I was recently cataloging a 19th-century travel volume described online as a ‘beginner’s guide to the Oregon Trail.’ Having spent many hours playing the PC game at the Knox County Library (usually, not very well), I was immediately intrigued. After reading the book, The Prairie Traveler: A Hand-Book for Overland Expeditions, from cover to cover, I still don’t think I’m prepared to travel west via horse or wagon, but I thought it would be fun to share my thoughts in the same way that Michael shares inspiration in The Office (not very originally). If you’re ready to hit the trail, skip to the end for my Key Takeaways, or go to VisitOregon.com to play the original game for free.

Me, re-packaging Randolph Marcy’s work 165 years later.

The book was written by U.S. Army Captain Randolph B. Marcy (1812-1887) and first published in 1859 (technically, a decade after the starting date of The Oregon Trail). By that time, Marcy had an experienced career as an Army officer. Upon graduating from West Point in 1832, he served in the Black Hawk and Mexican-American Wars. After the latter conflict, Marcy was given command of Fort Towson in the Indian Territory. There, he was charged with protecting the hordes of emigrants heading west to strike it rich in the gold mines of California. He led several expeditions to establish new forts, survey trails, and explore unknown territory, including an uncommonly successful effort to find the source of the Red River. In 1857, Marcy directed a relief column over 1,000 miles to provide winter supplies for Albert Sidney Johnston’s expedition against the Mormons in Utah.

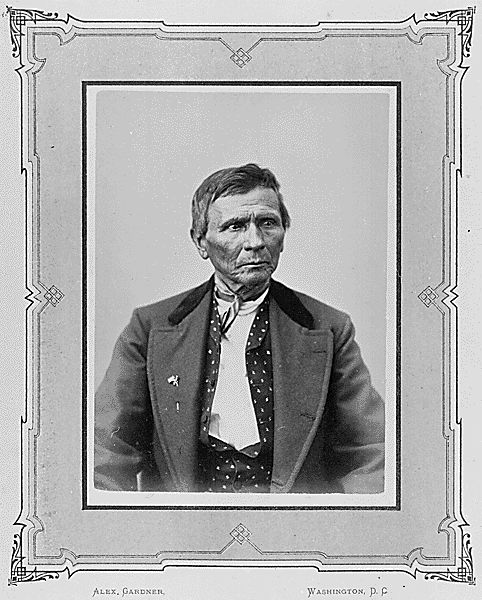

Portrait of Captain Randolph B. Marcy, c. 1870. Courtesy of the Library of Congress (Control #2017893772).

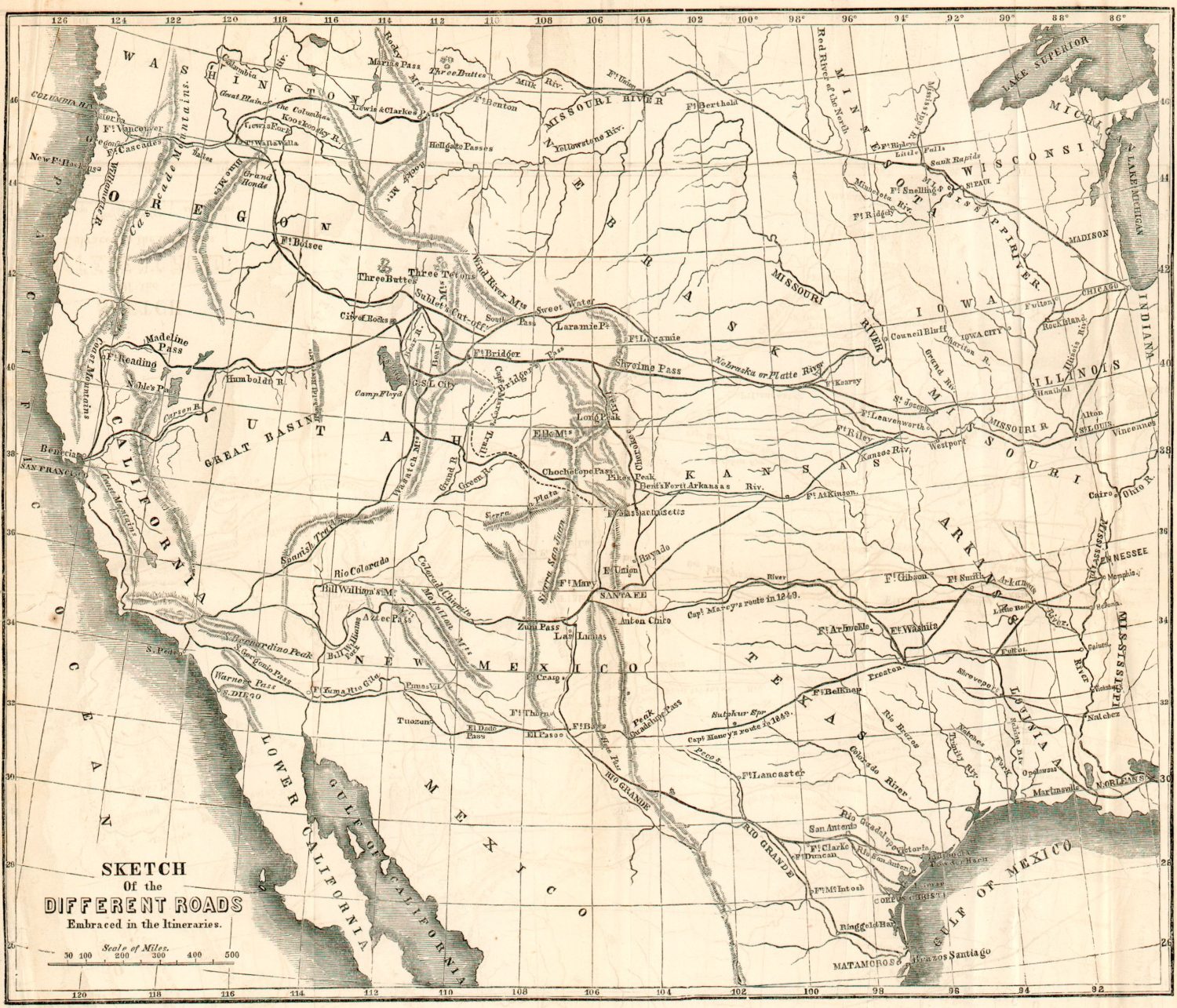

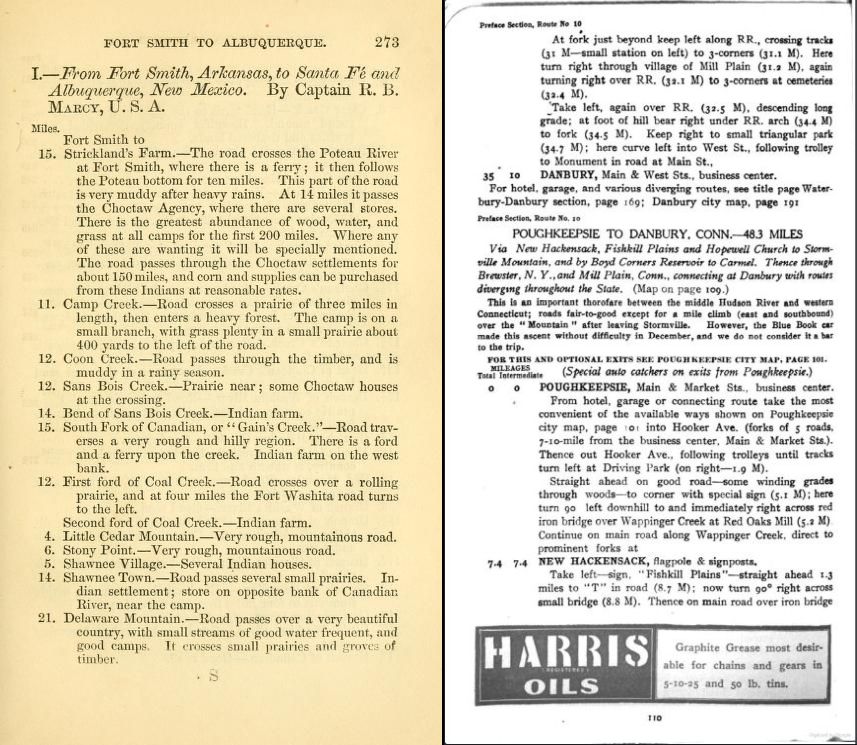

Shortly after this impressive and widely celebrated feat, Captain Marcy was recalled to Washington. The War Department wanted him to utilize his over-quarter century of experience to compile a guidebook for Western voyagers. In addition to serving the public good, it was hoped that the dissemination of sound advice would minimize the need for Army intervention (defense, rescue, etc.). The resulting publication, The Prairie Traveler: A Hand-Book for Overland Expeditions, was an immediate hit. Thousands of copies were carried in saddlebags, stagecoaches, and knapsacks across the vast plains, deserts, and mountains of the American West. The book includes a map, but frankly, it is one of the least practical components and serves only as a basic reference. The real navigational aids come in the form of individual itineraries printed for each suggested route (28 in total). Interestingly, these travel outlines share several characteristics with early automobile road guides.

Marcy’s map labels many of the routes outlined within his volume, as well as the numerous geographic features and natural landmarks along the trail(s). The obstacles posed by mountains and rivers may seem minimal within the image, but the accompanying text makes plain the many dangers. Note Vincennes (my hometown) as the easternmost starting point.

Side-by-side comparison of Marcy’s first suggested itinerary to an Automobile Blue Book road log, published 150 years later.

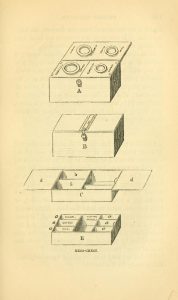

In addition to mileage and directions, The Prairie Traveler provided a wealth of useful information for the intrepid western adventure. The range of content is broad; including recipes for ersatz tobacco, methods for crossing rivers, tips for locating water sources, and warnings on how wood can change with climate. Instructions for a rudimentary water filter, hiding supply caches, basic medical care, and starting a fire are also included. An entire chapter is dedicated to interactions with various Native American tribes – means of communication, fighting tactics, and negotiating strategies are covered in detail.

The table of contents provides a quick overview of the wide variety of topics covered in The Prairie Traveler.

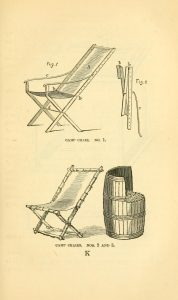

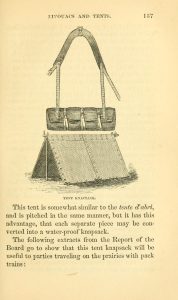

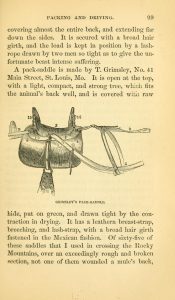

Marcy makes several specific endorsements for particularly helpful items – Grimsley’s Pack Saddle, Van Duzer matches, and a Tent Knapsack are just a few examples. Throughout the volume, the author refers to a wide variety of sources used to supplement his years of expertise. British adventurers, Dutch Boers, French medical experts, and fellow American military officers are quoted and referenced at length.

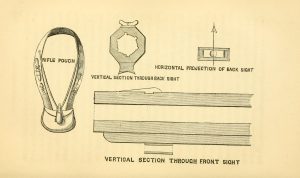

Marcy’s text is accompanied by numerous helpful illustrations that detail recommended products and best practices for life on the trail.

While much of the content is direct and relatively plain-spoken, Marcy interjects several interesting anecdotes throughout his guide. The tragic tale of Billy, a dedicated mule who walked through snow all night to reach camp, is vibrant enough to bring the reader to tears. “Alas! poor Billy! your constancy deserved a better fate; you may, indeed be said to have been a victim to unrequited affection” – pg. 107.

One simple story tells much about steadfast perseverance on the trail:

“I know an instance where one resolute man, pursued for several days by a large party of Comanches on the Santa Fe trace, defended himself by dismounting and pointing his rifle at the foremost whenever they came near him, which always had the effect of turning them back. This was repeated so often that the Indians finally abandoned the pursuit, and left the traveler to pursue his journey without further molestation. During all this time he did not discharge his rifle; had he done so he would doubtless have been killed.” – pg. 56

The universal sign of telling an unwelcome stranger to keep away.

There are also a few instances of humor and amusement.

“Upon one occasion I endeavored to teach a Delaware the use of a compass. He seemed much interested in its mechanism, and very attentively observed the oscillations of the needle…He did not, however, seem to comprehend it in the least, but regarded the entire proceeding as a species of necromantic performance got up for his especial benefit, and I was about putting away the instrument when he motioned me to stop, and came walking toward it with a very serious but incredulous countenance, remarking, as he pointed his finger toward it, “Maybe he tell lie sometime.”

The ignorance evinced by this Indian regarding the uses of the compass is less remarkable than that of some white men who are occasionally met upon the frontier.” – pg. 186

But it wasn’t just his impressive military career, helpful tips, and engaging writing style that is worth highlighting. Marcy seemed like a relatively modern man for the ‘Wild West’. His rich array of quoted sources reflects an active mind and diverse interests. Good sanitation practices (notably regarding water) and practical safety measures are emphasized in several sections throughout The Prairie Traveler. He constantly warns against the abuse of animals and laments the wanton destruction of wildlife, especially large herds of deer and buffalo that were once common on the Plains. When discussing the latter;

“It provides food, clothing, and shelter to thousands of natives whose means of livelihood depend almost exclusively upon this gigantic monarch of the prairies. Not many years since they thronged in countless multitudes all over that vast area lying between Mexico and the British possessions, but now their range is confined within very narrow limits, and a few more years will probably witness the extinction of the species.” pg. 234

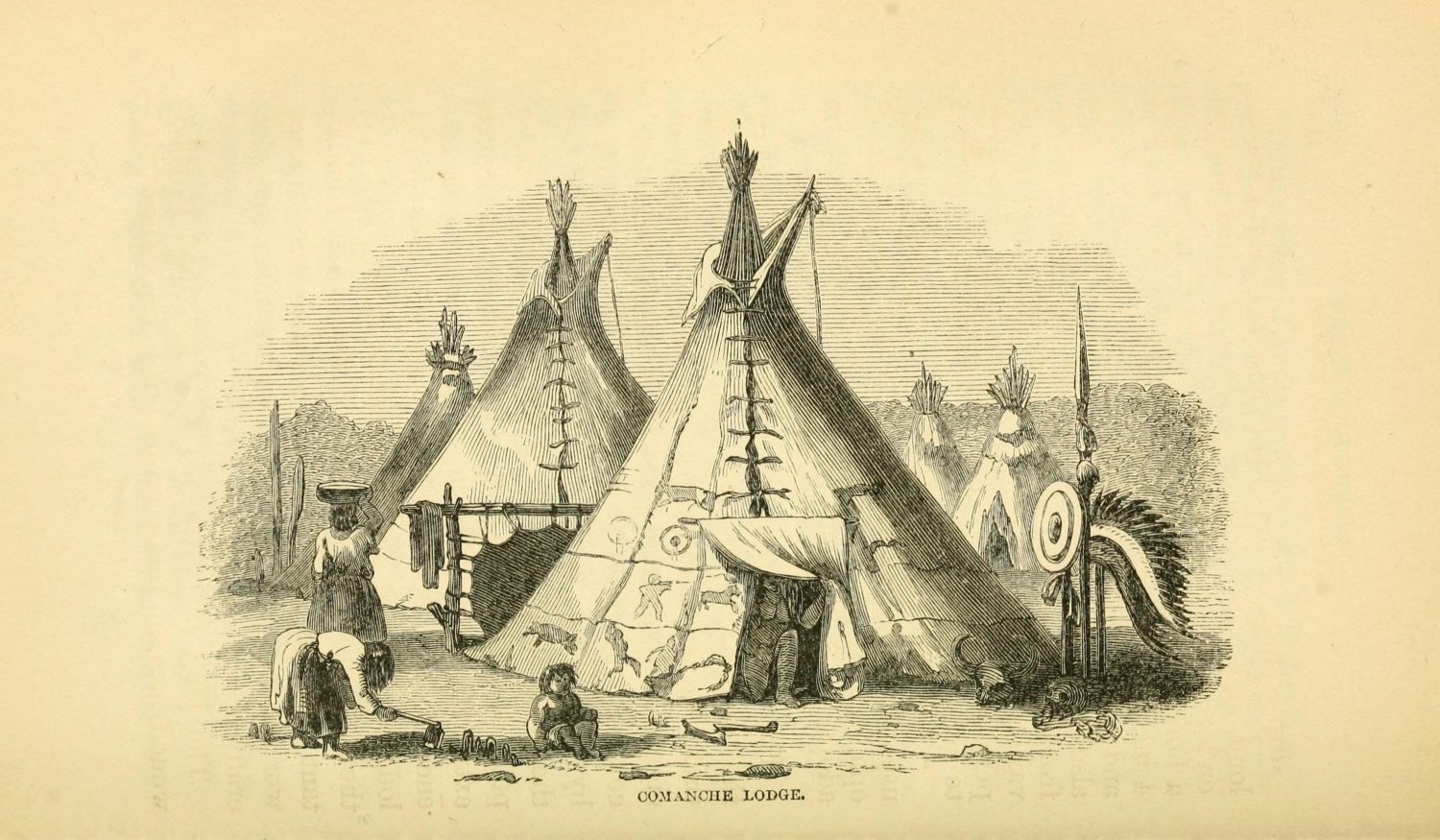

Marcy’s views on Native Americans are nuanced and should be interpreted with an understanding of general contemporary racial attitudes. The overall organization of the book is emblematic – ‘uncivilized’ tribes of the West are discussed separately and at much greater length than those elsewhere. His wartime actions against Indigenous peoples are manifest, but appear to be consistent with the rules of engagement and not driven by hatred. He is occasionally critical of a lack of ‘honor’ in combat and business dealings. The word savage is used, though sparsely, but broad generalizations are made about the dispositions of various tribes. One notable example reads, “They [Delaware tribe] are among the Indians as the Jews among the whites, essentially wanderers” (pg. 185).

Illustration of the types of dwellings used on the plains by the nomadic Comanche.

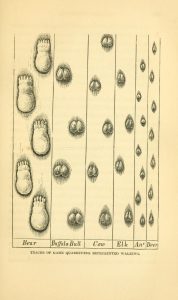

However, there is a clear appreciation for aspects of Indigenous culture, environmental skills, and martial interests. Speaking from personal experience, he recalls an instance where he mistook a bear track for the result of grass blowing in the wind. “The truth of this explanation was apparent, yet it occurred to me that its solution would have baffled the wits of most white men” (pg 175). The use of diplomacy when engaging with Native American tribes is encouraged. Much attention is given to the experience and wisdom of Marcy’s close friend, Black Beaver – the subject of an entire chapter.

A portrait of Black Beaver, a Delaware scout and interpreter, courtesy of the National Archives (Control # NWDNS-75-ID-118A)

While it’s impossible to conclusively determine Marcy’s convictions from this one work alone, The Prairie Traveler was indeed a product of its time. This is especially evident in the medical field, with the tacit support of the miasma theory and several questionable remedies, including getting drunk to treat a rattlesnake bite. Another notable example refers to the alleged process by which bighorn sheep quickly descend the mountainous landscape – by sliding down on their horns! (pg. 251)

“Of all the remedies known to me, I should decidedly prefer ardent spirits. It is considered a sovereign antidote among our Western frontier settlers, and I would make use of it with great confidence. It must be taken until the patient becomes very much intoxicated, and this requires a large quantity, as the action of the poison seems to counteract its effects.” – pg. 129

These folksy inclusions are part of the reason the volume remains an entertaining read to this day. It was also very popular when it was issued. Emigrants, cowboys, gold-seekers, and businessmen would have all found subjects of interest between the covers. The first edition, published in New York by Harper & Brothers in 1859, sold quite quickly, prompting official reprints in 1860, 1861, and 1863. The last edition, edited by the famed Richard Burton, featured significant updates from his recent trip to the Great Salt Lake.

Title page from the 1863 edition of The Prairie Traveler, published in London.

Starting in 1863, Marcy served as the official inspector for several different departments of the U.S. Army, until his promotion to Brigadier General and Inspector General in 1878. He would retire from his long career in 1881 before passing away six years later. Throughout his almost five decades in the Army, Marcy would have seen a dramatic change in the landscape of the western United States. The expansion of ‘civilization’ and the growth of the nationwide rail network gradually eroded the danger and uncertainty of Western travel. While the absolute relevancy of The Prairie Traveler may have been limited to only 10 – 20 years, it remains an important document that captures well the 19th-century American ‘pre-modern’ attitudes regarding Manifest Destiny.

Check it out for yourself for free online or in eBook format at Project Gutenberg!

Key Takeaways for the Oregon Trail (Not Personally Tested)

- You’ll need about 2 lbs. of provisions per person, per day. Desiccated vegetables, dried soup, parched corn, and bacon are good options.

- Don’t overpack and leave the luxuries at home.

- Treat your animals well. Don’t overwork (especially in the early weeks of the trip) or abuse, and put in the extra effort to search for adequate forage. During popular travel periods, this can be a serious challenge.

- Try to cover approximately 15 – 18 miles per day with a wagon train, but you can go 30 miles or more per day using only pack animals.

- Travel armed. Marcy recommends the Colt Army Revolver (more stopping power than the Navy counterpart) and discusses the pros and cons of several long guns. A good knife is also a must.

- Do not forget an awl! It can be used in conjunction with buckskin or buffalo hide to repair everything from moccasins to wagon covers.

- Exercising caution and encouraging teamwork are keys to survival and success. Accidents can be deadly on the trail.

- Mules make good pickets! Bell-mares should be used, where applicable.

- Bring cash, if you can spare it. Trading posts and entrepreneurs along the way will allow for basic resupply, new animals, etc.

Sources/Further Reading

- Thirty Years of Army Life on the Border by Randolph Marcy(New York: Harper & Brothers, 1866). Scanned at the Library of Congress.

- Beyond Cross Timbers by W. Eugene Hollon (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1955)

- Biography at Texas State Historical Society

- Biography at Oklahoma Historical Society

- Fully scanned copy at the Library of Congress

- The Kansas Collection

- Wagner & Camp (The Plains and the Rockies) #335

- Play Oregon Trail free online at VisitOregon.com

A view of Fort Smith, Arkansas; an important frontier military post, stop along the Butterfield Overland Mail route, and point of strength for enforcement of the Trail of Tears.