“The Million” was a term used in England during the Victorian era that represented the masses of laboring people – a group distinctly separate from the wealthy aristocracy. Contemporary advancements in printing technology and a new focus on public education saw huge growth in published literature aimed at this working class in the mid-19th century. Newspapers, periodicals, cookbooks, encyclopedias, and informative volumes like Joseph Mainzer’s Singing for the Million proliferated. One early publisher and a strong promoter of this movement was the aptly-named Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, or S.D.U.K.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, education reform began to gain traction across England. Parochial schools were launched in 1807 to help educate the children of the poor and infant schools followed in 1818. However, most non-formal schooling was supported exclusively by wealthy philanthropists or the church. A group of progressive reformers began to persuasively argue that public education was a prerequisite for political reform. One leading example was Henry Brougham, a journalist, lawyer, and statesman who was first elected to Parliament as a Whig in 1810. Brougham was a vocal advocate for the abolition of slavery, free trade, and greater power for Parliament (at the expense of the monarchy). He saw literacy as a means to combat poverty and encourage social stability. In 1820, he catapulted into the public spotlight after successfully defending Queen Caroline of Brunswick against her husband’s (King George IV) attempt to annul their marriage.

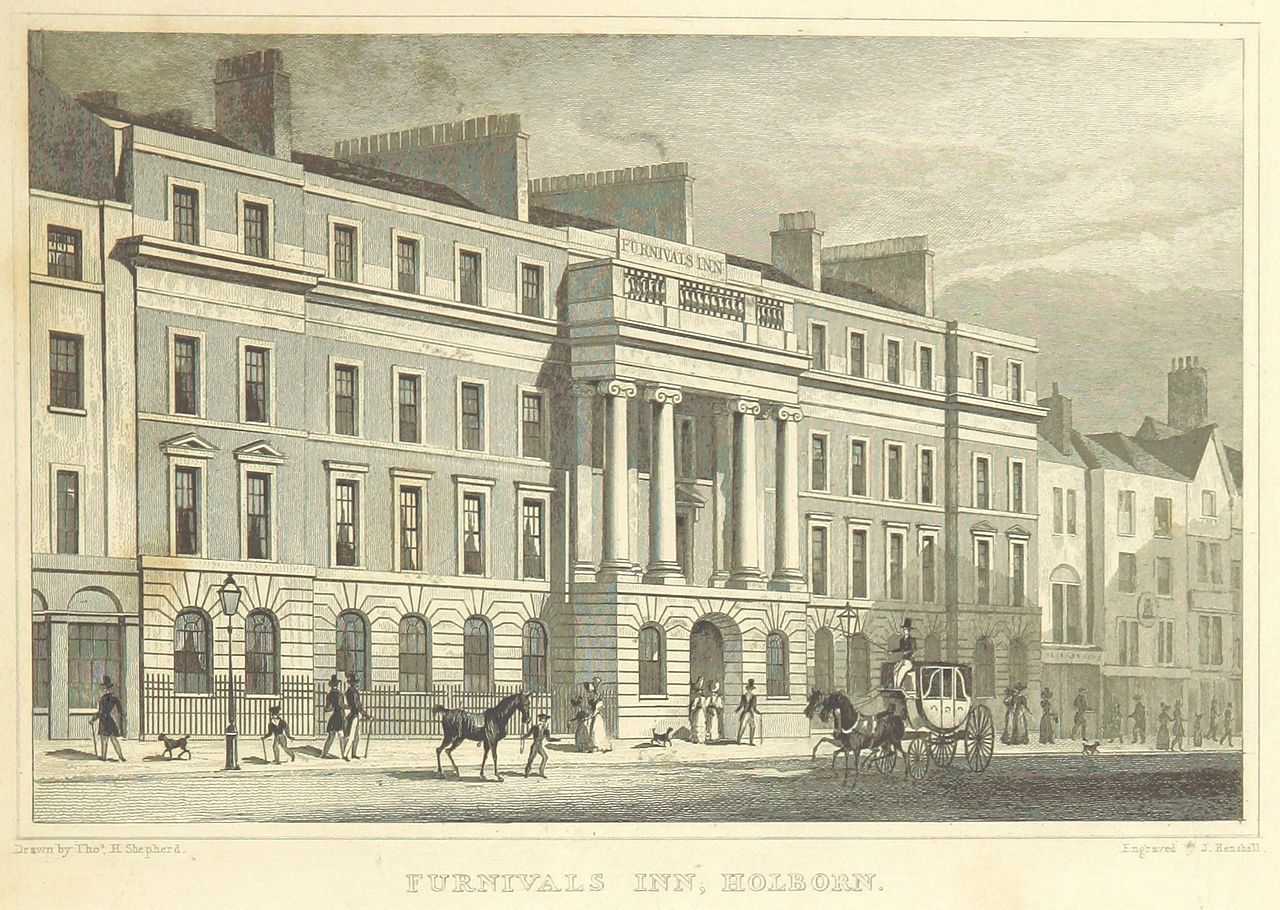

In November of 1826, Brougham led the first meeting of the General Committee of the S.D.U.K in London’s Furnival’s Inn. Minutes record a primary assumption “that the progress of improvement among the People is chiefly obstructed by the want of Elementary works upon the various branches of Knowledge, written in a plain manner…and published at a low price.” Taking their name literally, the organization began to print scientific magazines known as sixpenny treatises covering a variety of topics as part of its Library of Useful Knowledge. It would later expand into an encyclopedia, a Library of Entertaining Knowledge, the immensely popular Penny Magazine, and a detailed series of maps. Technological advancements like the steam press, stereotyping, and railway distribution helped encourage a wide readership. Many authors, editors, and scientists donated their contributing efforts, further reducing production costs and keeping prices affordable.

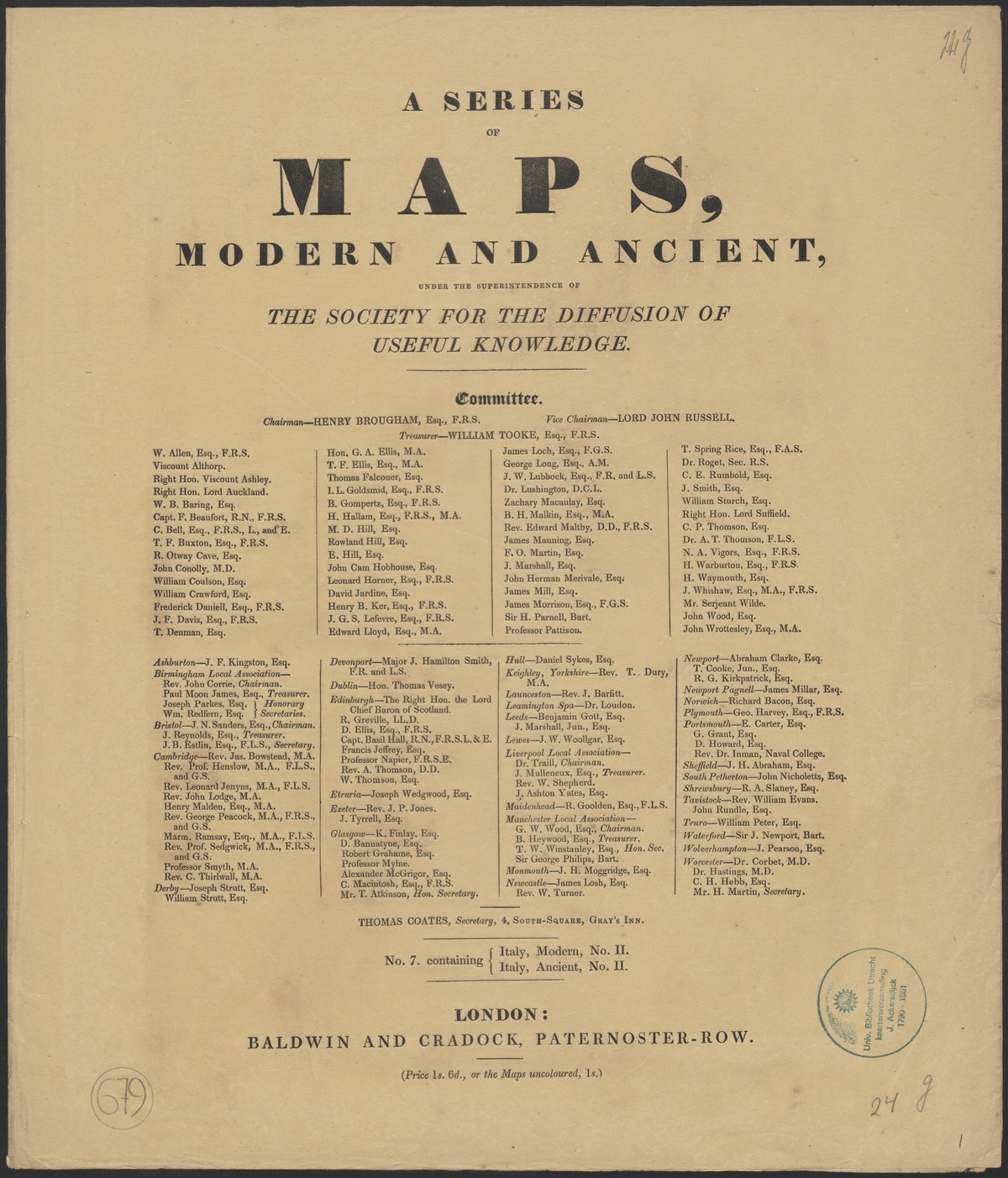

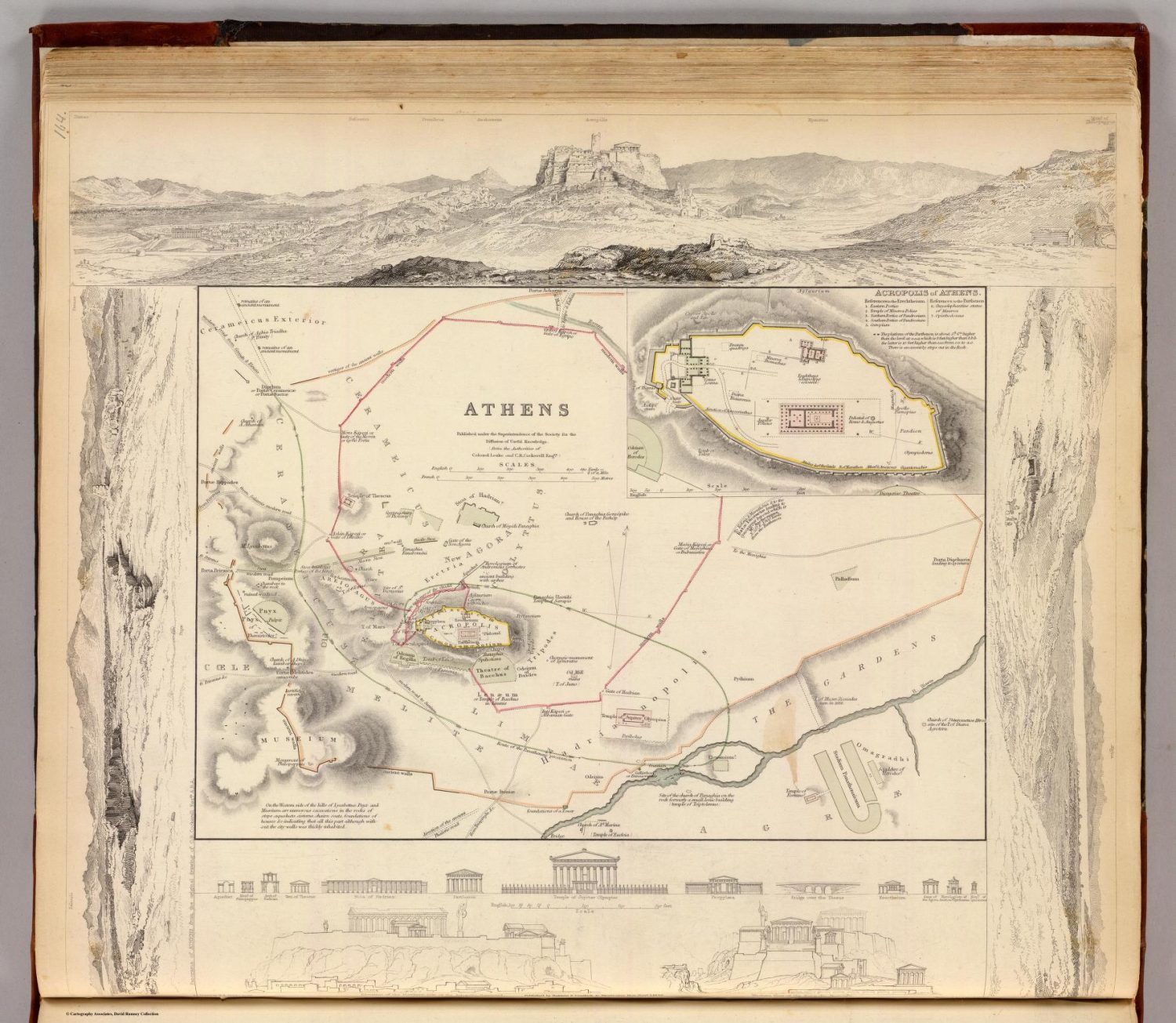

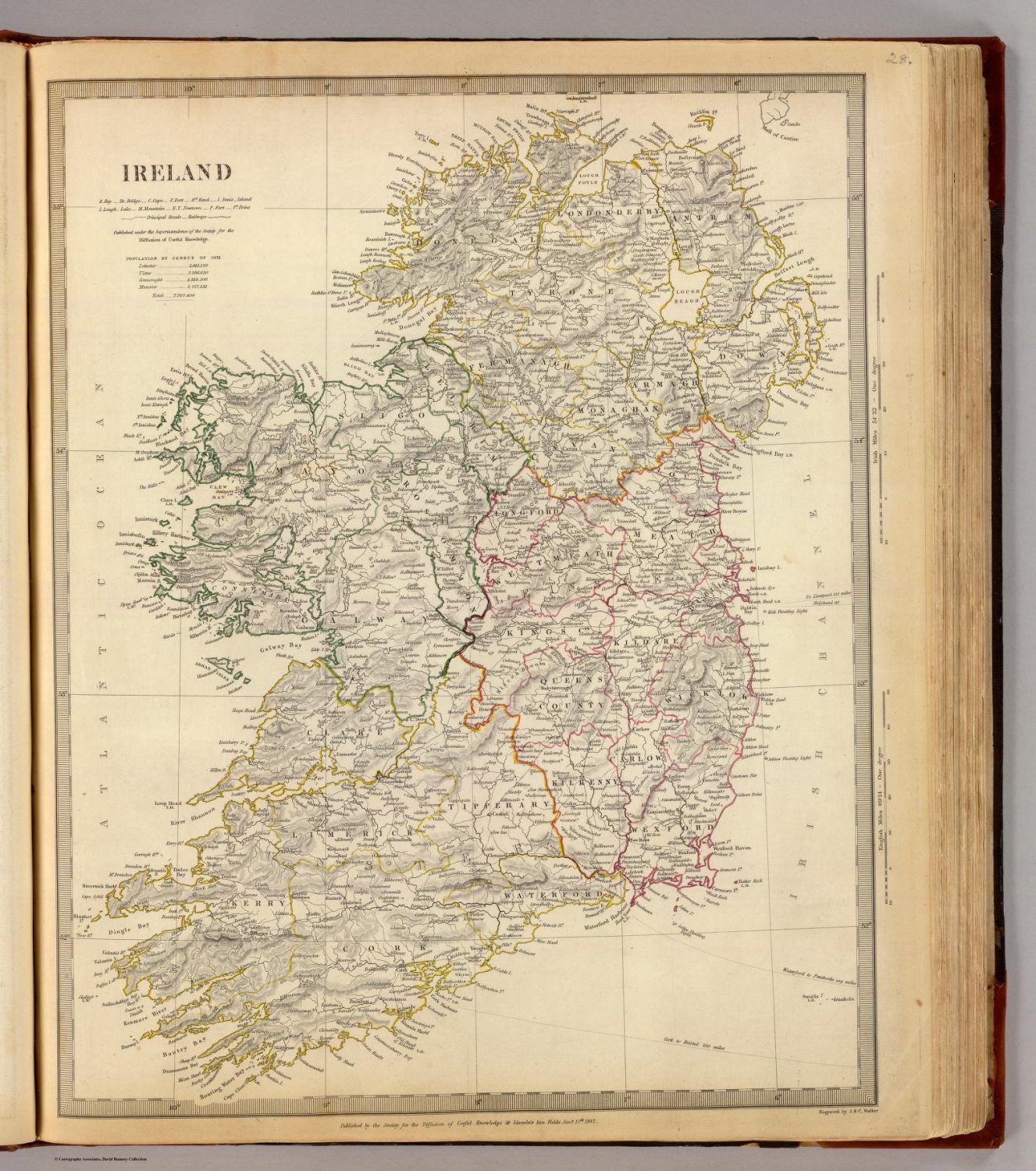

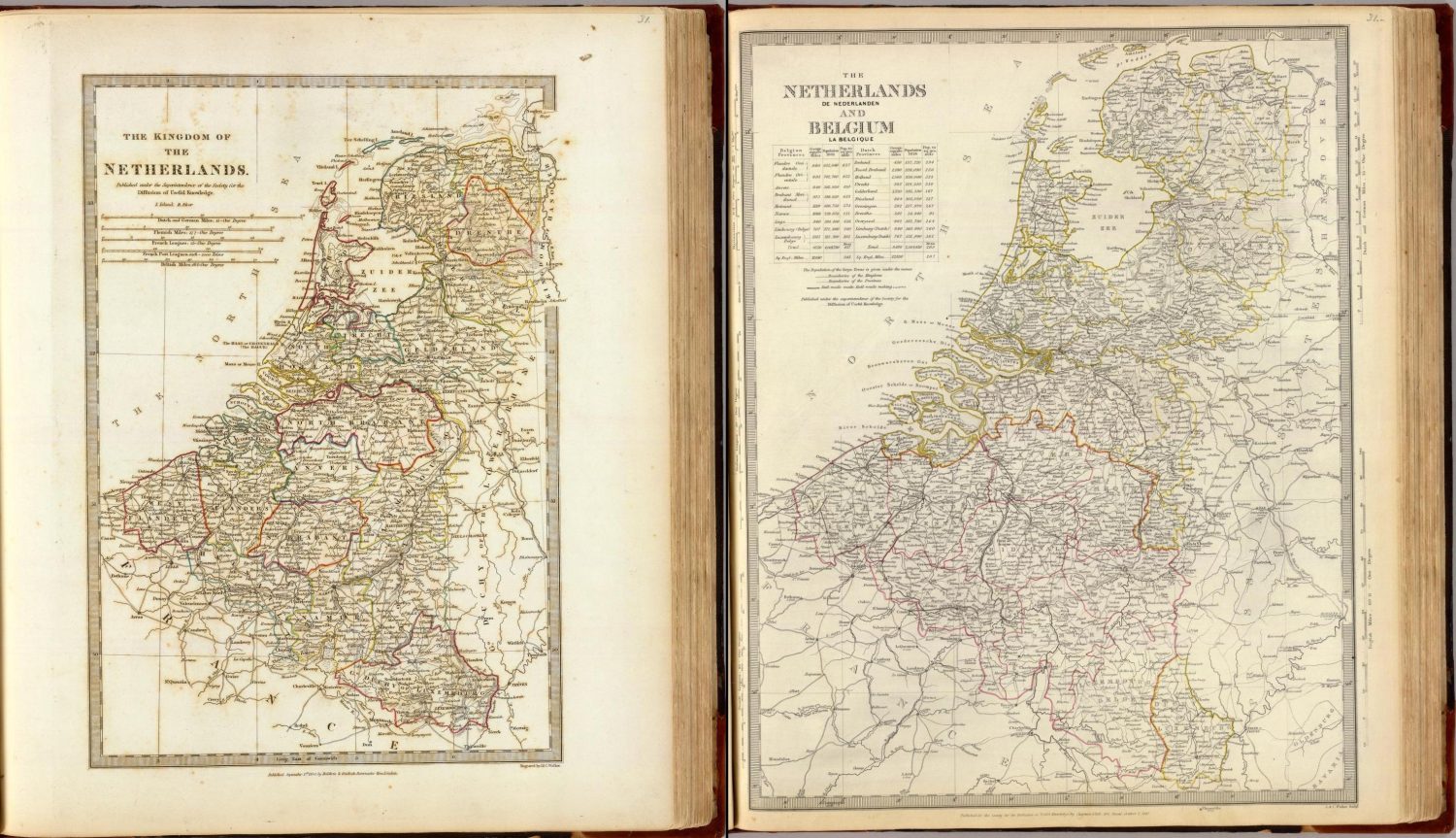

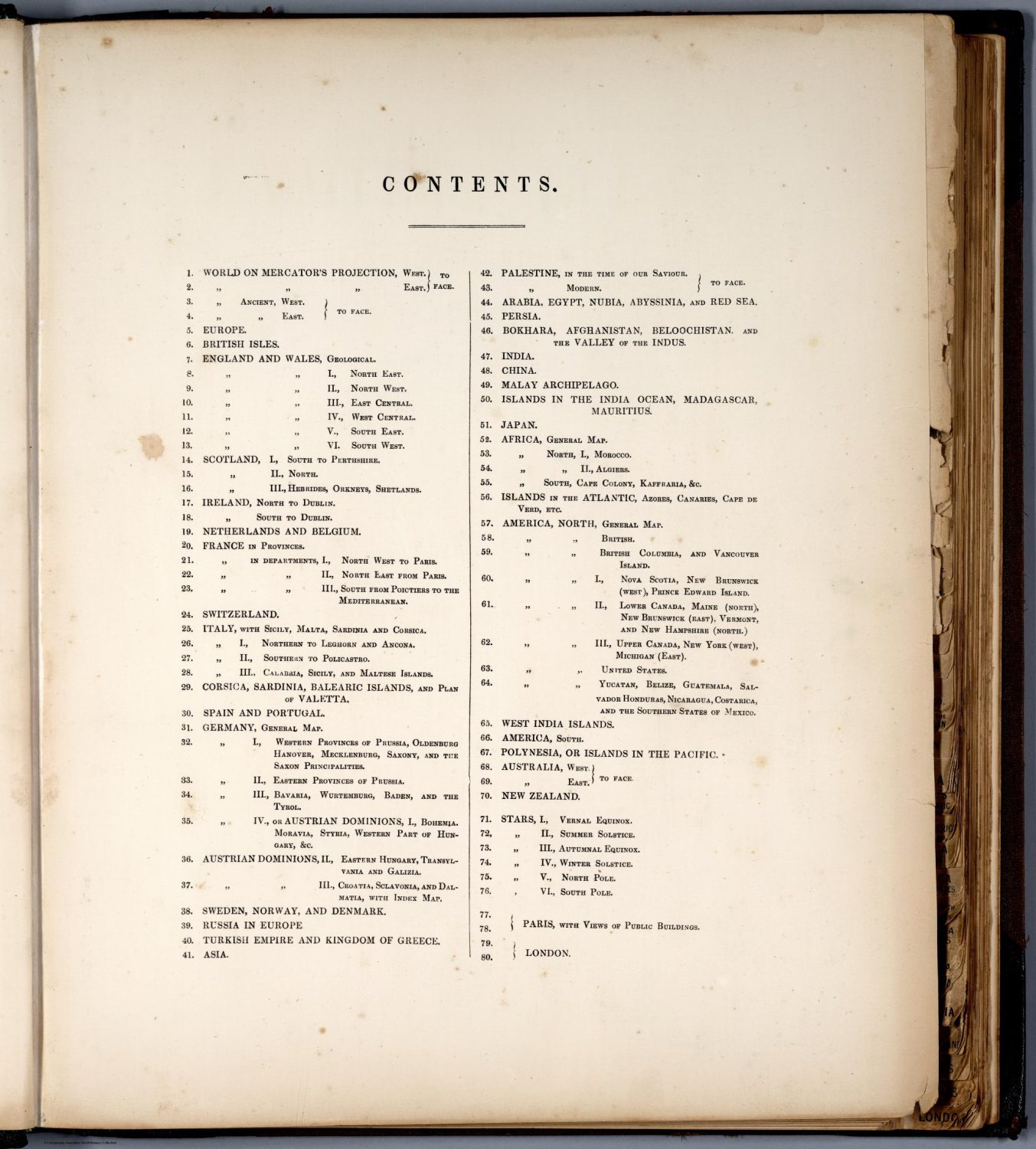

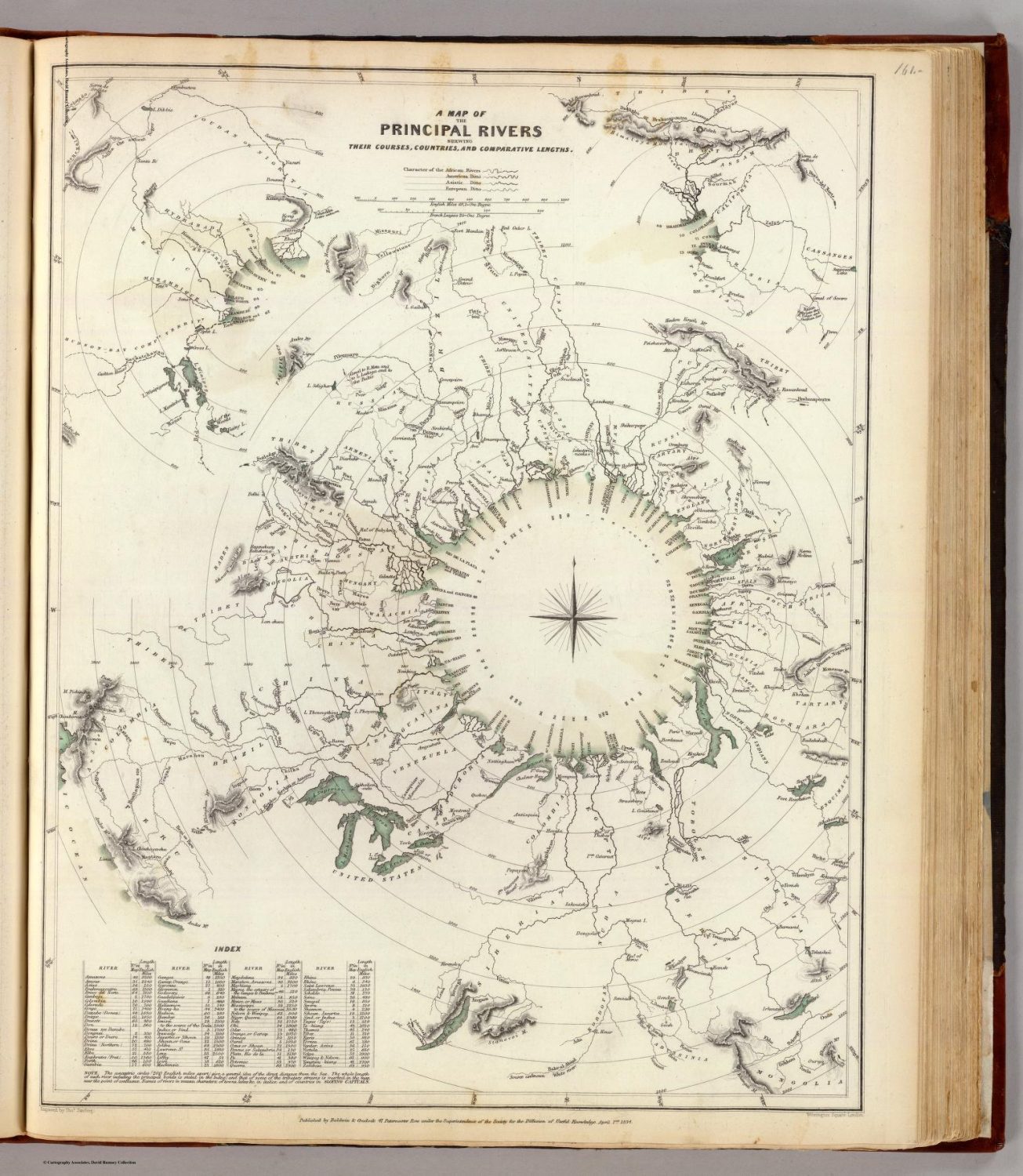

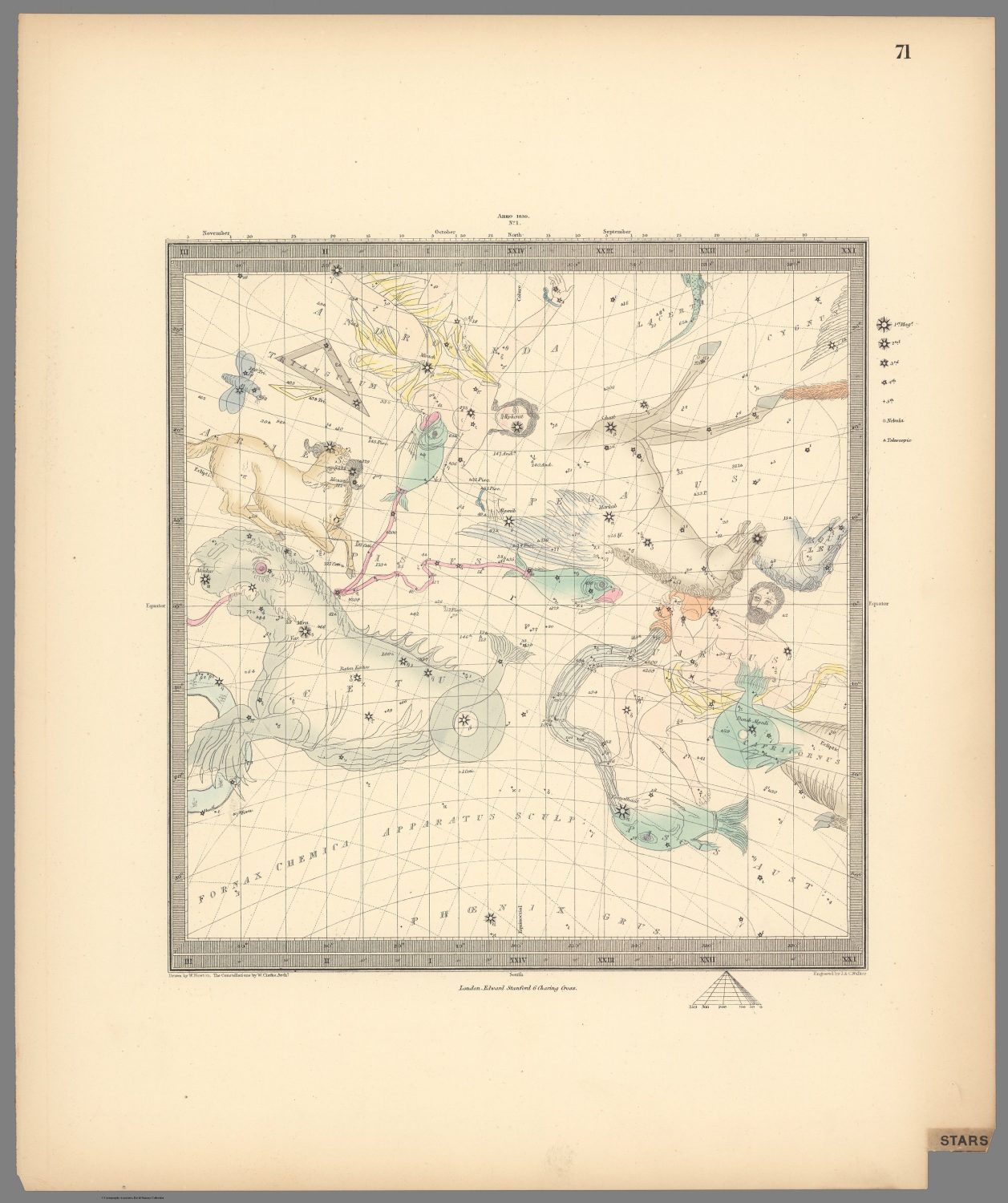

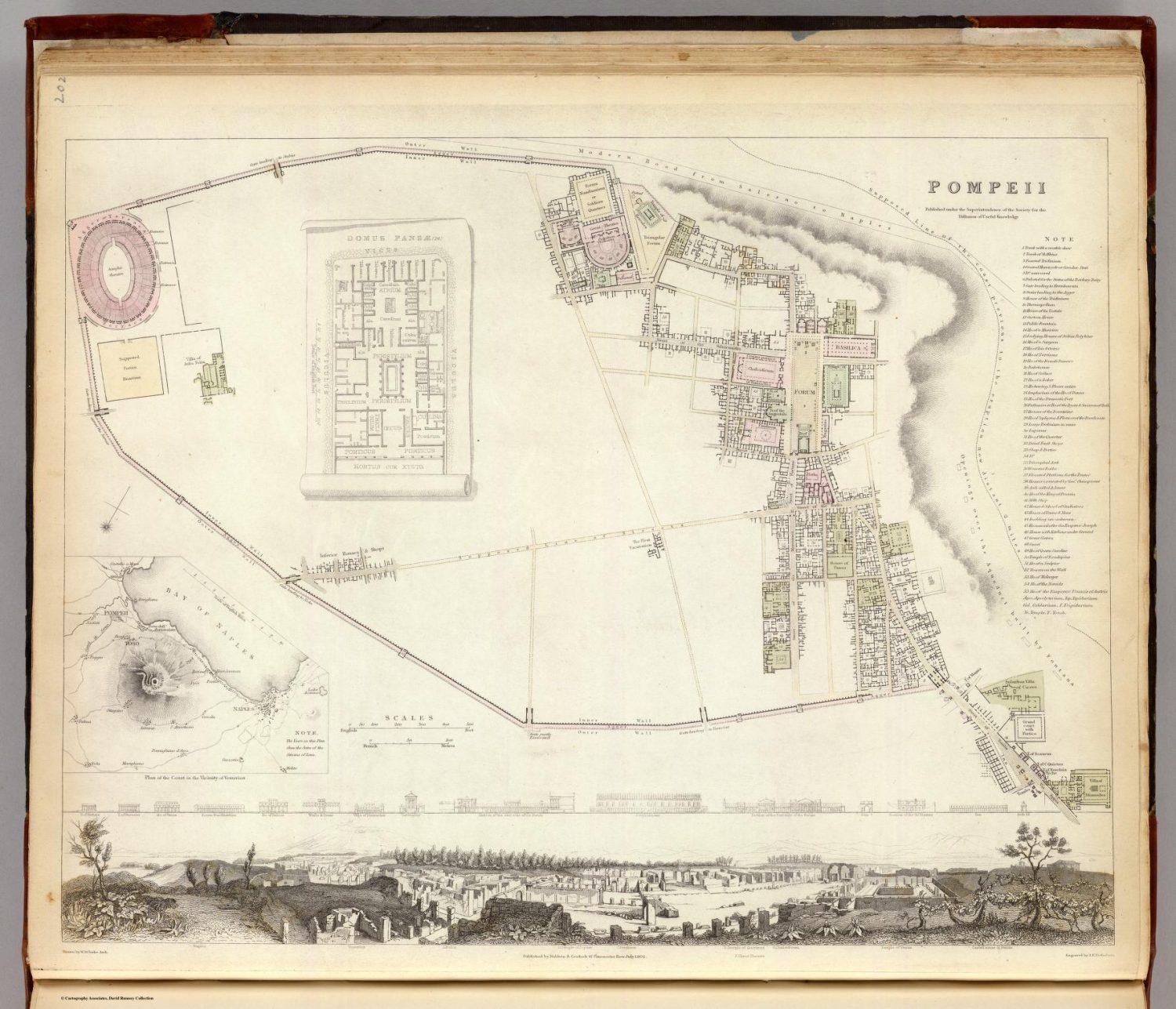

Maps were of particular interest to a contemporary audience as the British Empire began to expand its footprint across the globe. Most atlases were prohibitively expensive for the typical consumer due to their elaborate construction and production methods. An official Map Committee of the S.D.U.K. was established in 1828 to help remedy this situation. It was to be led by Captain (later, Rear Admiral) Francis Beaufort, an experienced and intelligent sailor and cartographer who served as the Hydrographer of the Navy for over a quarter century. Plans for a modest atlas containing about 25 plates quickly developed into a more ambitious goal. When the first maps (Ancient and Modern Greece) were distributed in 1829, the accompanying prospectus promised at least 50 plates. In the end, the S.D.U.K. map series would encompass 209 different plates of unprecedented detail and scope across its fourteen-year production history.

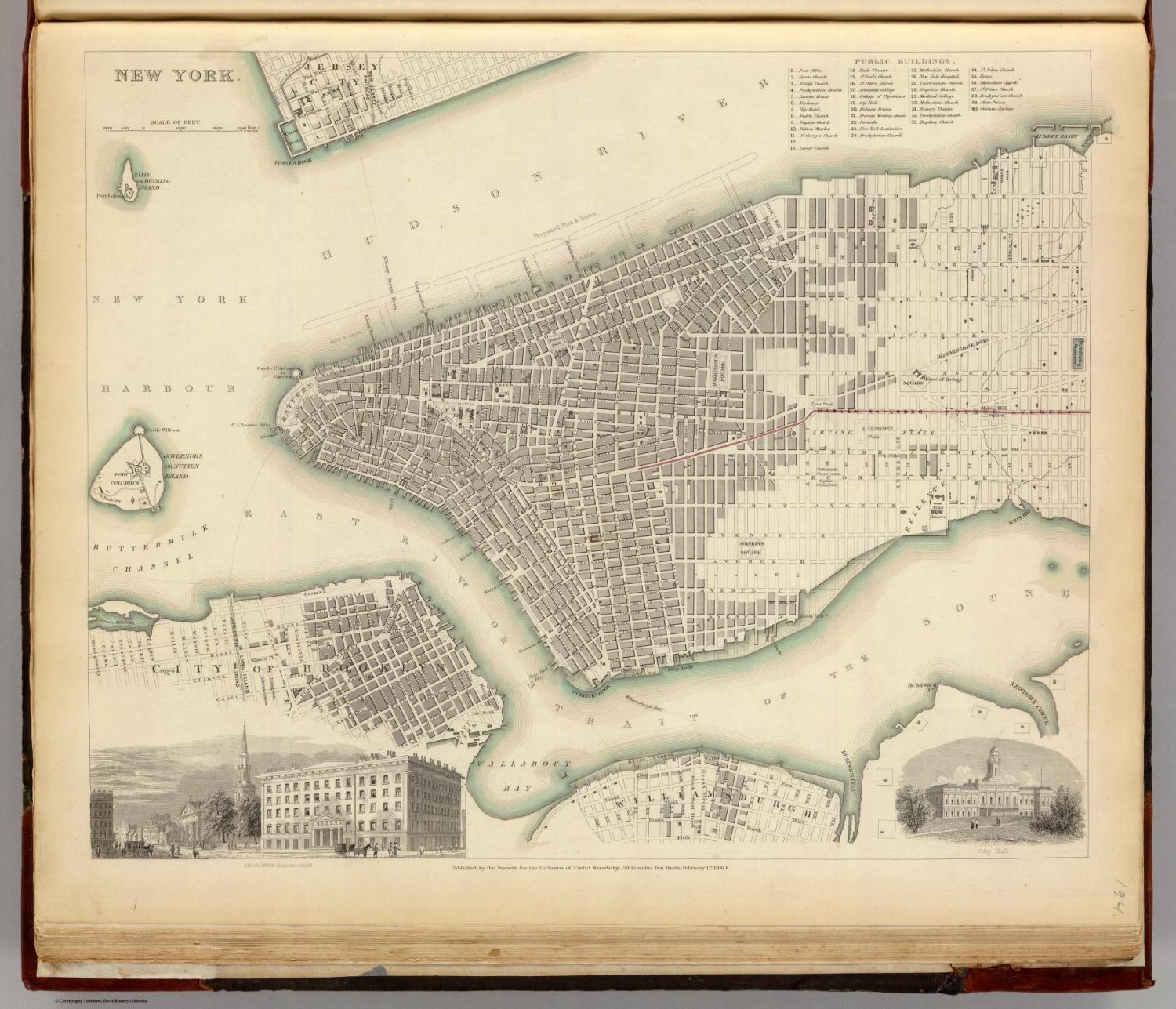

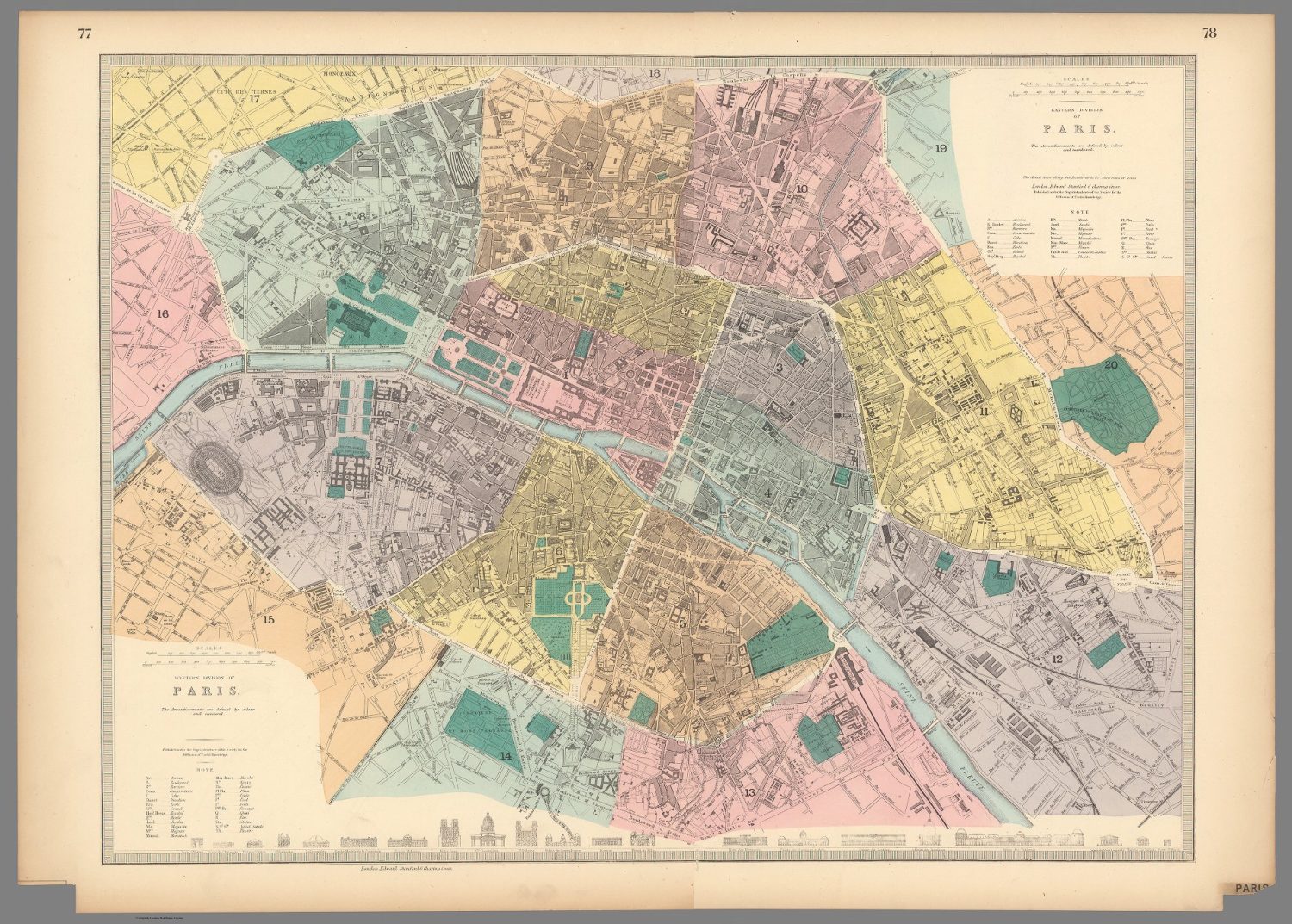

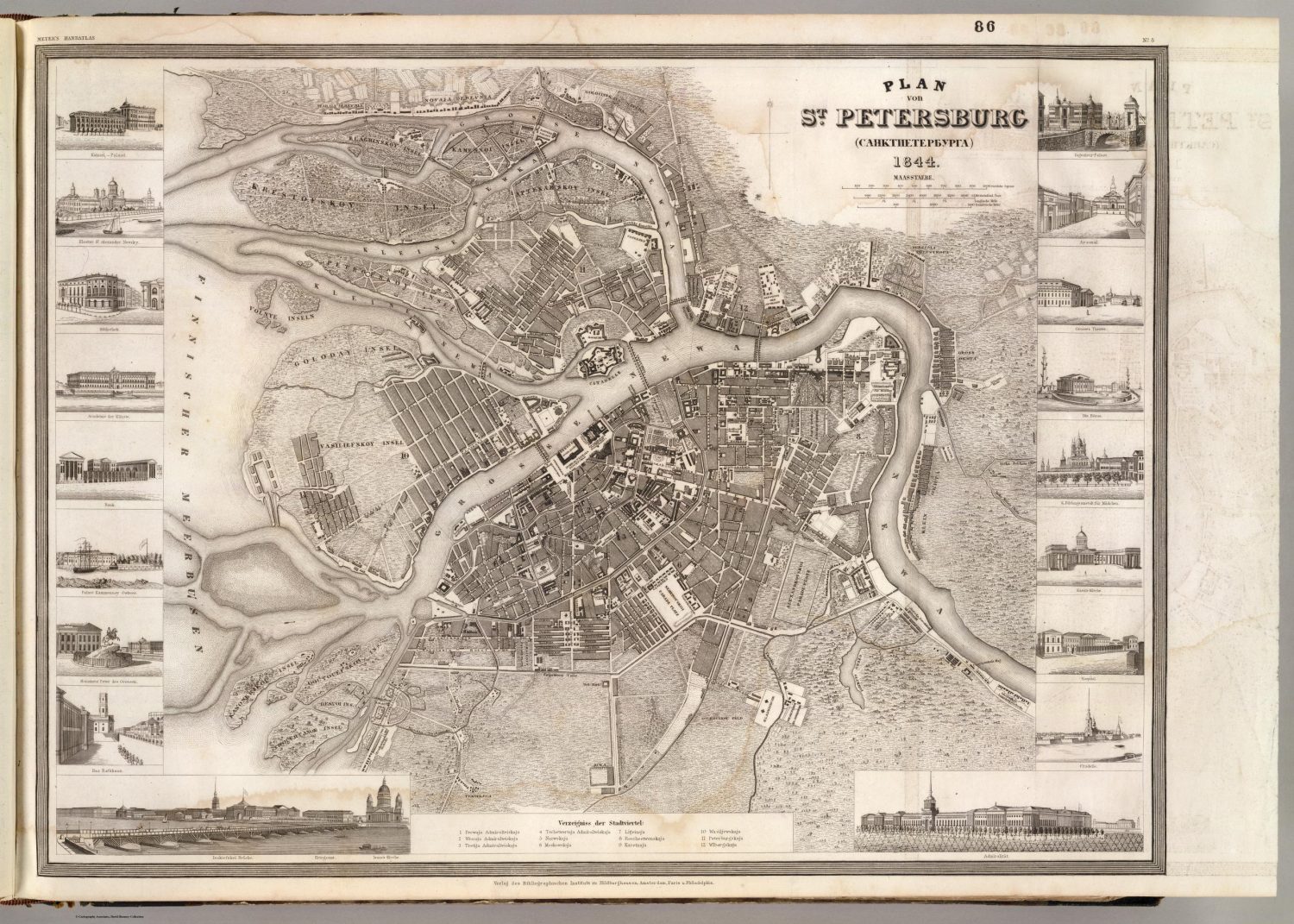

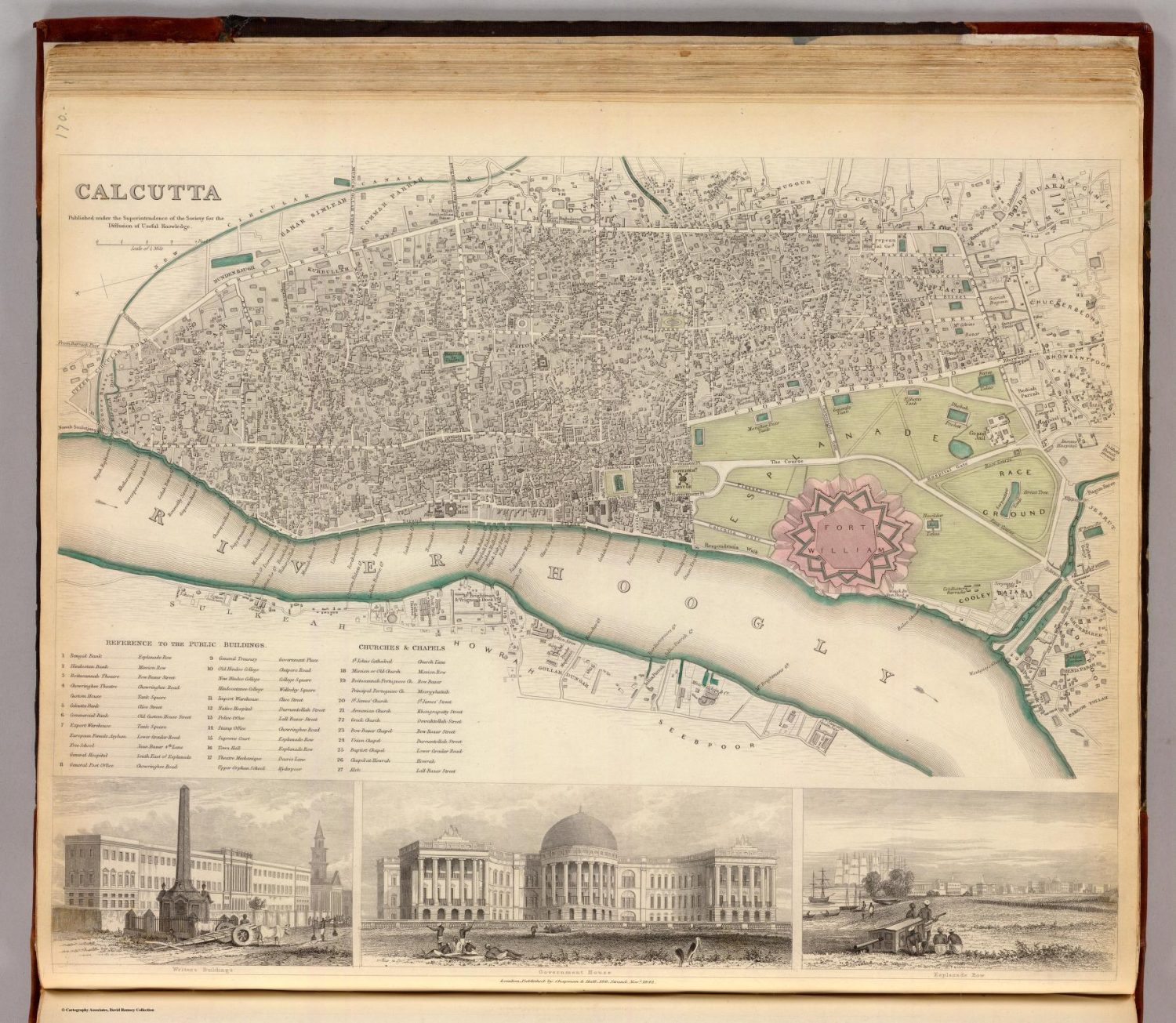

The maps were engraved on steel and initially sold on a subscription basis in pairs, known as Numbers, for one shilling each (outline color cost an extra sixpence). The aim was to release six Numbers (twelve maps) per year until the entire Map Series was complete. Decorative elements, vignettes, and engraved scenes often accompanied each image. As mentioned above, Number 1 (1829) contained maps of Ancient and Modern Greece within a paper wrapper. Number 2, released the following year, was less geographically congruous and included maps covering parts of Turkey and the Italian peninsula. This lack of coherence highlights an interesting publishing quirk – subscribers had no idea what or when each map would be released. Often, maps covering an entire country would only come after its constituent parts have been completed. For example, although the first sectional map of Italy was available in 1830, it would be another decade before the general map of the country was released. City plans (51 in total) began to ‘randomly’ appear in Number 9, further frustrating buyers looking to obtain a complete, sequential atlas of the world within a reasonable period of time. Though they were considered a distraction at the time, these fine plans are among the most desirable of the S.D.U.K. maps in the collecting market today.

Part of the delay in the completion of the Map Series was due to the uncompromising attitude and exceedingly high standards of Francis Beaufort. He wanted to ensure that every map was as accurate and as up-to-date as possible, and as Hydrographer to the Navy, he had access to many of the latest available sources. He personally edited every map issued by the Series and created many of them from scratch. For example, the two-part map of Ireland (Beaufort’s home country) took over six years for him to complete! The results were among the most detailed and comprehensive geographic depictions of the age, though the ornamentation varied.

Other issues arose with the complex publication agreements between the S.D.U.K and its partners. To keep prices low, a convoluted financial deal was struck with the publishing firm of Baldwin & Craddock. The S.D.U.K. would design and engrave the maps, while the publishers would provide printing, coloring, and distribution of the Numbers. Unfortunately, the company went bankrupt in 1837, and the following year, the S.D.U.K. took on the additional responsibilities themselves. This ended up being too much work, and Chapman and Hall were engaged in 1842 to resume where Baldwin & Craddock left off. This partnership faltered as the new printers failed to meet the exacting standards of Beaufort and others on the Committee. Litigation ensued, but wouldn’t be resolved until 1844, by which time the Map Series had finally been completed. Charles Knight, publisher of the Penny Magazine, provided the map publication services until 1846, when the S.D.U.K. voted to suspend operations and effectively shutter their doors.

Although the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge disbanded only a few years into Victoria’s reign, its impact would be felt throughout the era. During its two decades of operation, the S.D.U.K. printed and sold over 3 million maps from the Map Series – approximately 15,000 atlases’ worth, according to Mead Cain. These would have helped to expand knowledge about the geography of the world, past and present, to an enormous audience in Britain and abroad. Several maps provided up-to-date information on contemporary events, such as the siege of the Portuguese city of Porto (1832-1833) and the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845).

Furthermore, the life of the maps would be extended long after the S.D.U.K. had closed. Charles Knight purchased the steel plates from the Society for £4500 in 1846 and completed a revision the following year. He would continue to publish single maps and full atlases until 1852, at which point he then sold the plates to George Cox. They then passed to Edward Stanford in 1856, who again created new editions between 1863 and 1865. Thomas Letts took over the publication of the S.D.U.K. maps from 1877 until 1885, when his insolvency led to their purchase by the firm of Mason & Payne. These new owners would continue to issue maps until around 1889, capping a 70-year print run. Because of their incredible longevity, the maps of the Society for the Diffusion Knowledge were among the most widely consumed in 19th-century Britain – truly, Maps for ‘The Million.’

S.D.U.K. maps available for sale on my website can be found here.

Sources.

Allen, Phillip. The Atlas of Atlases. ABRAMS, 1992.

Ashton, Rosemary. “Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 24 May 2008, doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/59807.

Cain, Mead T. “The Maps of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge: A Publishing History.” Imago Mundi, vol. 46, no. 1, Jan. 1994, pp. 151–167, https://doi.org/10.1080/03085699408592794. Accessed 24 Nov. 2021.

Johansen, Thomas. “Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge.” Histecon.fas.harvard.edu, 1 Jan. 2017, histecon.fas.harvard.edu/visualizing/sduk/. Accessed 28 Mar. 2023.

McAlhany, Joe. “Old World Auctions – the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge.” Www.oldworldauctions.com, 1 Mar. 2017, www.oldworldauctions.com/info/article/2017-03. Accessed 28 Mar. 2023.

Ronald Vere Tooley. Tooley’s Dictionary of Mapmakers. Tring, Eng. : Map Collector Publications, 1979.

St. Onge, Tim. “Maps for the Masses: Geography in the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge | Worlds Revealed.” The Library of Congress, 13 July 2016, blogs.loc.gov/maps/2016/07/maps-for-the-masses-geography-in-the-society-for-the-diffusion-of-useful-knowledge. Accessed 28 Mar. 2023.