It’s no secret that I’m a fan of transportation maps, especially those published during the first half of the 20th century. Such a short period of time saw greater changes to human mobility than any other span in history. The widespread adoption of the airplane and automobile allowed for an entirely new traveling and tourism experience – one that often required assistance in the form of guidebooks and maps.

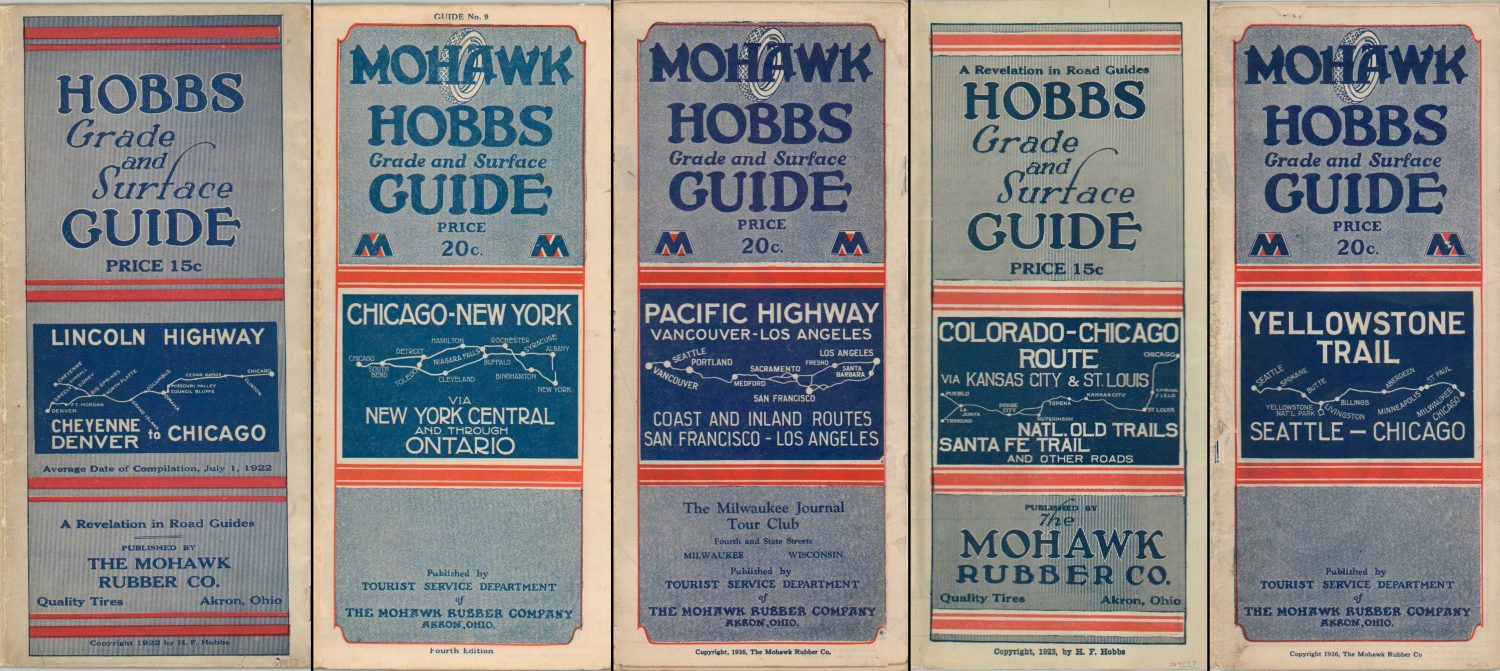

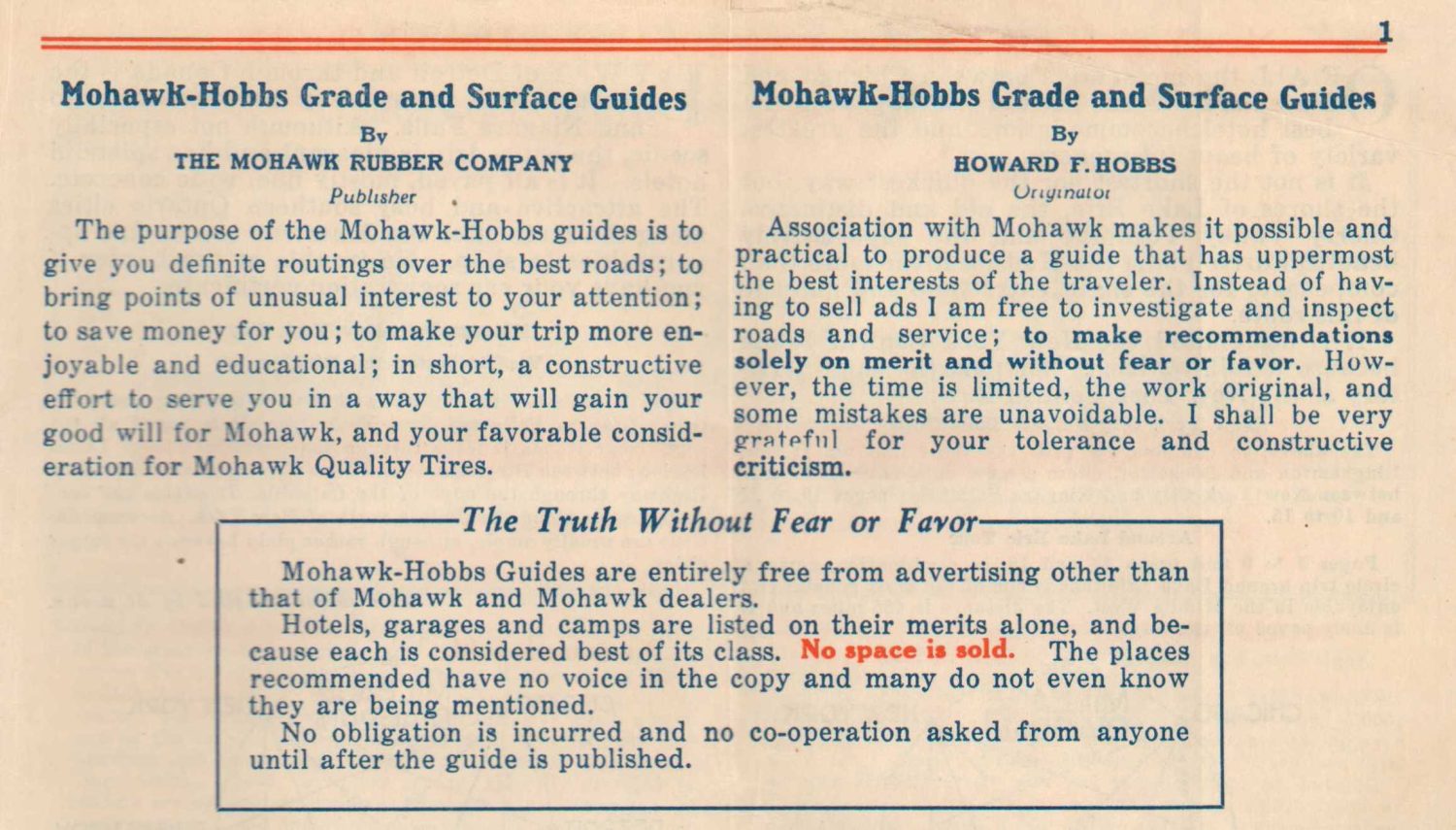

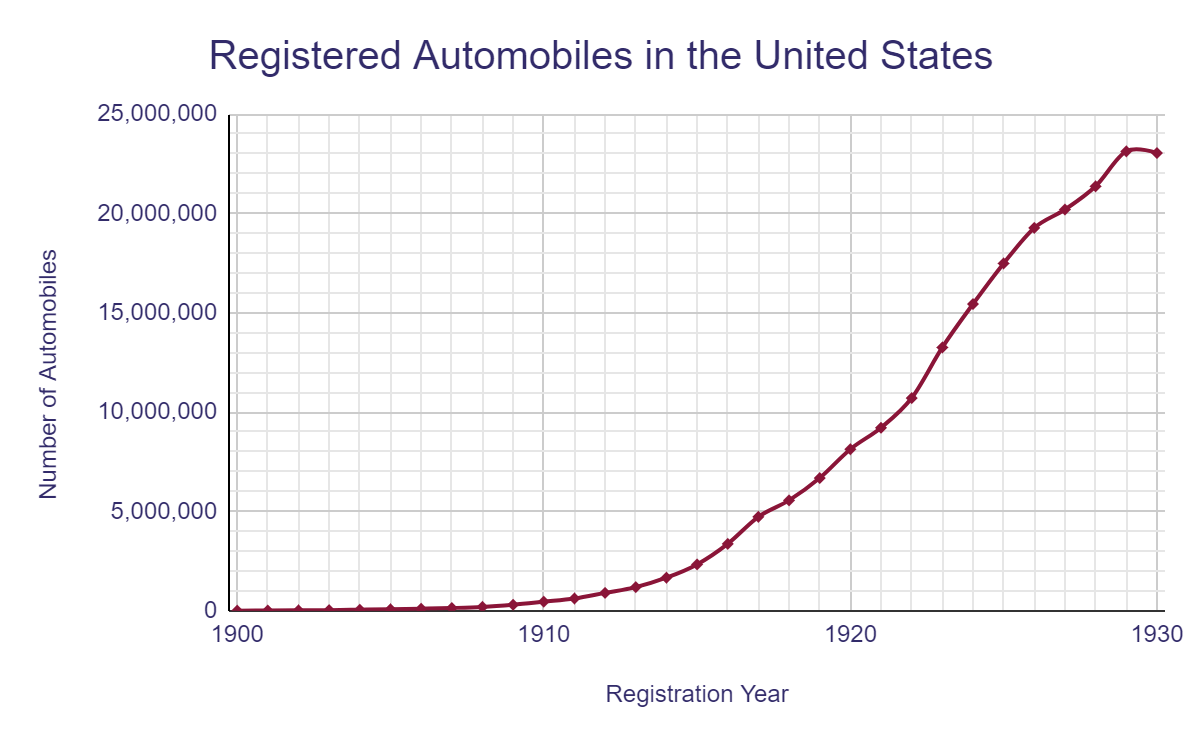

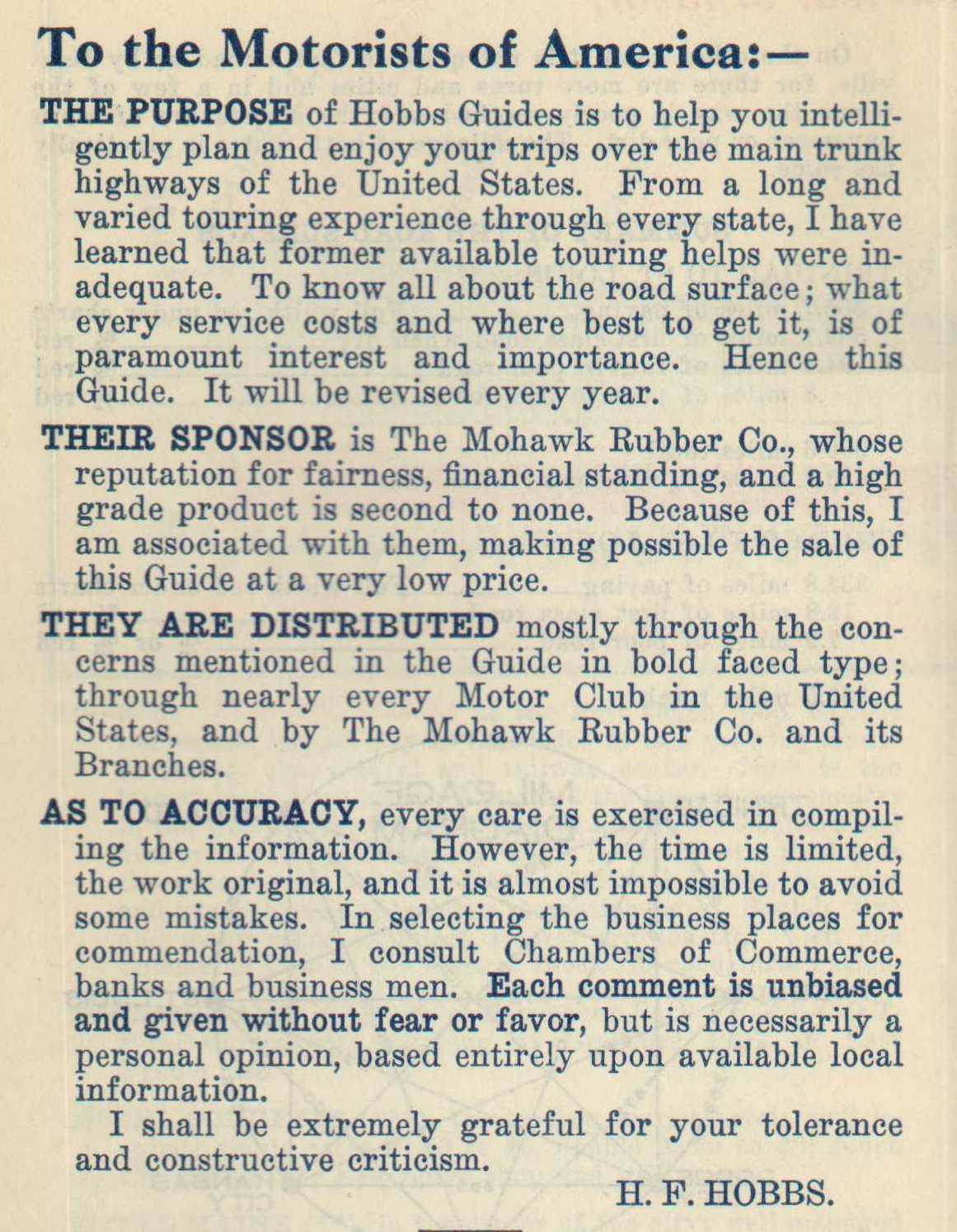

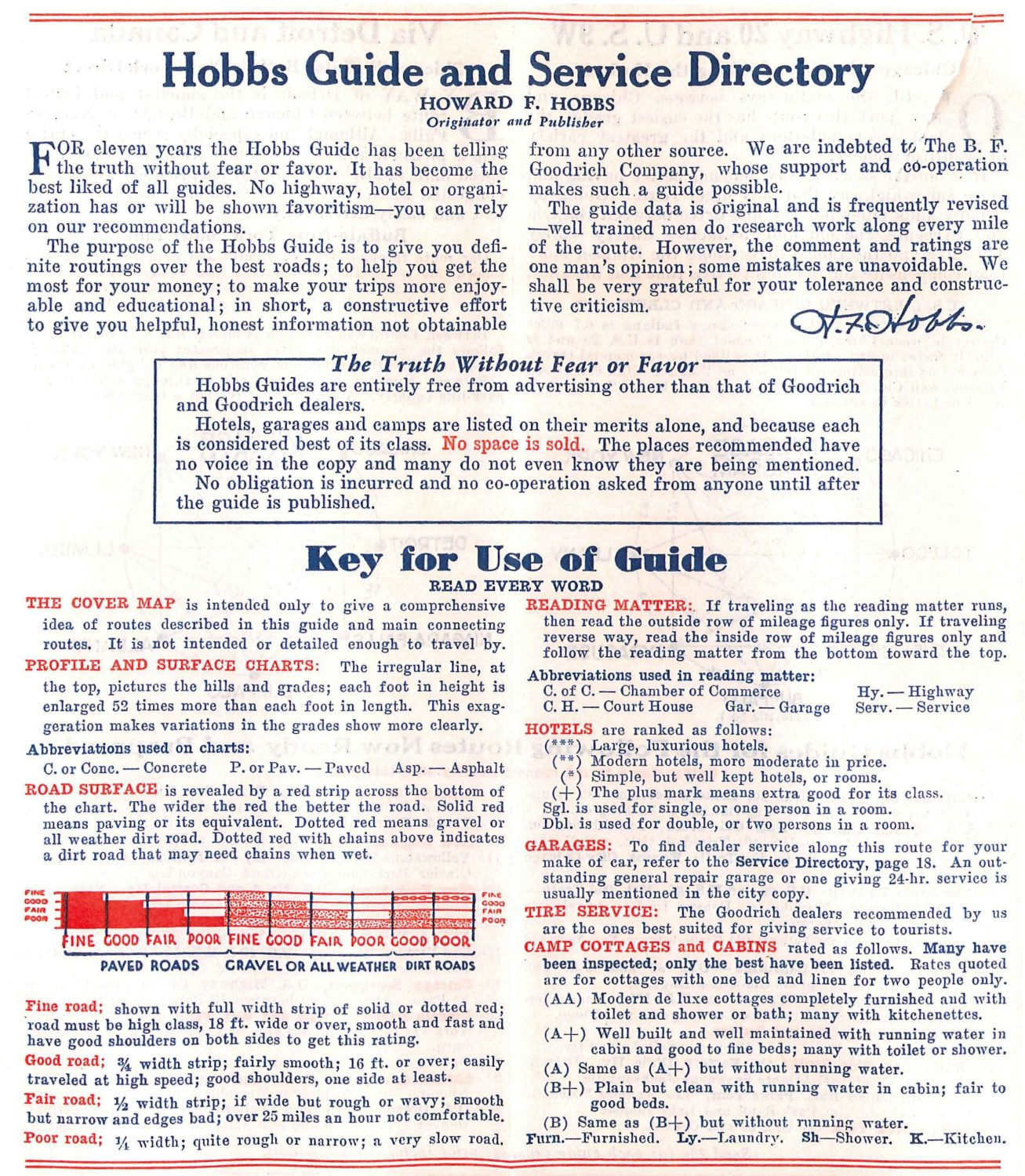

One of my favorites is a series of Road and Surface Guides created by Howard F. Hobbs and published in Akron, Ohio by the Mohawk Rubber Company from 1922 to c. 1933. Hobbs pioneered the inventive design but needed a financial partner to make the guides affordable. Mohawk was operating in a crowded field of local competitors that included B.F. Goodrich (who also issued maps and guidebooks), Firestone, and Goodyear. They hoped to stand out by partnering with Hobbs and distributing a novel form of travelogue that incorporated numerous different elements useful in travel planning and likely familiar to most motorists.

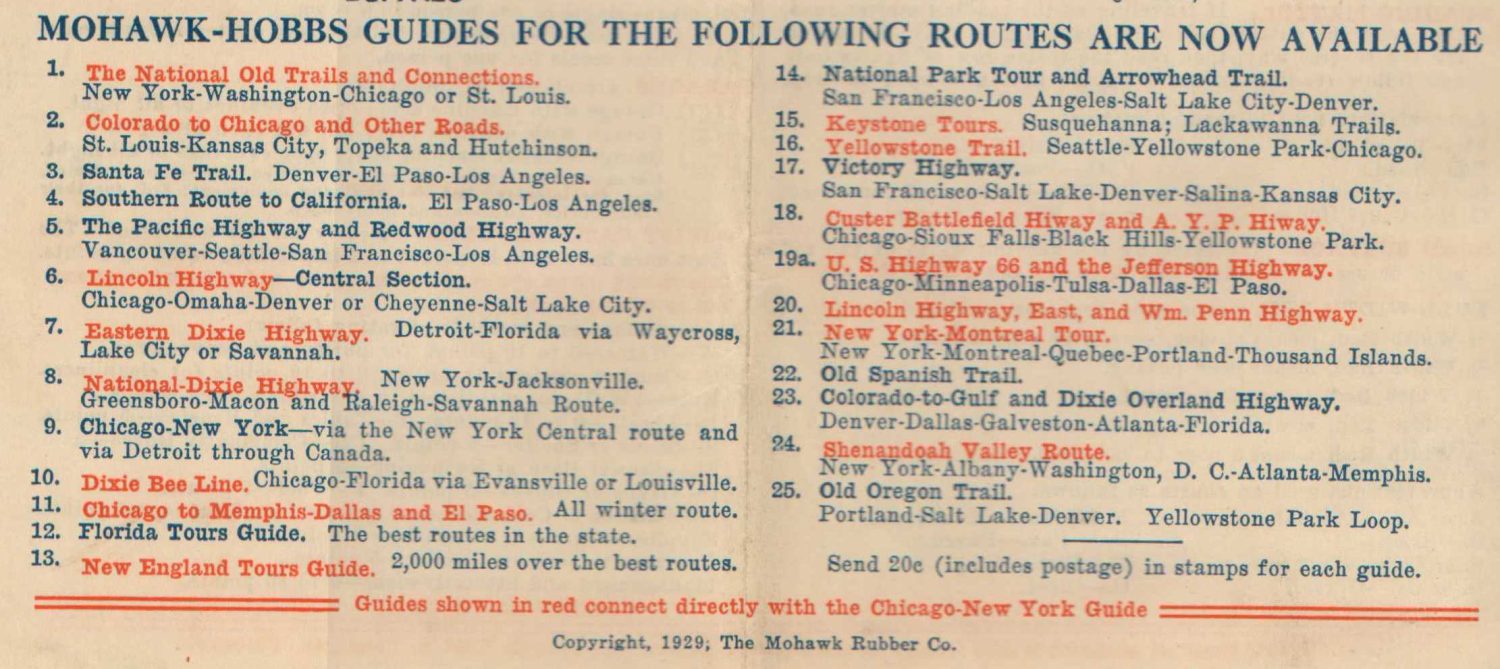

Each guidebook covers the route of a different prominent auto trail in the United States, anchored at either end by one or more major urban centers. At least 25 different examples were printed across numerous editions (revised annually), providing an in-depth overview of how these early highways developed. Over half are dedicated primarily to routes running west of the Mississippi River, though the majority of the paved roads could be found in New England during the 1920s.

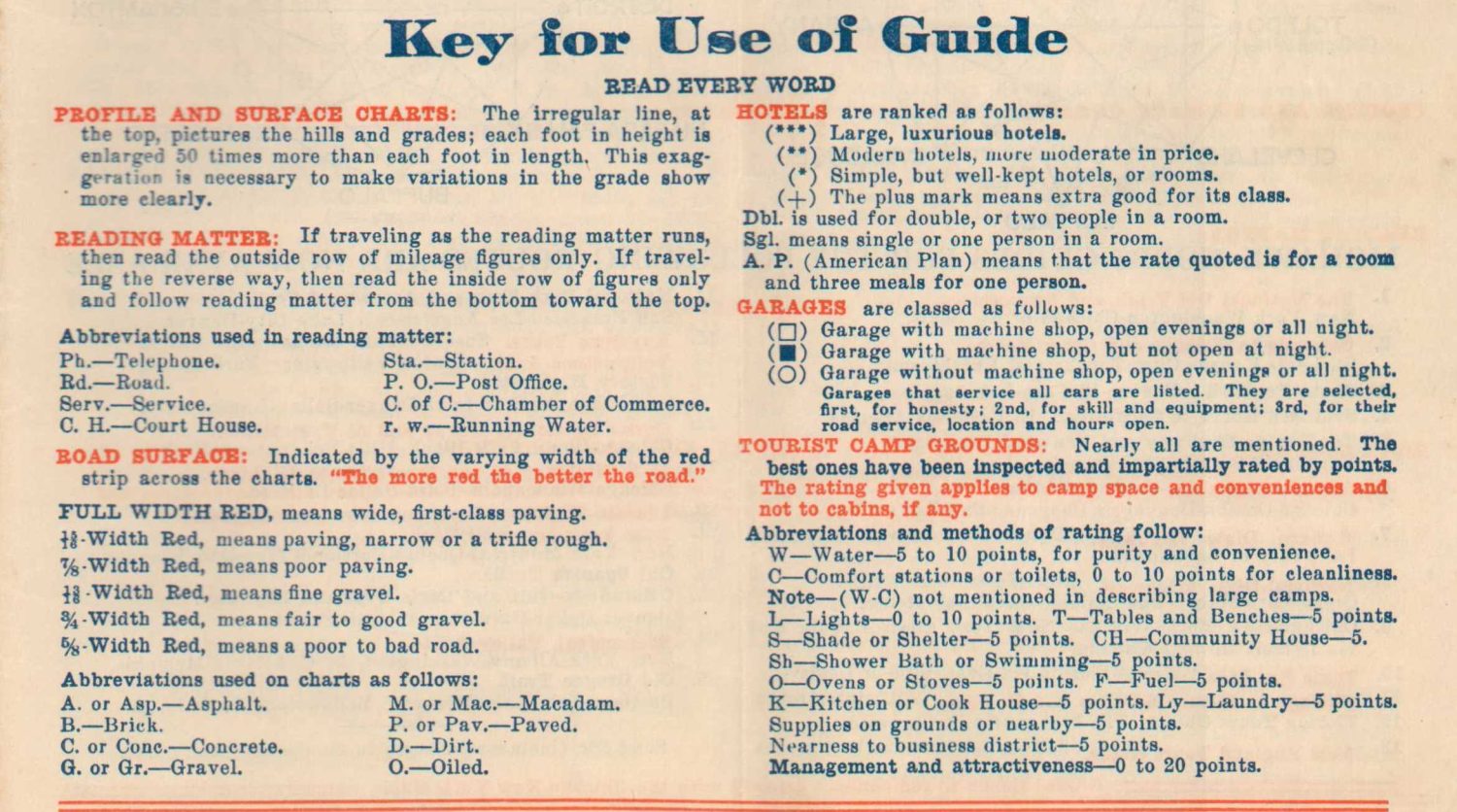

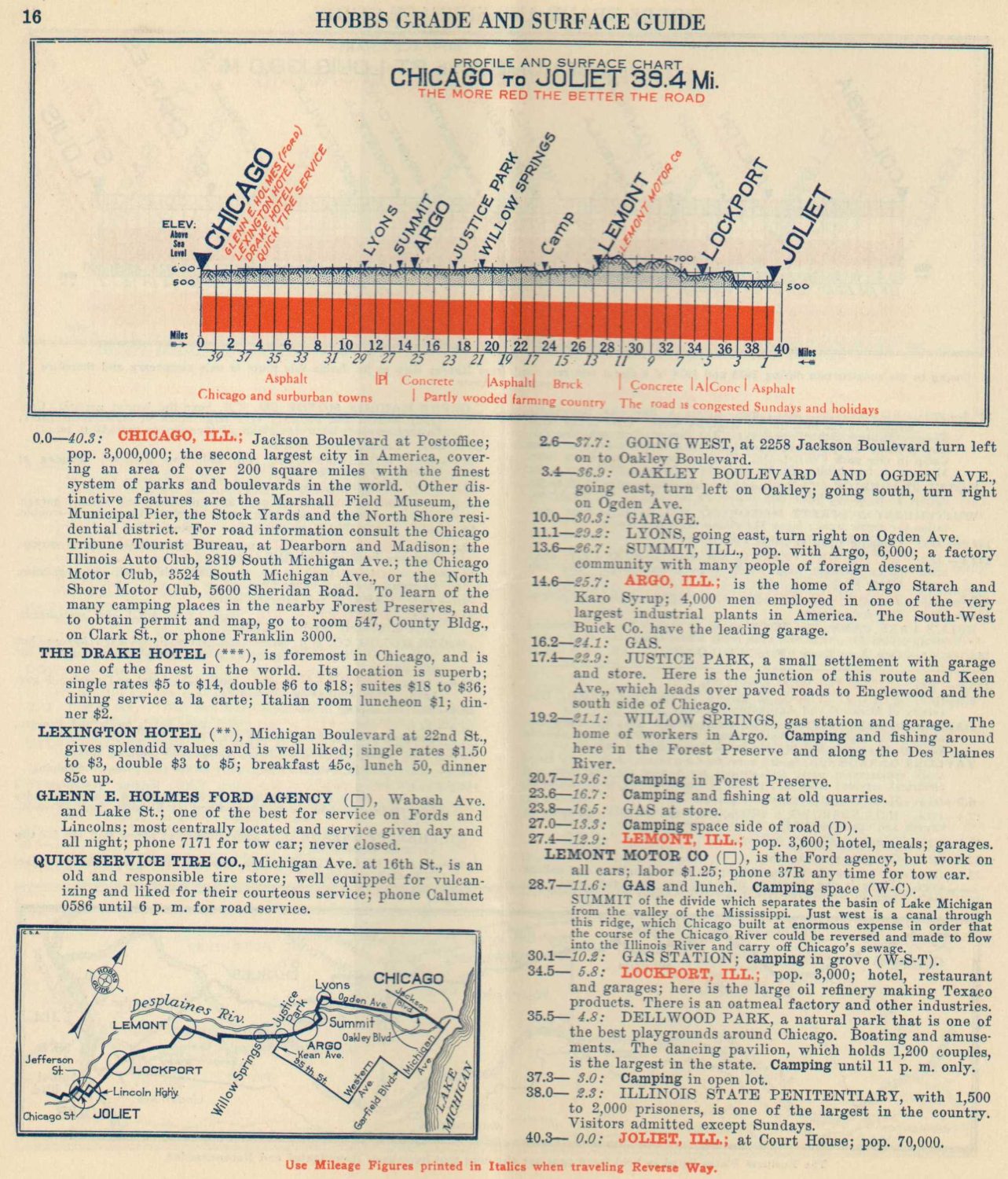

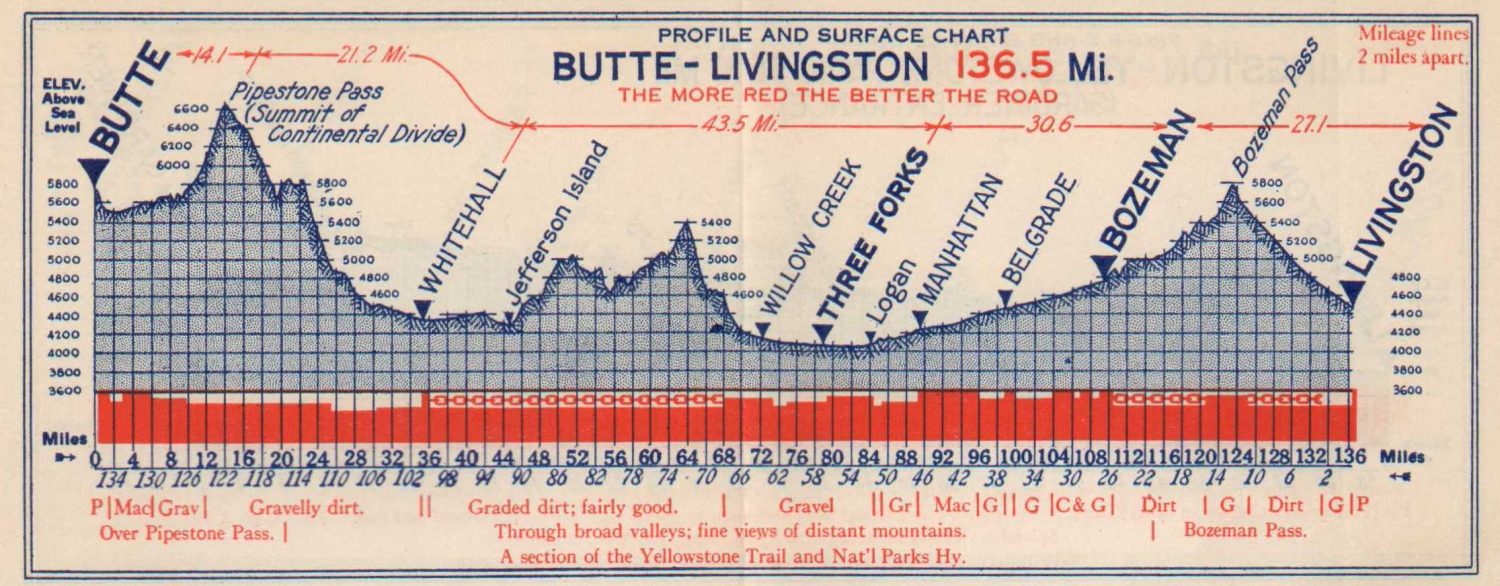

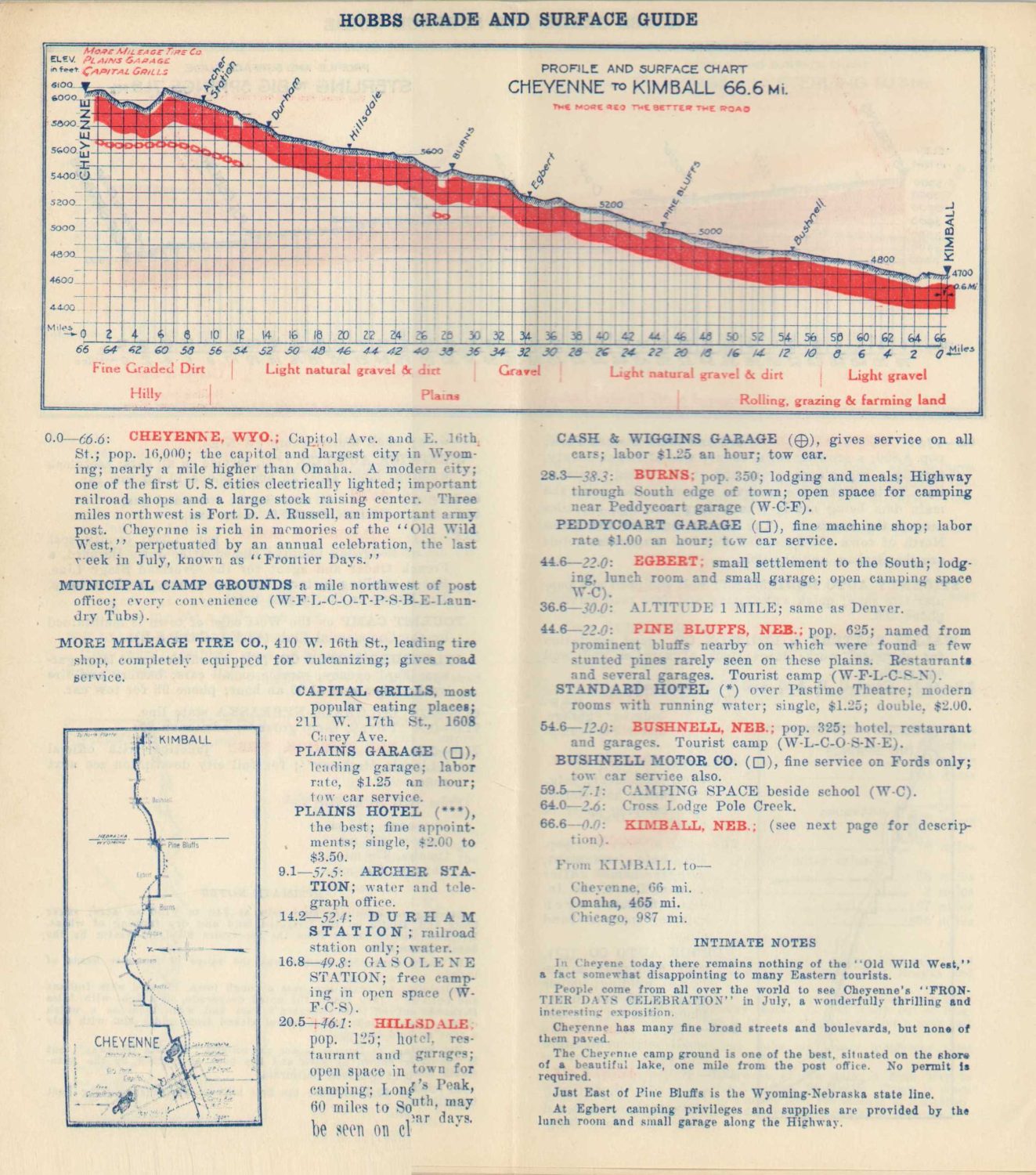

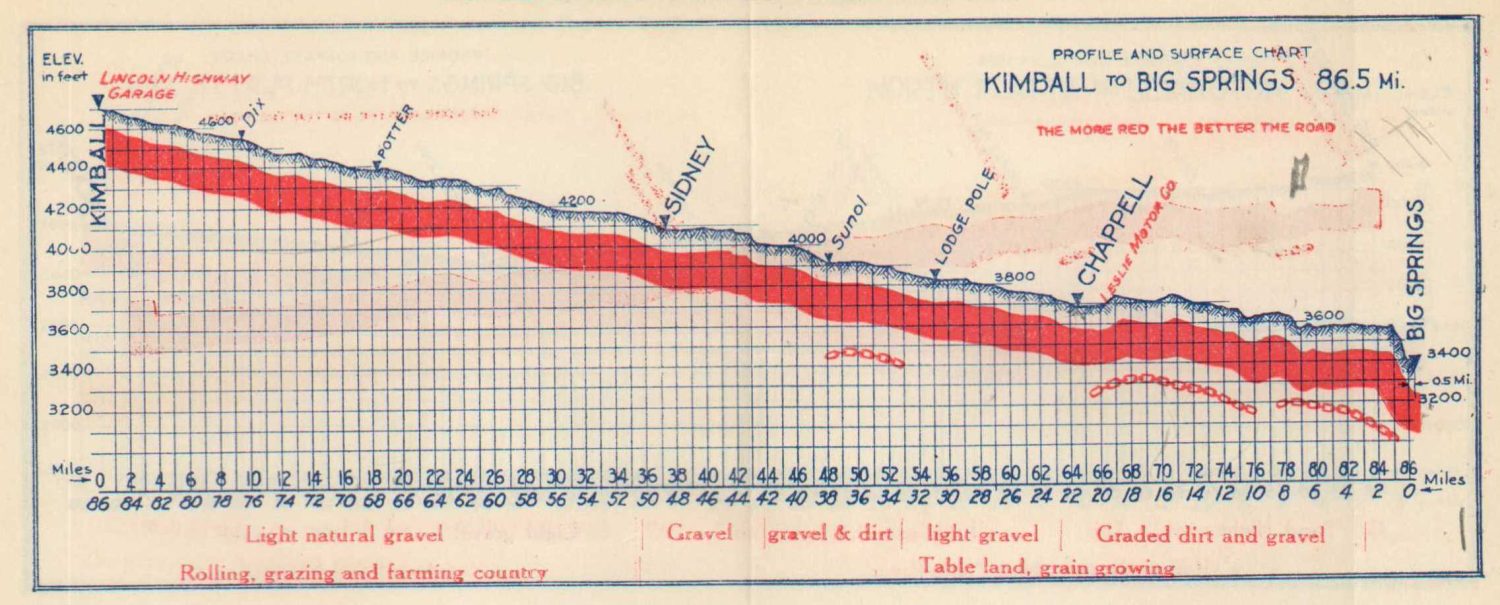

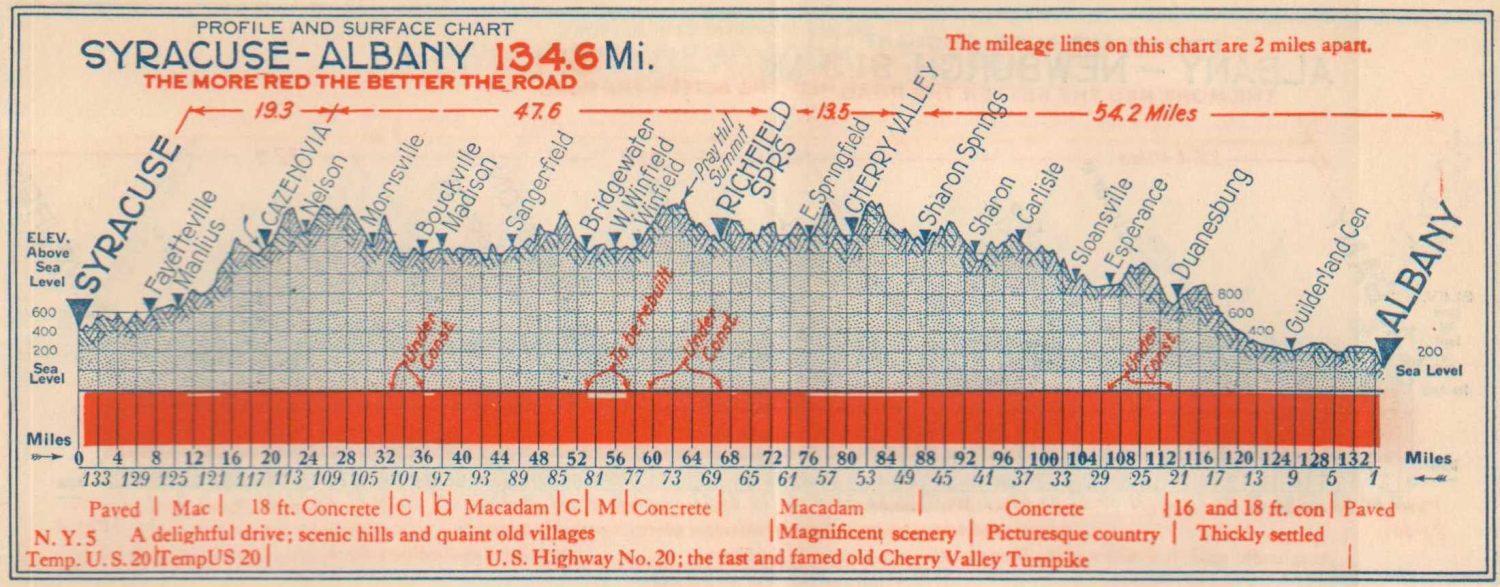

Instructions for use and a brief description of the route are followed by around 20-30 pages. Each sheet presents a segment of the trail and shows a detailed elevation diagram, a summary of the landscape, recommended facilities, a strip map, and a text itinerary.

Though none of these elements were necessarily original (written travel logs date back to the Middle Ages; both cyclists and railroads were keenly interested in in elevation), the Mohawk-Hobbs Grade Surface Guide was a ‘Revelation in Road Guides’ for how it synthesized all the information on one page.

Occassional “Intimate Notes” provide interesting insight into local features and possibly reflect personal observations of the author. Advertisments for the Mohawk Rubber Company are also sometimes included, hoping to boost sales for products like Mohawk Flat Tread Cord Tires. The bottom of each page lists a helpful tip or clarification.

At the time the Hobbs-Mohawk Guides were published, automobile usage was skyrocketing across America, though the road network remained a patchwork of dirt, gravel, brick, macadam, asphalt, and concrete. Weather was a primary concern for motorists, as surface conditions could change drastically during the rain. The frequent maintenance required for most vehicles made garages and mechanics a necessity on any long trip. Gasoline availability was a critical concern, just as it remains today.

Other motorists’ amenities were relatively limited. Restaurants were sparse and hotels operated primarily in urban centers and could be quite expensive. Outdoor campsites were the most popular form of overnight accommodation. Characteristics of these ‘motor camps’ varied greatly from place to place and the guides give a great deal of attention to their location and quality. Some of these facilities even included cabins available for rent – predecessors to the motels that would become popular during the 1930s and later.

The wealth of data presented on each page reflects and highlights these conditions. The road is represented in both form and function, allowing the intrepid driver to plan for almost any circumstance in short or long distance travel.

Distances, terrain, and infrastructure are covered in great detail, though limited to the scope of linear travel between two points along a fixed route. Additional relevant information is provided on major cities, prominent attractions (notably National Parks), and interesting excursions, where applicable. Though the maps, charts, and text appear authoritative, regularly updating the guides would have been a painstaking effort.

Accuracy was critical, especially from Mohawk’s perspective, and maintaining the guides with up-to-date information was undoubtedly difficult for Hobbs and his team (later guides are credited to different authors). Based on the language used in the introduction, it’s likely a combination of personal surveys and exhaustive correspondence was used to obtain the necessary data.

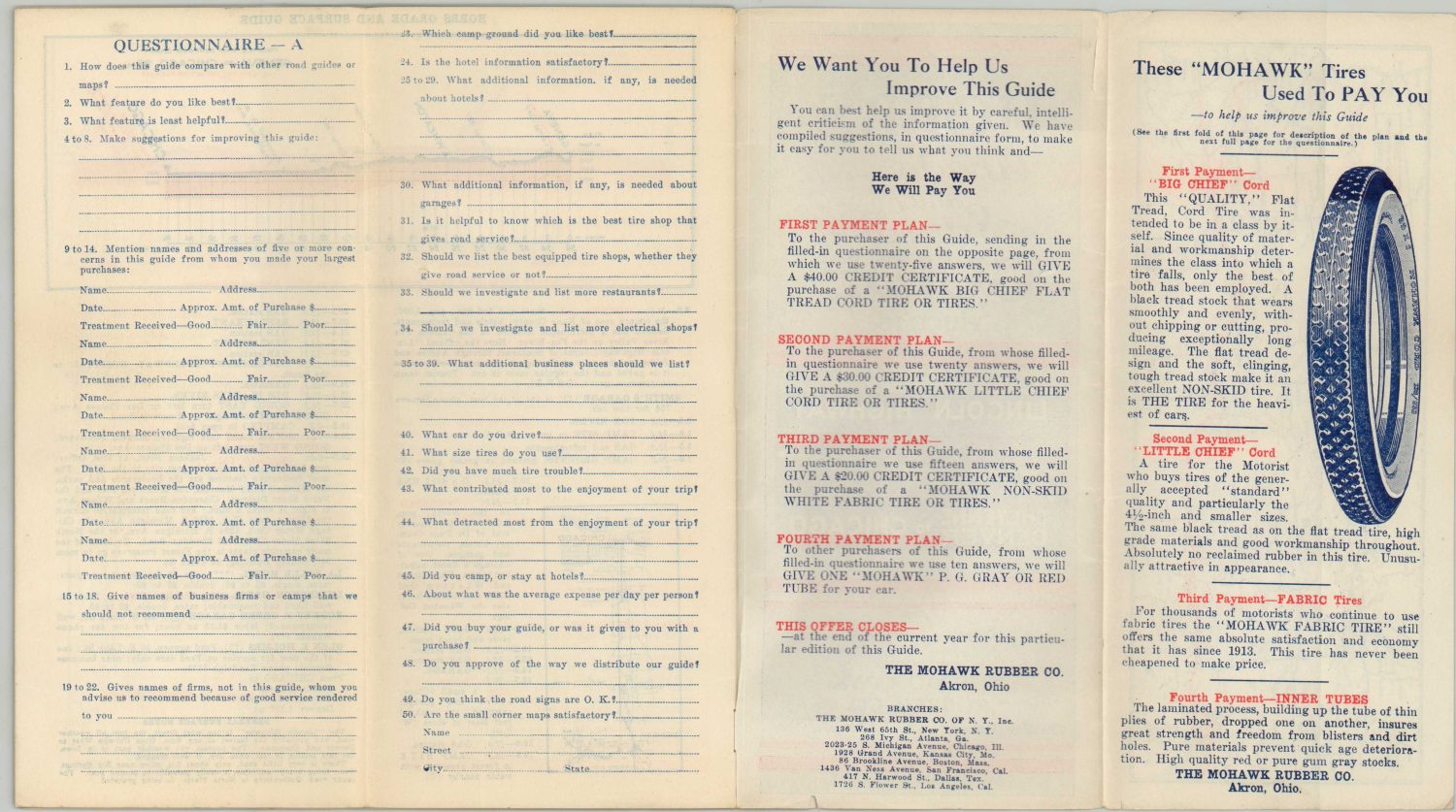

Input from local Chambers of Commerce, Highway Associations, and State Highway Departments (just beginning to develop) would have been critical. Another vital source was through user submissions. At least one early edition include a solicitation for any necessary corrections and several examples include a questionnaire in which such information can be transmitted. Payment was remitted in the form of coupons toward Mohawk products!

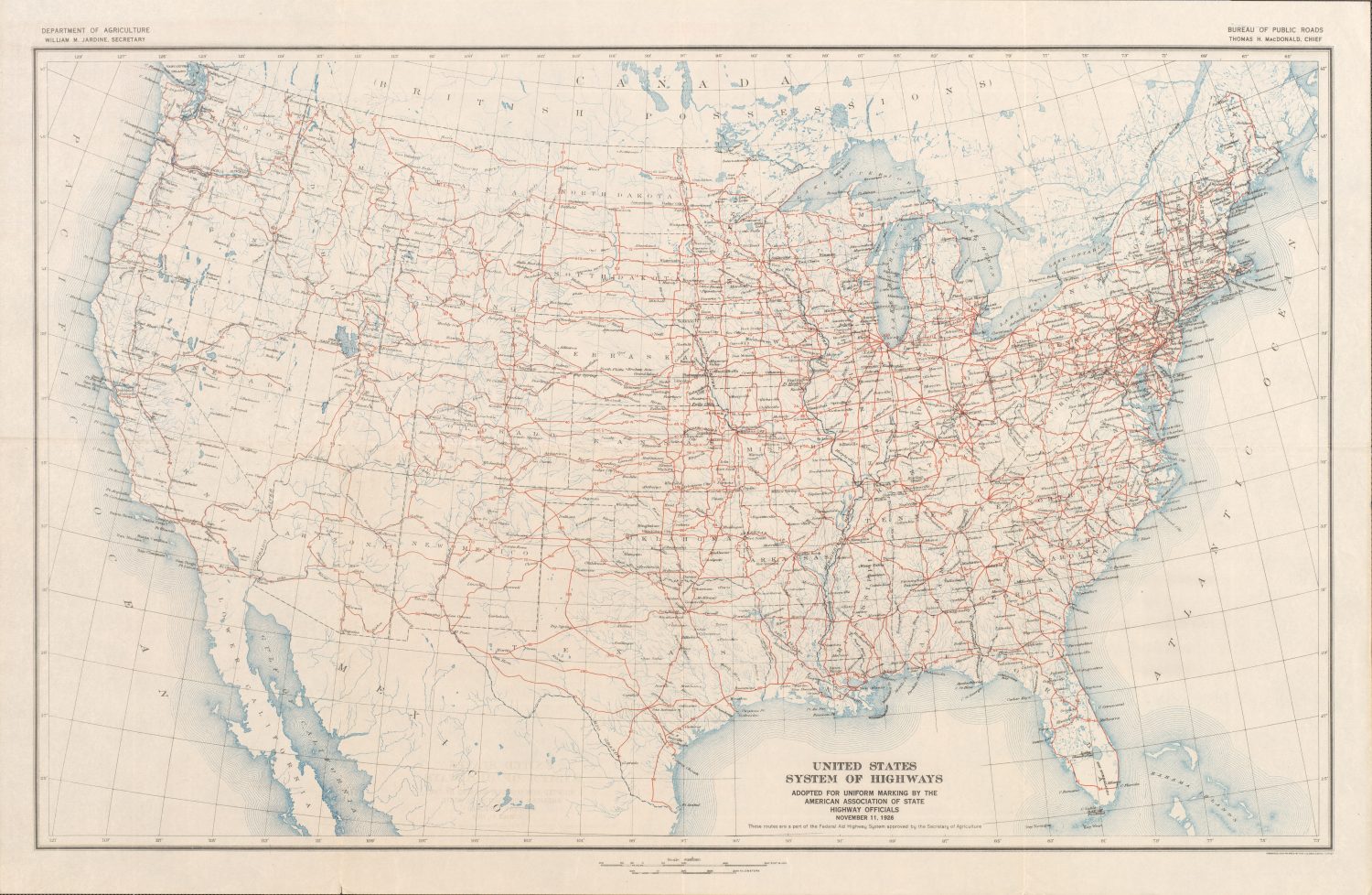

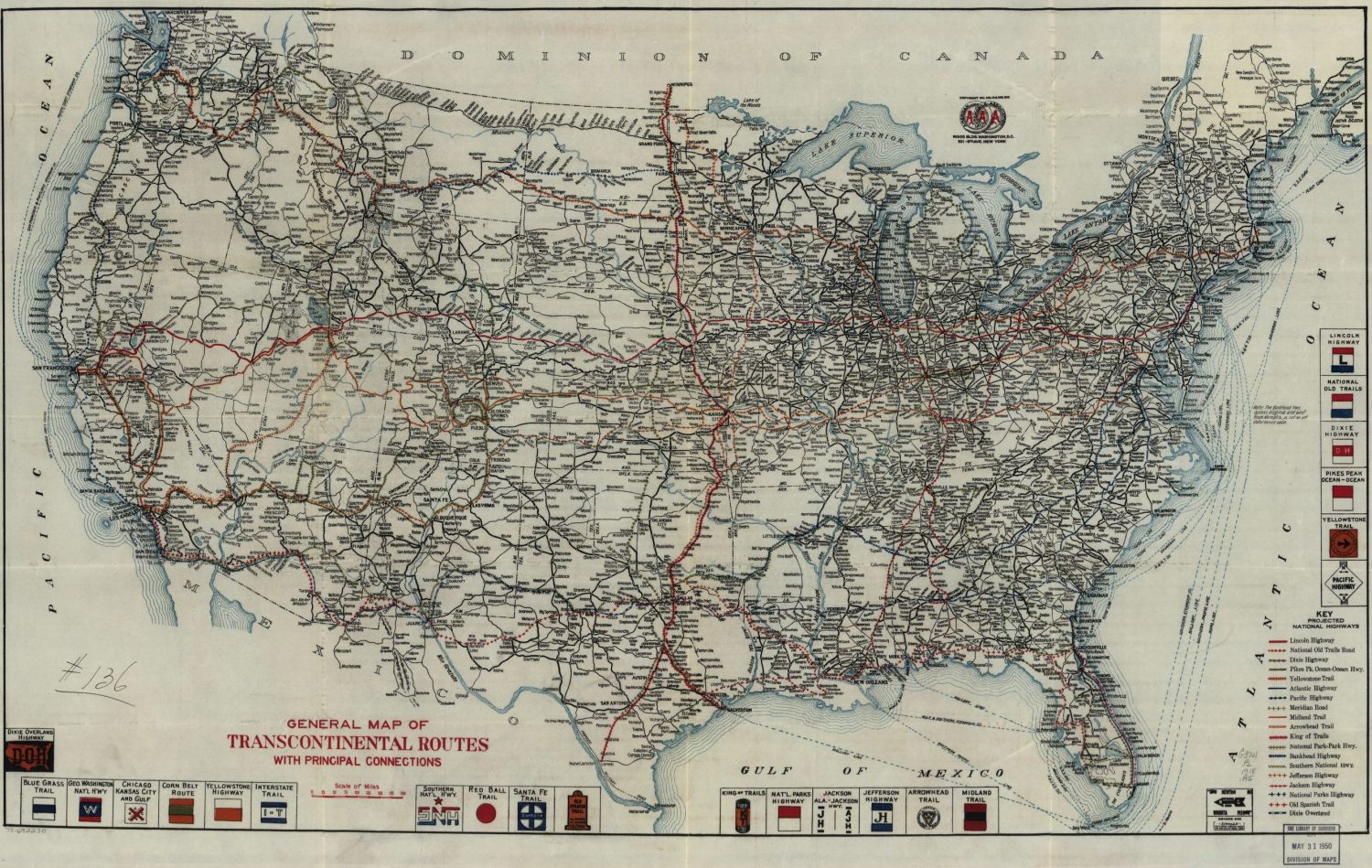

Using these sources, the Mohawk Tourist Service Department was able to regularly update the suggested routes, road conditions, and recommended stops across each edition of the Surface Guide. One major improvement was the incorporation of numbered routes as they began to replace named auto trails. Wisconsin was the first state to embrace the new method in 1918. The entire nation followed suit in 1926 with the adoption of the U.S. Numbered Highway System.

Interestingly, the titles of the guides rarely changed, even as the marked trails were replaced entirely with numbered highways. Only references on the pages were updated.

A few other modest changes took place over the course of the publication history. Prices increased from 15 to 20 cents, the strip maps were improved, the elevation charts were redesigned, and a system of point rankings was adopted for the recommendations.

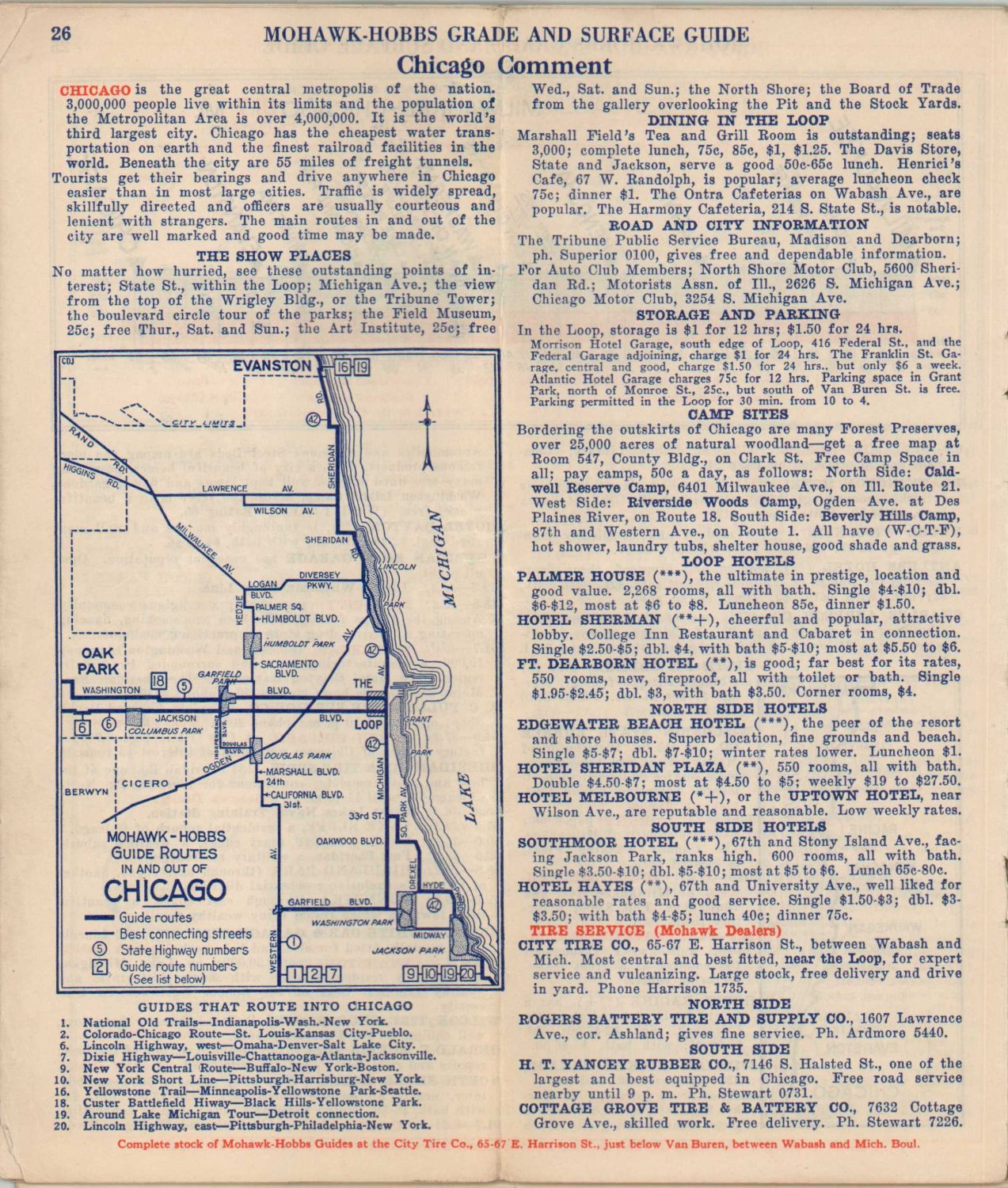

The last page/back panel of each guide is likely most familiar to a modern audience. It shows a map of the regional road system, with the entire length of the respective highway highlighted in red. The inclusion is notable. As the nation’s roads developed and expanded, a distinct cartographic transition took place in which ‘network’ maps replaced earlier strip-style route maps, eventually evolving into the ubiquitous oil maps of the 1950s and later. The Hobbs Grade and Surface Guides are excellent examples of this progression, incorporating earlier travel elements such as the route log and elevation diagram while recognizing the utility of presenting ‘the bigger picture’ made possible by a network map.

Despite the originality of issuing a regularly updated assembly of visual and textual road data, the Mohawk-Hobbs Surface Guides eventually fell out of publication by the early 1930s. Later editions were even sponsored by Mohawk’s rival, B.F. Goodrich! It appears that by 1933, Hobbs sold the rights to his guide to the H.M. Gousha Company, eventually leading to a falling out and lawsuit.

A variety of factors likely contributed to phasing out the guides, apart from the litigation between Hobbs and Gousha. It’s possible the costs and efforts required to obtain accurate information were just too great (especially during the Great Depression), changing travel habits made simpler network maps preferable to motorists, or the utility of such minutiae as elevation diminished as vehicles became more powerful and roads improved.

In any case, the relatively short run of around 11 years provides a fascinating insight into how early auto trails rapidly evolved into a system of national highways after the end of World War I. The network of connected interstate roads constructed during the 1920s and 1930s liberated the average American traveler from the restrictions of railway timetables and ushered in a new period of more democratic motor tourism.

“The road map and the highway space it represented gave driving Americans the tools to explore the national territory in numbers and over distances without parallel in any other nation’s experience. It widened the horizons of average Americans by leading them to and through radically different physical and cultural landscapes from those they knew at home…The automobile journey, guided by the road map, became for many Americans a means of discovering a common national geography, history, and culture.”

[Akerman p. 153]

Sources/Further Reading

- Akerman, J. (2006) “Twentieth-Century American Road Maps and the Making of a National Motorized Space,” in J. Akerman (ed.) Cartographies of travel and Navigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Guinn, Jeff. “The Vagabonds.” The Story of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison’s Ten-Year Road Trip, 2019.

- Harmon, David L. (2001). “American camp culture: A history of recreational vehicle development and leisure camping in the United States, 1890-1960.” Dissertation.

- Hobbs v. Gousha Co., Casetext (Appellate Court of Illinois, First District December 13, 1939). Retrieved from https://casetext.com/case/hobbs-v-gousha-co

- Mark, Stephen. “Save the Auto Camps.” Crater Lake Institute, 26 May 2019, www.craterlakeinstitute.com/index-of-general-cultural-history-books/park-structures/save-the-auto-camps.

- Ristow, Walter W. “American Road Maps and Guides.” The Scientific Monthly, vol. 62, no. 5, 1946, pp. 397–406.

- “Timeline – Contributions and Crossroads: Our National Road System’s Impact on the U.S. Economy and Way of Life (1916- 2016) | Federal Highway Administration.” www.fhwa.dot.gov/candc/timeline.cfm.