On the night of October 8, 1871, a small fire broke out in Chicago’s Near West Side, at the site of today’s CFD Quinn Fire Academy. (Though you may have heard something about Mrs. O’Leary’s cow knocking over a lantern, this isn’t totally true. The reporter later admitted to making that part up, though the fire did start somewhere close to the barn).

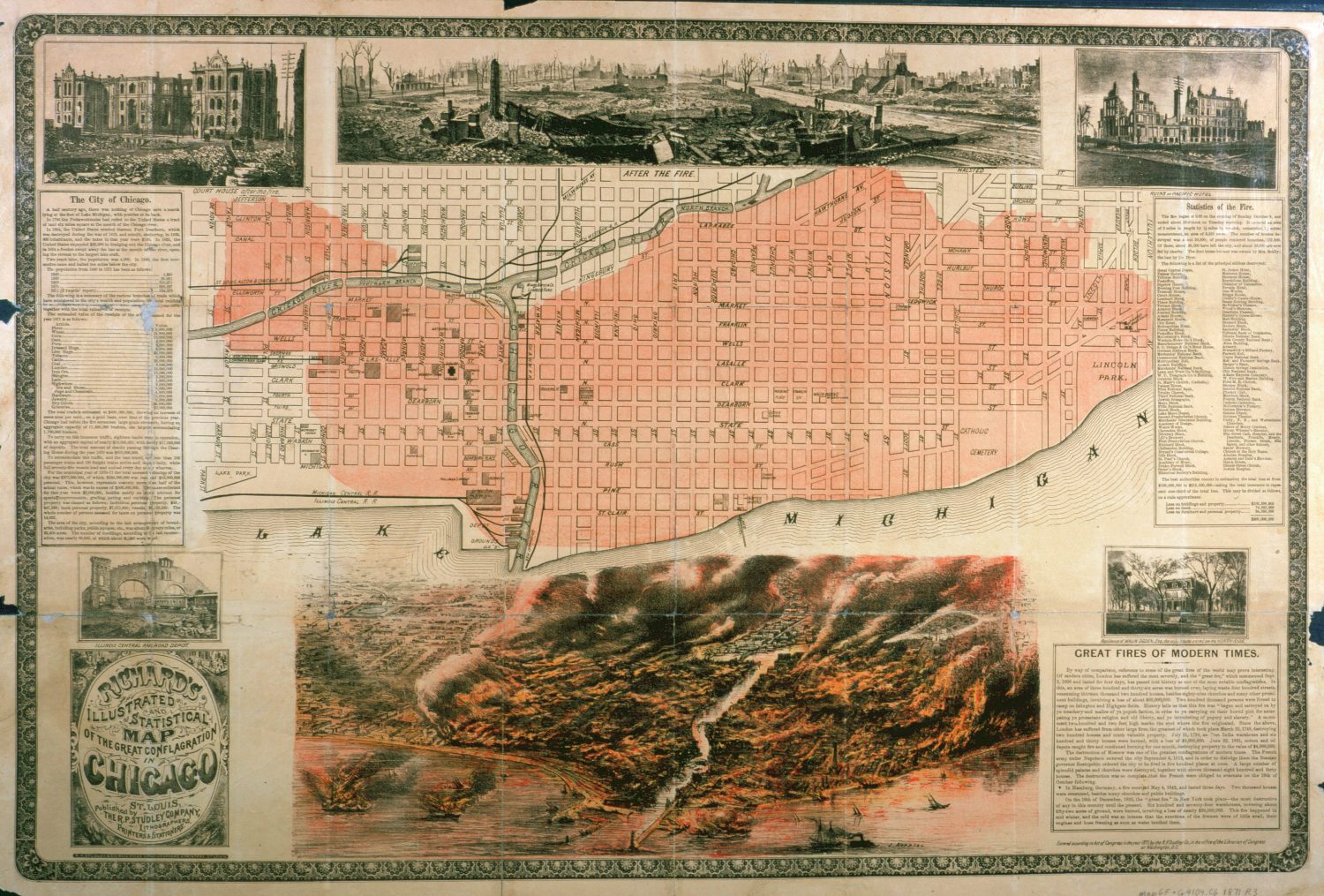

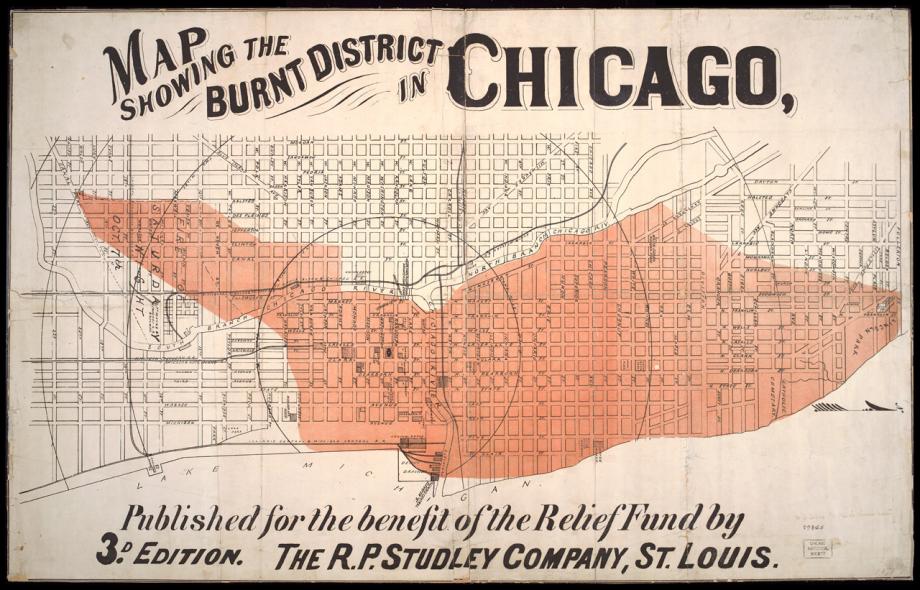

The real fault in the catastrophe lay with the conditions – an exceptionally dry summer, strong winds, inexpensive wood frame construction and practically no fire codes whatsoever. The blaze quickly grew into a northbound inferno, whose sparks leapt over the river twice to combustible material on the opposite banks. By the time a light rain started to fall on the night of October 9th, over 3 square miles of the city had burned to the ground.

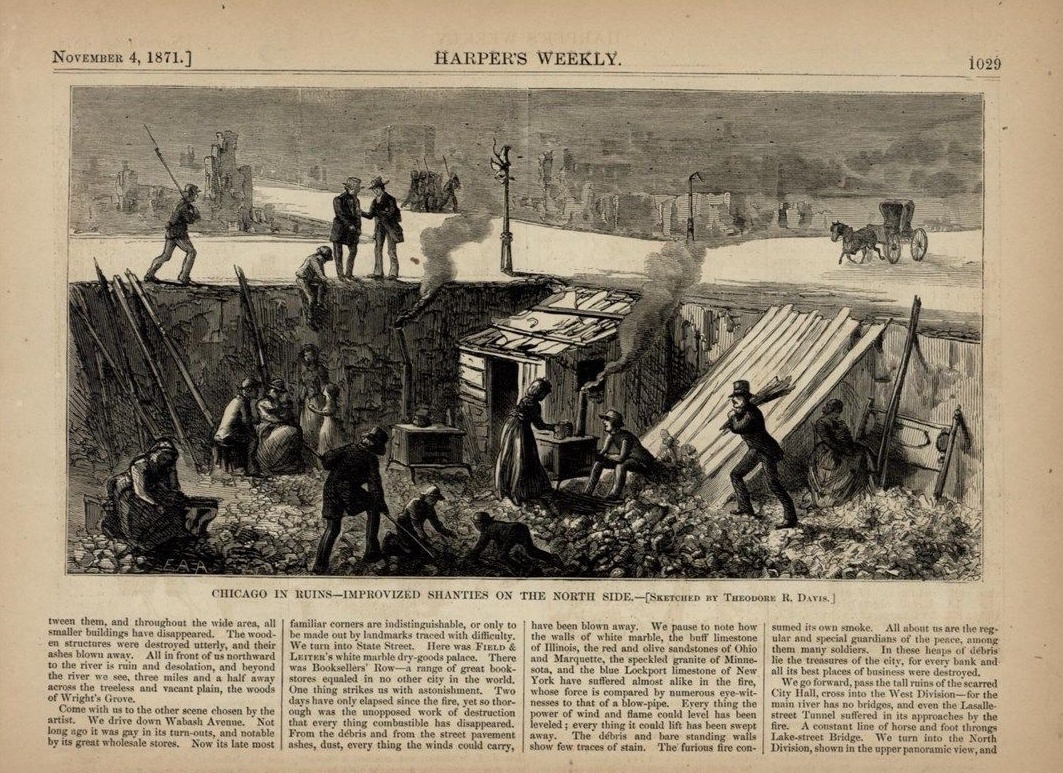

The tremendous destruction can be quantified any number of ways – an estimated 300 deaths, 100,000+ homeless, $200+ million in damage, thousands of buildings, including the city’s impressive courthouse and the new Palmer House hotel, lost forever. To combat looting, General Philip Sheridan arrived on October 11 and put the city under martial law.

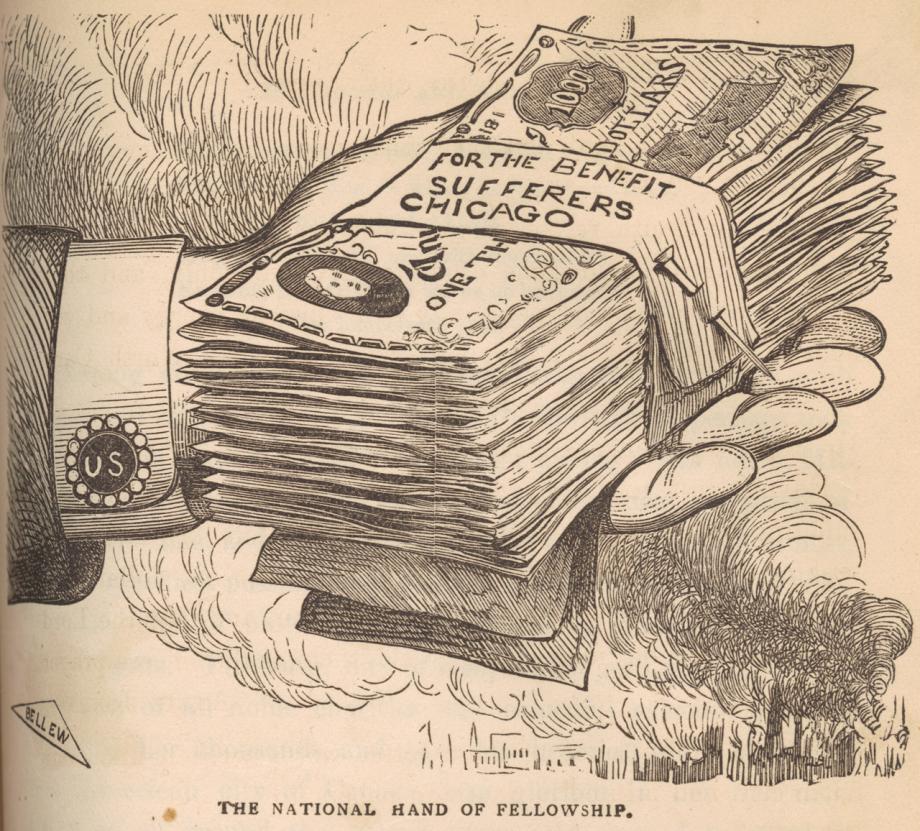

Despite the devastation, much of the city’s infrastructure remained untouched; wharves, warehouses and grain elevators were quickly bustling with relief activity thanks to the readily available transportation network and central geographic location. Donations flooded in from around the globe, and public and private institutions quickly organized to facilitate temporary shelter, food distribution, and free entertainment.

The story of Chicago’s incredible reconstruction is one that generally credits local enthusiasm and a healthy dose of capitalism as the primary motivators. But the rapidity with which rubble was cleared away (pushed into the lake for more prime real estate) and the profound re-shuffling of the city’s poor (pushed into ethnically-centered neighborhoods in the outskirts) leads me to think that it was grief, rather than hope, that saw a city so quickly rise from the ashes.

In the years immediately following the fire, labor unrest skyrocketed due to construction demands outpacing worker safety. Rents rose unchecked. Dozens of insurance companies failed, which disproportionately affected small businesses and individuals who could not afford the high premiums to operate within the city. Political favoritism, naturally favoring the rich and well-connected, was rampant.

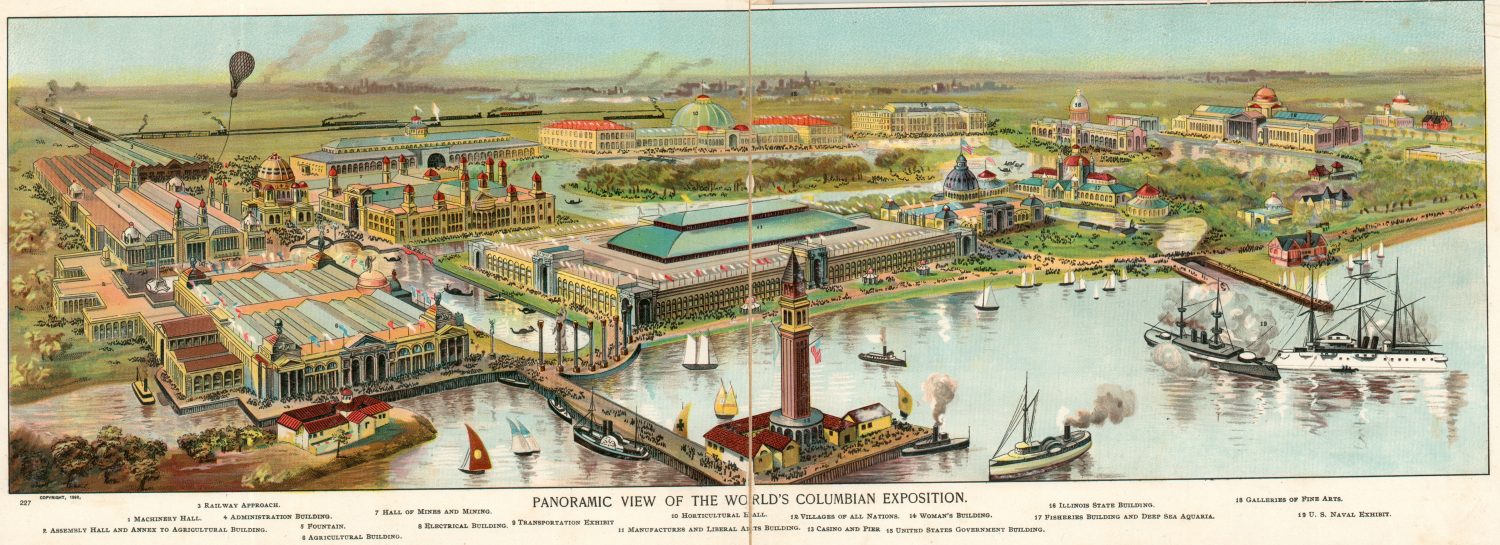

But those looking to make it in the Windy City could likely not dwell on such considerations for long. Outsiders were coming in droves, and the city’s population grew by nearly double in the two decades immediately after the fire. An influx of capital and new steel frame construction techniques led to the development of a revolutionary building design – the skyscraper (named after the topmost sail on a ship). Chicago’s resurrection culminated in the grandiose Columbian Exposition of 1893, one of the most iconic events that took place in all of the 19th century.

The importance of these related events to the city’s history is such that they are represented by two of the four stars on the official flag. But the glamorization of the fire and the rebuilding of Chicago distracts from the contemporary realities – devastating fires in the 19th century were not uncommon (coincidentally, the deadliest fire in American history started on the same day near Peshtigo, WI 250 miles north), events disproportionately affected the poorer classes, and reconstruction efforts were hampered by greed and special interests. Even the story of how the fire started immediately became politicized as a vindictive narrative against the local Irish population – poor Mrs. O’Leary and her innocent cow.

For more information, check out the Chicago History Museum’s website here.

The story of Chicago’s Great Fire is well documented, and numerous maps, prints, and books were issued in the immediate aftermath. (There is even one apocryphal story of a local printer burying his plates on the shores of Lake Michigan to save them from the blaze). I have a number of items in stock related to the event, which can be found here.

References:

Colbert, E. (1871). Chicago and the great conflagration! Chicago.

Miller, D., 2014. City Of The Century. New York: RosettaBooks.