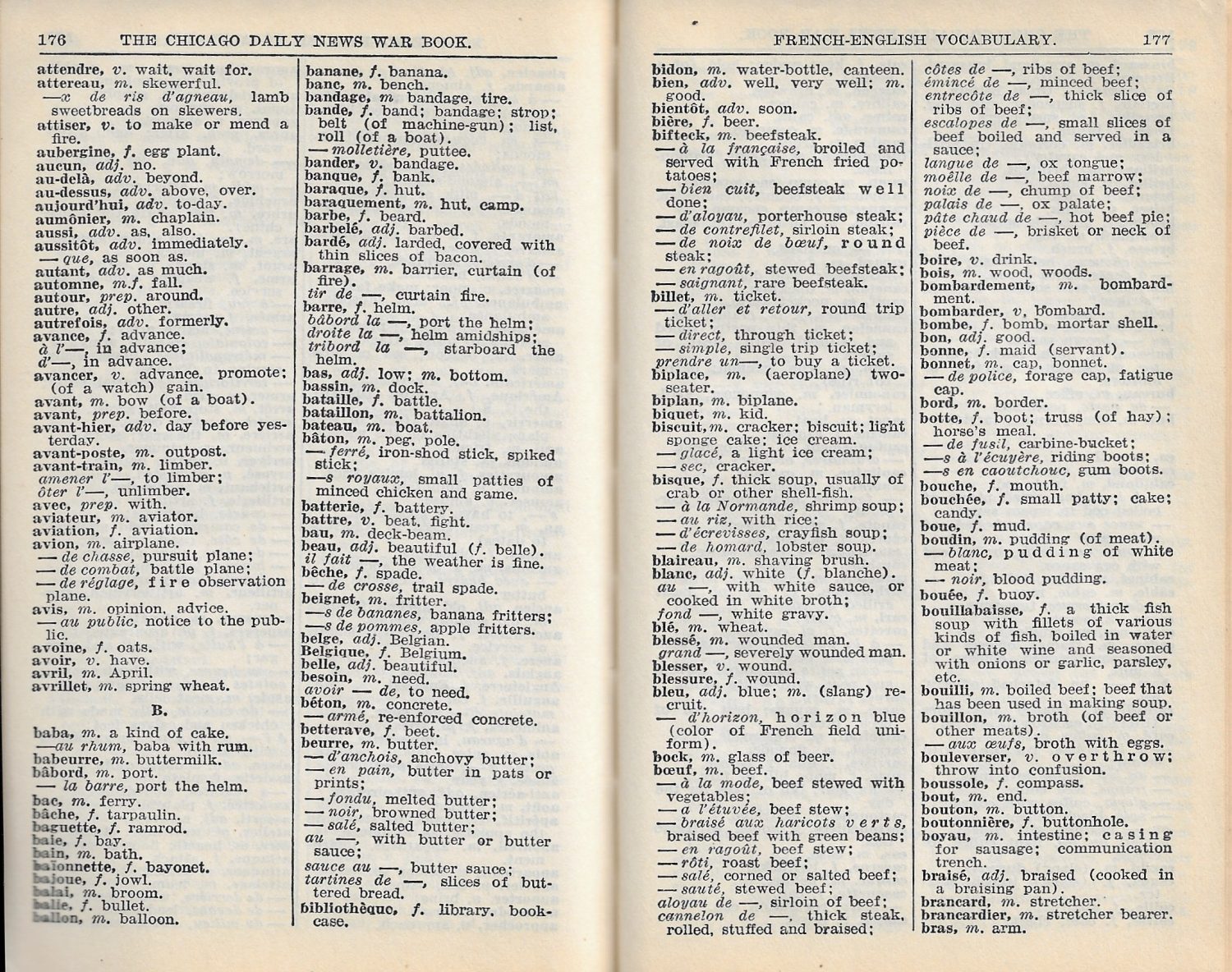

The French-English dictionary covers a whopping 32 pages and offers perhaps the most revealing insight into the intended use of the book – the gastronomic conquest of Parisian restaurants, cafes, and patisseries. Couvert references a tablecloth, rather than cover from artillery fire. Faux is accompanied only by filet (to indicate the tenderloin has been removed from the steak). Specific words are given for over a dozen different preparations for eggs (excluding omelettes), nearly twenty soups, sixteen lamb dishes, and a whopping thirty-four different orders for beef (including faux filet)! Specialties include croquettes de volaille, pate froid de gibier, coquille de homard, merlan a l’anglaise, and perigord truffles – hardly the repast to be expected from a nation enduring over two years of war. The variety in cuisine contrasts sharply with the military terminology – less than eight words are given (each) for the broad categories of munitions, fuel, and armaments (ground and air).

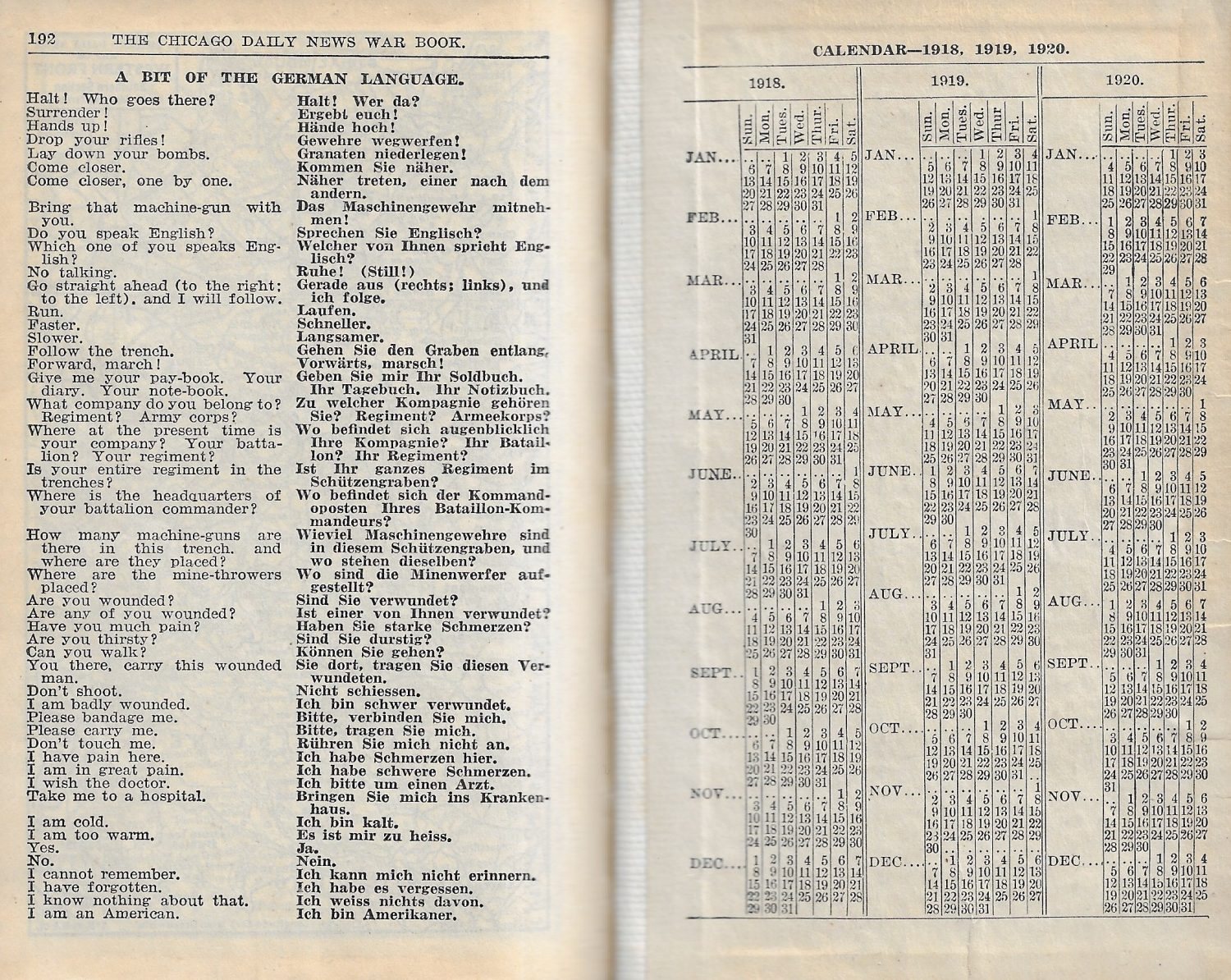

The Chicago Daily News War book concludes with a ‘Bit of the German Language.’ Contrasting sharply with the French dictionary, this one-page reference is strictly military. Instructions for surrender and detainment, inquiries about the enemy positions, and three different versions of ‘I don’t know’ (excellent for use when captured) comprise the majority of the fifty or so entries. Specific attention is given to machine guns and the minenwerfer (mortar) – two particularly effective instruments of war that the Americans had likely heard a great deal about from the French. Commands for ‘Run’, ‘Give Me Your Pay-Book’, and ‘You There, Carry this Wounded Man’ allude to the darker realities of combat.

A daily calendar for 1918 – 1920 serves as the back endpaper. Fortunately for those carrying the book (and those without), the conflict officially ended on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, in 1918 – meaning that very few of these war books ever made it to the battlefield! After a one-sided peace process concluded with the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, the Roaring 20s (or the années folles in France) would help the survivors (on the winning side) forget the horrors and lessons of war.

The final words in the Chicago Daily News War Book, as shown above, are the German translation for ‘I am an American.’ I think this captures the volume’s rather self-centered perspective quite well. There is no dramatic call to arms, historic exposé on the causes of the war, or broad attempt to justify intervention for global peace. The lack of recognition for the Russian contribution seems unconscionable, even given political tensions during the ongoing Civil War. The Belgians have been equally overlooked. Further, it’s extremely callous to only acknowledge the suffering of the French through the negative impact on hospitality and cuisine, especially for a news service that claims such pride in its foreign service.

Another startling example of Americentrism commemorating World War I, totally omitting the first two years of the conflict.

The war book seems closer to an officer cosplay guide to war while in Paris, with particular emphasis on ‘have a good time’ and ‘don’t embarrass us.’ There is a distinct lack of practical information for the men in the trenches – how to communicate back home, lists of recommended items, tips for maintaining health on the front, even a recipe for ersatz coffee might have brought some comfort for the soldier who made space for the book in his knapsack. While a doughboy fighting on the Western Front might not have had the chance to order petite gateaux using the French-English dictionary, the convenient sizes of the pages would have certainly made for good toilet paper!

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to own your own copy of the Chicago Daily News, check out the product page here for availability. Let me know if you have any questions or if you have anything to add to the post.

Further Reading/Sources:

- Smithsonian Magazine – How Wilson’s Propaganda Machine Changed American Journalism.

- Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Chicagology

- U.S. State Department

- PBS – The Great War: American Experience

- National Endowment for the Humanities

- National Park Service – The United States and the First World War

- The U.S. Army in World War I